The anniversaries on Chomolungma this month may be a good place to start mending the reputation of Himalayan climbing

KOICHI CHMORI

When two groups of mountaineers come to blows on the highest mountain in the world, it is sure to make headlines around the world. The incident got added play because it was a slow news week in Nepal and elsewhere.

Unfortunately for us in Nepal, the news came just as the government was planning a series of celebrations in May to commemorate the anniversaries of the first ascent of Chomolungma by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay 60 years ago and the first traverse 50 years ago by Jim Whittaker and Nawang Gombu.

Both expeditions established the tradition that became the norm in Himalayan mountaineering: the successful partnership between (mainly) western mountaineers and the high-altitude Nepali porters that they hired.

Indeed, the admiration of mountaineers for the legendary endurance and understated determination of these inhabitants of the Khumbu put the Sherpa people and Nepal on the world map. The reputation and respect that the Sherpas have earned is a result of their hard work and sacrifice over the years, as well as their admirers who turned benefactors, like Edmund Hillary, Pat Devlin, and many others. The Sagarmatha National Park is a model for eco-tourism and the Khumbu region today has an average per capita income three times higher than the national average.

However, as Frances Klatzel argues there was always a simmering tension caused by the clash of cultures between the Sherpas and their employers. Sherpas of different expeditions work together for the benefit of all climbers in a season, while the mainly-western mountaineers have their own personal ambitions to reach the top.

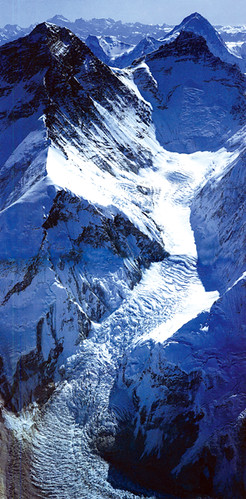

The Sherpas risk their lives every mountaineering season carving a route through the treacherous Khumbu Icefall, fixing ropes up the Lhotse Face, literally carrying some climbers along the summit ridge to the top, and rescuing those stranded on the Death Zone. And they have resented the cavalier attitude of some climbers who are so consumed by their ambition that they do not respect the mountain and others on it.

What adds a new dimension to this friction is the philosophical difference between commercial expeditions and Alpine-style climbers in the Himalaya. Partly because of the hefty royalties that they have to pay to climb eight thousanders in Nepal, expeditions sell slots to clients.

Alpine-style climbers, on the hand are purists, lean and mean climbers who go without oxygen, ropes, or Sherpas, usually on routes no one has done before. It was only a question of time before these styles clashed on a mountain like Everest which has a combination of both types of expeditions. Sure enough, this week there was a riot on the Western Cwm.

There are differing accounts of what happened between Camp II and III on the morning of 27 April. But both versions confirm that besides being a clash of cultures it was also a clash of egos. And it has to be said that the commercialism of Himalayan climbing has had a mercenary effect on what was once about exploration and adventure.

The Nepal government is partly responsible for this: by turning mountaineering into a cash machine and recycling very little of the revenue back to the people of the mountains. The prevailing national mood where might is right, greed is good, and a culture of settling scores through violence also rubbed off on the guides.

Good sense has prevailed, with both sides shaking hands and promising to make up. A lot of damage was done. No one won. Nepal lost. Collectively now, we have to try and restore the reputation of Himalayan climbing. The anniversaries in May is a good place to start.

Read also:

Escape to Pokhara

Mountain fight