The proportion of women who smoke in Nepal is higher than most countries in the region

It’s 9AM in Ratna Park. Street vendors have neatly laid out packets of cigarettes, chewing tobacco, and beetle nuts on the sidewalk. A group of men puffs away, discussing politics. At the microbus stand, drivers gesture to passengers with one hand and drag on a cigarette with the other.

Almost two years after the government introduced the Tobacco Product Control and Regulatory Bill, it finally banned smoking in public places including offices, schools, libraries, airports, public lavatories, cinema halls, hotels, restaurants, buses, and even in the sports stadium in August last year. If caught, smokers are fined Rs 100 and repeat offenders have to dole out up to Rs 100,000.

“I know we are not supposed to smoke in public, but I’ve already lit my cigarette, I will smoke with one hand and drive with the other,” says a microbus driver as he blows out a puff of smoke, “I’ve heard people are being fined, but I can’t stop smoking, what can I do?”

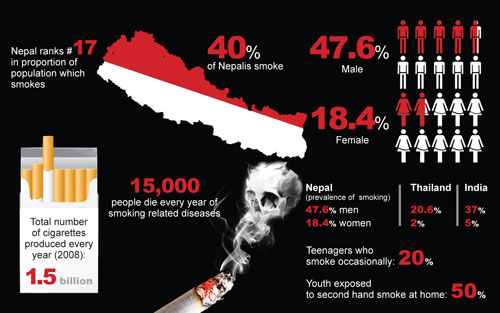

SOURCE: WORLD BANK AND WHO DATA, INFOGRAPHIC: BILASH RAI

The Bill requires cigarette and tobacco companies to cover 75 per cent of the packet or box and print a public health message in Nepali on the back accompanied by a colour image of the effects of tobacco consumption. Advertisement of products and sponsorship of programs in the media by tobacco companies have been prohibited as well. Owners of tobacco industry, however, have filed a case in the Supreme Court against these two clauses and both remain in limbo.

“Yes, smokers are at risk of cancer and respiratory problems like asthma and bronchitis, but these numbers fail to tell us the damage caused to passive smokers,” explains cancer specialist Arti Shah.

Until the bill was introduced, regulation and control were almost non-existent and even a 10-year-old child could buy cigarettes or chewing tobacco from the corner shop. The government had hoped to lessen exposure to second-hand smoking, stem the astonishing rate of lung cancer, and boost life expectancy of Nepalis, yet its commitment towards enforcing the bill is questionable.

“The government banned smoking in public, but I don’t understand why street vendors are still allowed to sell cigarettes freely in the open. It should outlaw the sale of cigarettes in public as well, otherwise people won’t follow this new rule,” a father who was smoking while waiting for a bus at Ratna Park with a toddler in tow told Nepali Times. “If they sell outside, we will smoke outside.”

Initially, the police caught hundreds of offenders, but like most other issues in Nepal, the ban seems to have fallen off the police’s priority list. Kathmandu CDO Chuda Mani Sharma admits the government’s focus at the moment is to make the public more aware and stricter enforcement will follow in the coming months.

Praveen Mishra, secretary at the Ministry of Health and Population, who currently heads a committee to tighten regulations, says: “We can’t achieve 100 per cent success within a few days, it’s a long process. At least Nepalis now have an understanding that there will be rules to control smoking and tobacco consumption in public. Putting the bill into action is our next step.”

Jyoti Baniya, general secretary of the Consumers’ Rights Protection Forum, however, blames the tobacco industry lobby for bullying and not letting the authorities execute the act properly. He says: “The tobacco industry in Nepal is pretty powerful, so unless there is strong political will, business owners will continue to arm twist the state and the bill will only remain on paper.”

See also:

Puffing away

Should We Ban Cigarettes?

Killing you softly

Even you give up smoking in Kathmandu, the choking air

pollution is the equivalent to smoking two packs a day. Doctors say the risk of lung cancer is 20 per cent greater for those living in polluted cities like Beijing, Mexico City or Kathmandu. Add smoking to this and you are liable to stop breathing very soon.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), over a quarter of Nepal’s 26 million people smoke regularly. The number is much higher for those who have ever smoked. Interestingly, Nepal has a much higher rate of smoking among women (18 per cent) than neighbouring India (five per cent) or Thailand (2.1 per cent). The consumption of chewing tobacco is equally rampant, especially among men, with almost one-fifth using khaini.

Smoking has been linked to an increased risk in a number of diseases including lung and throat cancers, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and stroke. Although thought to be less harmful than cigarettes, chewing tobacco can also lead to throat and mouth cancers. Tobacco use is the single biggest cause of preventable death in the world, whether smoked or consumed orally. A Nepali dies every half-an-hour due to smoking-related ailments.

Rubika Waiba, a physician at Capital Hospital in Putali Sadak says: “I have seen a steep rise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchial asthma.”She attributes this to smoking combined with pollution and dust in the city air.

One of the most effective ways to curb tobacco abuse is by limiting or outright banning of advertisement of cigarettes and other products. As a signatory of the WHO Framework Convention for Tobacco Control in 2006, Nepal has tried to enact bans through the Supreme Court verdicts in 2006 and 2009 and also an Executive Order in 2010.

A more comprehensive policy was introduced through the Tobacco Product Control and Regulatory Bill in 2010. The bill proposed a complete ban on smoking in public places and workplaces, ban on cigarette advertisements, and made it mandatory for tobacco companies to cover 75 per cent of cigarette packets or other tobacco products with health warnings.

With 1.5 billion cigarettes produced annually, the tobacco industry in Nepal is a big provider of jobs and some argue that targeting it will only hurt the economy and make thousands unemployed. In the long-term, however, reducing morbidity and mortality by discouraging smoking may turn out to be better for Nepal’s economy.

Can the police do to smoking in public places what it did to drinking and driving?

Sulaiman Daud