Analysts of foreign policy and diplomacy typically focus on events that occur over a limited period of time to draw conclusions about the nature of relations between states. But in the case of Sino-Nepal relations, if we take a much longer time period to discuss some of its intricacies, we are afforded with a unique historic perspective on developments of the contemporary period.

Beginning with the introduction of Buddhism from Nepal to China right up to the launch this week of a

Chinese weekly newspaper in Nepal, it is an exceptionally long legacy that constitutes the association between these two states. The notion of ‘tripartite relations’ involving China, India

and Nepal, for instance, is not new.

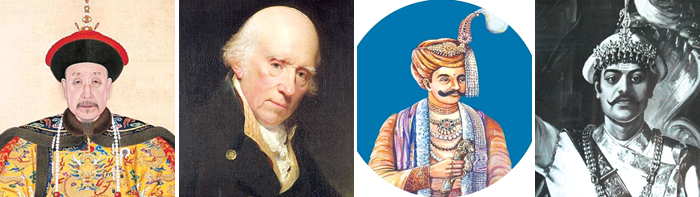

GEOPOLITICAL HISTORY: Nepal was always a 'middle kingdom' since the time of (left to right) Chinese Emperor Qianlong, British Governor General Warren Hastings, King Harshavardana in northern India and King Prithvi Narayan Shah.

In 1770, the first Governor-General of Bengal, Warren Hastings, dispatched an emissary to Nepal to put forward a proposal to Jaya Prakash Malla of Kathmandu and Pritivi Narayan Shah of Gorkha seeking their cooperation to assist the East India Company to establish a direct channel of communication with Peking.

The British at the time were facing problems in commerce in the port of Canton from what they termed ‘narrow-minded local officials’ and felt that if ‘they could present their complaints directly to Peking many of their problems would be solved’. Though the conditions were different, there was a precursor for trilateral cooperation nearly 250 years ago.

Sino-Nepal relations were also ‘global’ in nature. The Marquis Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805), a leading British general in the American War of Independence used to be Governor-General of India and received complaints from the Court of Peking about encroachments by the ‘Government of Nepaul’ upon territories under Chinese jurisdiction and so therefore had come to the ‘resolution of chastising the aggressor, or the Robber’ as the king of Nepal was?described in the dispatches.

China and Nepal went to war in 1791-1792, the last battle of which was fought near the Betrawadi River, a mere 20 km north of Kathmandu. Sitting in Calcutta, Cornwallis had procrastinated on requests for assistance from both sides during the hostilities, but decided eventually that ‘the commercial advantages that Bengal may obtain by a friendly and open intercourse with both countries [made it] no less political than humane in us to interfere our good offices and endeavor to reestablish peace’.

However, the envoy that Cornwallis had selected to mediate, Col William Kirkpatrick, was in Patna en route to Kathmandu when he discovered that the ‘Nepaul Regency', either dubious of the efficacy of our interposition with the Chinese, or fearful of the influence which, if successful, it might give us in their future councils, had suddenly, and without any reference to the British Government, concluded such a treaty with the invaders, as entirely superseded the necessity of the proposed mediation’.

Ironically, this peace agreement signed on 30 September 1792 between Kaji Dev Dutta Thapa and General Fu K’ang-an stipulated and introduced the quinquennial mission system (five-yearly Nepali missions?to the Peking Court) that lasted more than a century till 1906 and laid the foundations for an unprecedented and sustained interaction between China and Nepal.

The ties were remarkably stable in spite of the changes in leadership in both countries during this period with six emperors, five kings and seven prime ministers in the two countries. Perhaps it is based on this historical memory that China today does not maintain rigid fraternal relations with any specific political element in Nepal, rather engaging as it does with whoever occupies the seat of power which is essentially a reflection of the will of the people.

Triangular trade between China and India via Nepal goes back even further, to the period of Princess Bhrikuti in the 7th century. The matrimonial alliance had the effect not only of opening Nepal to the outside world, it also facilitated communication between China and India by opening a new and more efficient route across the Himalaya at Kerung Pass.

This new route between Lhasa and Kathmandu was first used by an official Chinese mission to Nepal commanded by army officer Li Piao and 22 others, who proceeded on to the Court of King Harshavardhana of India, a convert and great patron of Buddhism then ruling over the entire Indo-Gangetic plain north of the Narmada River.

Li Piao’s delegation was received in Kathmandu by King Narendra Deva who took pleasure in showing his guests around, even escorting them to ‘the south-east of the capital [where] there is a lake full of water and of flame. The water does not flow but it always boils. If one holds a lighted candle by hand, the whole of the lake is set on fire; the fume and flame rise upward to several feet’. It was believed that in the bed of this lake was embedded the crown of Maitreya Buddha.

This Chinese awe at the mysticism and exotica of Nepal has carried through to this day and is what draws increasing numbers of Chinese tourists to Nepal.?It is also the legacy of a shared history that sustains Nepal’s ties with China.

Bhaskar Koirala is a PhD student at the School of International Studies, Peking University and also director of the Nepal Institute of International and Strategic Studies

www.niiss.org.np

Read also:

Trilateral Track Two