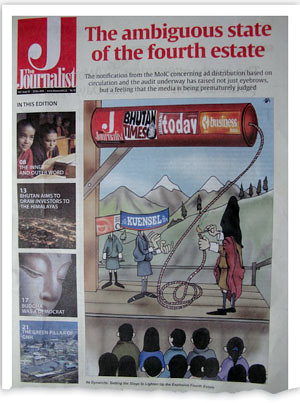

OLD NEW NEWSPAPER: The Journalist satirses the Bhutan government’s decision to restrict ads in a front-page cartoon.

Bhutan’s Prime Minister Lyonchhen Jigmi Thinley could not have been more blunt. He reminded newspaper publishers last week that their poor financial performance was not the government’s problem, but their own.

Since Bhutan embarked on a policy of media liberalisation in 2006, ending the era of only one newspaper, the number of newspapers has increased twelve fold. There are now eight weeklies, a daily, and four monthly newsmagazines in a country of less than 700,000 people about half of whom are illiterate. More than 80 per cent of the total $5million annual advertising in Bhutan is from the government.

“The responsibility of a government in a democracy is to create an enabling environment where the independence and freedom of media are respected,” Thinley said, “we have given you that.”

He added that the state had done more than it needed to by providing advertisements to publications without relevant circulation and private media should make a greater effort to stay in business.

None of the new publications have more than 2,000 readers and will not survive without government ads. Bhutan’s oldest newspaper, Kuensel, was the first modern media when it started in the early 1960s as a small government bulletin issued by the Department of Information.

Kuensel has undergone two radical transformations in the last 50 years. In 1986, it got a fresh Columbia graduate, Kinley Dorji, as its editor-in-chief who succeeded in changing it into a professional weekly newspaper in its present tabloid format. The second has been Kuensel’s transformation into an autonomous public sector enterprise in 1992 and the paper becoming the country’s only daily in April 2009.

Radio came to Bhutan as late as 1973, with an amateur station of the National Youth Association which was eventually upgraded and, in 1986, formalised as the national Bhutan Broadcasting Service (BBS which was also turned into a public sector corporation in 1992. It started tv broadcasts in 1999, four months before foreign satellite and cable tv were allowed and the advent of the Internet. In the past few years, six private FM stations have gone on air and with more than 100 productions so far, the local film industry seems to be thriving.

In 2006, two privately owned newspapers started publication: the Sunday newspaper Bhutan Times and the Bhutan Observer, a 14-page Friday weekly published from the border town of Phuentsholing.

For three years Bhutan Times managed to churn out a weekly of 32 pages, until it lost so much money the staff quit to start Sunday and The Journalist, in 2009. Bhutan Times is still continuing with the help of media company K4, which also supports Drukpa, a monthly news magazine launched in 2009.

Bhutan Observer is struggling for its share in what it calls ‘the already heated, hostile, and half-sized bajar that is the Bhutanese advertising market’. It has recently upgraded its online edition with dynamic, multimedia content.

In 2008, Bhutan Today was launched as a morning eight-page daily but has since gone bi-weekly. Business Bhutan, the country’s first financial newspaper, started as a weekly in 2009. All periodicals have a main edition in English and a thinner edition in Dzongkha, or have Dzongkha pages. Since 2010 three Dzongkha weeklies were started, Druk Nyetshul, Druk Yoedzer, and Druk Gyelyong. And in 2012, a bi-weekly broadsheet, The Bhutanese, also hit the stands.

Kuensel is still the most professional and effective newspaper and one of the few with a clear vision of its role in Bhutan’s social and political transformation. It is financed by subscriptions, advertising, and printing works for third parties, since government funding stopped more than a decade ago. With a total circulation of over 12,000 in English and Dzongkha, it reaches 130,000 readers. Its website has 15,000 registered members and attracts, on average, 1,500 visitors every day.

One of the most visible indications of Bhutan’s democratisation has been the opening up of the media, especially after the 2008 election. But with another election due on 23 April, Bhutan’s media is using its new freedom to cover the five contesting parties.

Lily Wangchuk of the new Druk Chirwang Tshogpa party is worried that the media space is constricting. She told The Bhutanese last month the media was vulnerable because it depended on ads on the government and few corporates. This year Bhutan dropped 12 points to 82 in the global Press Freedom Index.

Most new media seem more interested in revenue than building content or developing a reader base. Based on a circulation audit conducted last year, a Government Advertising Policy has been prepared with guidelines for a more targeted media approach. The Election Commission, however, has revoked its earlier decision to supply election ads only to government media.

For private media, this will bring temporary respite, but it looks like the road to a viable business model is long.

Ron Augustin is a print media management consultant based in Brussels who worked for printing projects in Bhutan in the 1990s.