There is greater awareness in Nepal about the links between killer infections and poor sanitation, and contaminated water

Two members of the British House of Lords were in Nepal to take part in the launch of the South Asia Regional Campaign on Sanitation this week in which MPs from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, India, and ex-CA members from Nepal took part. The campaign was organised by WaterAid and its partner NGOs and urged governments to ensure that the one billion people in the region have sustainable access to improved sanitation. Lord Ian McCall (right) of Dulwich, who is a surgeon, and Lord John Edward Hollister Montagu (left), Earl of Sandwich, spoke to Nepali Times this week.

CINDREY LIU

McColl: We’ve come to talk about the need for sanitation and related infrastructure. We’ve been struck with the fact that so often the talk is about how we need to get the economy right and then we can invest in infrastructure and sanitation. Actually, our experience in the UK has been the reverse. In the 1850s, when the River Thames became more and more like a sewer and it was called The Great Stink, the government was forced to take action. It was an enormous success. Improving sanitation improved health. We’re here to tell the government to invest in sanitation so that citizen’s lives can be improved bearing in mind that you have to get on with that rather than wait until the economy grows.

Montagu: I’ve been here before and I think Nepal is special. I believe in the power of civil society. When we visited Thecho village in Lalitpur, where the Nepali NGO Lumanti is working with the community members, I was impressed to see how the people themselves have been installing latrines, sometimes private sometimes for the community. Nepal has a long way to go, but it can do it because all these non-governmental organisations are working together with the government.

What can be done in Nepal to improve water and sanitation?

McColl: The important thing is to make sure the local infrastructure is right and that you’re treating people properly. Sanitation workers have more impact on public health than medical doctors. You have to have proper infrastructure and sewers have to be made properly. That is how you improve the whole public health system.

What can the government do?

Montagu: The government needs to work with NGOs and other organisations and support their work.

McColl: The government can make sanitation a high priority. That means, providing more funds, monitoring the results, and educating people so that benefits from sanitation can spill over into public health, tourism, livelihood and so on.

How do you see Nepal in 10 years in terms of access to sanitation?

Montagu: We want to see many, many more indoor toilets. This is very important in development and it’s happening already. It’s education as well, what you’re taught in school with hygiene. In some cases, bringing toilets inside the house can be perceived as a foreign initiative and likely to be rejected by the community.

McColl: The first thing is not for us to come in and tell people what to do, but to do everything with them and not for them so they have ownership. There are countries in Asia like Sri Lanka and Thailand which are quite advanced in sanitation and it’s not because they have more resources, but because they made sanitation a priority, which once done, they are able to do other things.

Where is the bathroom?

There used to be a time when you could tell you were nearing a village in Nepal when you saw signs of open defecation along the trails. Not anymore. Slightly more than half the population now use toilets. A government campaign backed by NGOs to declare VDCs open defecation free is yielding results and saving lives.

There is also greater awareness about the links between killer infections and poor sanitation and contaminated water. The number of children dying from diarrhoeal dehydration has come down by half in the last 15 years.

SOURCES: WATERAID, WHO, UNICEF

"Although statistics say access to water in Nepal is 62 per cent that figure

is debatable because it isn’t regular access. It means that people have some drops

of water sometimes during the week, and it’s not 24/7."

Ashutosh Tiwari, WaterAid

Nepal’s infant mortality declined by 42 per cent over the last 15 years, while under-five mortality has declined by 54 per cent. Still, one in every 22 Nepali children dies before reaching their first year and one in every 19 does not survive to the fifth birthday.

But there is still a long way to go. Poor drinking water, sanitation, and malnutrition are silent emergencies that don’t grab headlines like a bus crash or crime because the victims are mainly poor and they die silently, scattered across the land.

More can be done to improve the health of the children of poor Nepali families by building toilets than distributing medicines, more lives can be saved by installing a safe drinking water system in a village than starting a new clinic.

In parts of the country where most rain falls in three months, rainwater harvesting could help improve water supply and sanitation. Tyler McMahon of SmartPaani says rainwater collection could help communities, households, and schools on the high ridges.

“The conjunctive management of rainwater and groundwater recharge can help improve water security with minimal investment,” explains McMahon.

As slow as a snail

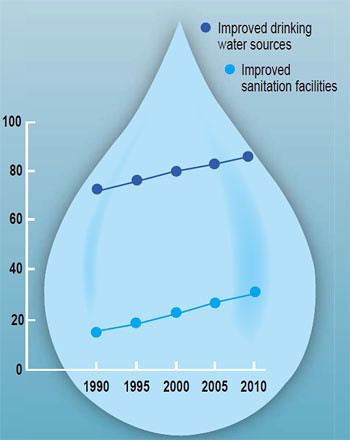

In 20 years Nepalis have nearly triplicate the use of sanitation facilities which is still very low just 30 per cent of the population. On the other hand, access to water has improved less than 10 per cent.

SOURCE: NEPAL HEALTH PROFILE 2010, WHO

Did you know

Access to water and sanitation is a human right

The average distance that women in Asia walk to collect water is 6 km

Nepal ranks 42 among 174 countries in total water resources (210 cu/km)

There are 209 NGOs working with water in Nepal.

Juanita Malagon

South Asia Regional Campaign on Sanitation