Empowering the grassroots institutions must be the legacy of technocrat budget framers

It has become a ritual as the

budget is again around the corner that interactions and discussions are organised across town to discuss priorities. The only difference this time is that it is a technocratic election government that is doing the planning.

In one of the discussions, bureaucrat Finance Minister Shankar Koirala said the government budget is basically a ‘political’ document. What did he mean?

The current non-political government, composed entirely of former officials, faces a moral and professional imperative to show that it is different. Most previous budgets have suffered from three fundamental deficiencies.

First, while they have all been made to sound right in terms of numbers and principles, they were invariably tampered with by the party in power by hiding allocations to serve their own party or personal interests. The expanded grant allocations to the VDCs initially made by the UML in mid-90s in the name of so-called ‘Build Your Own Village Yourself’ campaign is one such notorious example.

PICS: NACRMPL (left),MARTY LOGAN (right)

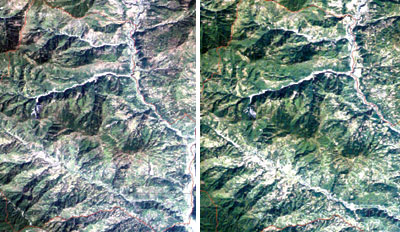

ROOT CAUSE: Under local grassroots initiatives in community forest management, these hills in Sindhupalchok went from arid (pic left, taken in 1978) to evergreen (pic right, taken in 2006).

SDC

Pic left was taken in 1975 and pic right in 2005.

Since the allocation was not backed by any serious programming or policy provisions, it was clearly designed to buy votes in the next election. But it turned out to be a one-way traffic. All governments that followed only continued to embellish these grants year after year. Politicians of all hues colluded with local officials to partake of the spoils.

Second, most finance ministers with their penchant for populism, promise just about everything under the sun in budget speeches only to forget them after its passage. In post-1990 Nepal, the first prime minister to resort to such deceit was GP Koirala whose government then promised that “the absolute poor will be identified and preference will be given to them in government-run projects”. The promise was about job reservation for the poor. Had that promise been implemented, Nepal today would be on a different growth path benefitting from the demographic dividend. Instead, that dividend is being appropriated by other countries which use our workforce.

Third, corruption just got a further boost at the hands of this ‘non-political’ government which appointed the celebrated

Lok Man Singh Karki to the high office of CIAA chief at the recommendation of none other than the four party syndicate which has become synonymous with corruption and extortion.

HELVETAS

A landsat image of the same area in Sindhupalchok charting the progress made from 1990 to 2010.

So whatever the laudable principles that are enunciated in the budget speeches, the resources allocated remain subject to cuts at various levels at the hands of politicians themselves and the colluding officials and contractors protected and promoted by them.

Pakistan’s experience with a technocrat government 15 years ago may be useful to remember. A neutral non-political government under Moeen Qureshi, a World Bank vice-president, was installed to conduct elections. Within just a few months it became so popular that there was nationwide clamour for it to continue indefinitely. Being unencumbered by excess baggage of unholy political loyalties, a non-party government can accomplish much as long as it is guided by professionalism and integrity.

Despite poor governance, Nepal has made its mark in two areas. Firstly, we are an acknowledged world leader in community management of natural resources because of the dramatic restoration of our forest wealth through the nationwide network of forest user groups. Nepal is also at the top of the table in world ranking in meeting the

MDGs in child survival and maternal mortality rate reduction.

These achievements were possible due to the nationwide network of mothers’ groups and their female community health volunteers. While these grassroots institutions were innovated in 1988 during the Panchayat, they continued to grow during the post-1990 years because they were owned and managed by the users themselves.

But the tragedy is that despite such pioneering work and extraordinary successes, no multiparty government in the last quarter century ever thought of extending it to other sectors of community-led development. This is where the present government could make a difference through the upcoming budget.

By all indications, if grassroots empowerment could encompass all development sectors in the communities, then our rural landscape would steadily transform for the better even when the politicians continue their corrupt ways. Finance minister Koirala must see the upcoming annual budget as a political document only in the sense that it empowers people at the grassroots in this predominantly rural country.

Bihari Krishna Shrestha is an anthropologist and was a senior official in the government.

Read also

Distant normalisation

On a tight budget