Twenty-five-year-old Ram Devi Shakya arrived at the hospital complaining of high fever, conjunctivitis, muscle pain, and breathing problems for a week. Doctors diagnosed her with typhoid and began treatment. When her condition did not improve, they suspected meningitis, but ruled it out after negative test results. While the physicians awaited results of her blood sample to come back from Mumbai, she was given three new antibiotics but there was no progress in her condition. Ram Devi died on the tenth day of hospitalisation. The diagnostic report from Mumbai later revealed that she was suffering from leptospirosis.

Leptospirosis comes from the Greek word leptospira which means finely coiled organisms (spirochetes). In a study done at Patan Hospital and published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2004, leptospirosis ranked fourth (after typhoid, typhus, and pneumococcal pneumonia) as the cause of fever in over 800 consecutively admitted hospital patients. And yet for some reason leptospirosis is still overlooked by physicians and many medical colleges and residency programs don’t even include the disease in their curriculum.

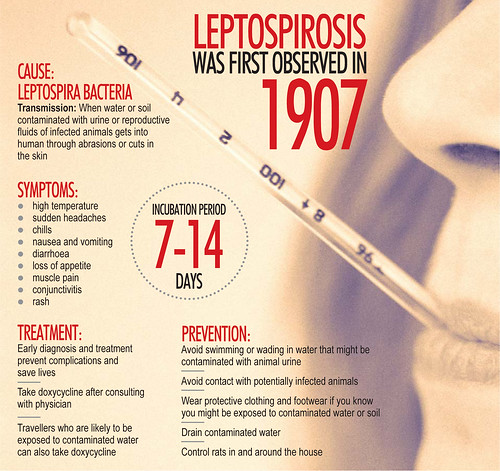

Leptospires are organisms which persist in the kidneys of a variety of animals including rats. Leptospirosis is acquired when water or soil contaminated with urine or reproductive fluids of infected animals gets into abrasions in our skin. The abrasions are typically followed by flu-like illness approximately one week later. In patients with mild Leptospirosis, the symptoms eventually subside. However, some like Ram Devi Shakya have severe leptospirosis, also known as Weil’s Disease which is characterised by respiratory and renal complications. These complications may lead to other organ failure and eventually death if the diagnosis is not made on time and medication not started immediately. Diagnosis is usually established by finding either high serum antibodies against leptospiraor polychromase chain reaction (PCR) test to look for leptospira DNA. Neither test is readily available in Nepal.

The highest incidence of this disease is in tropical countries like ours especially during the summer. In fact this disease is perceived to be common enough that many travel books advise visitors at high risk (for example those partaking in jungle safaris or recreational water sports like kayaking) to take prophylaxis. One such drug is doxycycline, but it should only be taken after consulting with a doctor who is well-versed in the prevalence, prevention, and treatment of leptospirosis.

If the doctors who looked after Ram Devi had used doxycycline from the beginning, she might have survived. Unfortunately, this humble and inexpensive drug is not used often in Nepal. Hence the importance of knowing what are the specific fever-causing bugs in our community with which Nepalis may be infected and empirically treating with appropriate antibiotics based on that knowledge even when laboratory back up is pending (specimen sent abroad in this case) or unavailable.