Eating and defecation. Activities so vital to our everyday lives, but which we take for granted. We don’t think about them much, so we turn over the pages with coverage of charpis or chulos.

No one cares much whether this country grows enough food or not, whether farmers get proper prices for their products, what happens when children don’t get enough calories at a young age, or how Nepali mothers spend their entire lives gathering firewood and cooking for their families next to smoky stoves.

The media doesn’t care much either about open defecation, hand-washing, diarrhoeal dehydration, separate toilets for girls in school. These subjects are too distasteful to write about, we hacks would rather focus on important subjects like the debate about whether or not elections will be held in November.

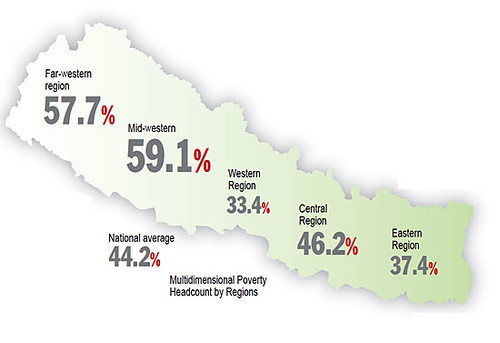

SOURCE: OPHI

Yet, these are matters of life or death for most Nepalis. Eighty per cent of Nepali mothers (they are almost always women) cook with biomass: firewood, straw or dung. In remote mountain villages, indoor smoke from the hearth is a major killer of children. If it’s not acute respiratory infection and pneumonia, come summer children die from diarrhoeal dehydration or cholera because water sources are contaminated by open defecation.

On World Water Day]on 22 March, we carried a story that pointed out the glaring fact that only 40 per cent of schools in Nepal had toilets and only one-fourth of those schools had separate facilities for girl students. Only one-third of the population washed hands after defecation and only 14 per cent of them with soap.

The media isn’t really bothered much that the government is now on a toilet-building spree and districts are competing with each other to declare themselves open-defecation free. Already women in villages are refusing to marry into families that don’t have toilets. Catalysed by donors, water, hygiene and sanitation campaigns have now moved beyond being just an NGO project. It is a social movement which doesn’t need money as much as a change in mindset and awareness about how little it takes to save lives. When communities are empowered, they don’t need a donor-funded project. They need ideas and affordable solutions.

Last week we carried a story from Dadeldhura in far-western Nepal where mothers have seen the benefit of improved smokeless stoves that have become so popular, metal workshops can’t manufacture the chulos fast enough. The stoves cost Rs 400, but they can reduce a mother’s daily workload by more than half because they use half the fuel wood, cook twice as fast, and pots and pans don’t get as dirty. The women and children don’t suffer chronic eye infection anymore and the incidence of pneumonia has dropped dramatically.

There are many small-is-beautiful initiatives like these that have tested well at a local level and are in the process of being replicated nationwide. The Bhattarai government before it stepped down last month gave a target of 2017 to fit all four million households in Nepal with smoke-free stoves. That is also the year by which time all of Nepal’s 75 districts will hopefully be open-defecation free and all schools will have toilets. Even if these targets are not fully met, the impact on child survival and increasing lifespan of Nepalis will be huge.

Nepal has made the most dramatic progress in all-round human development among the world’s low income countries. As our coverage on page 16-17 shows, this has happened despite war, corruption, political disarray, and instability. Imagine how much more progress we’d have made if we had an actual peace dividend, elections, and better accountability and transparency.

But you won’t hear much about this in the media because the taking of lives makes news, not saving them.

Read also:

The Seventies