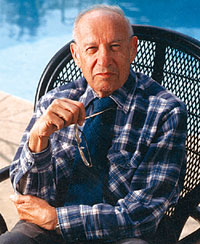

Peter Drucker, the man who invented the art of management, died in his sleep at home in California on 11 November. He was 95. Though most tenured professors at top-tier US business schools do not respect him enough to assign his writings to students, the ideas that Drucker put forth in his 38 books, many essays and lectures have long resonated with managers in for-profit and non-profit organisations worldwide. In my own spare-time reading of Drucker-with books bought from an extensive collection at Kantipath's Educational Book House-I have come away with three ideas that have influenced my thinking about business and management.

Peter Drucker, the man who invented the art of management, died in his sleep at home in California on 11 November. He was 95. Though most tenured professors at top-tier US business schools do not respect him enough to assign his writings to students, the ideas that Drucker put forth in his 38 books, many essays and lectures have long resonated with managers in for-profit and non-profit organisations worldwide. In my own spare-time reading of Drucker-with books bought from an extensive collection at Kantipath's Educational Book House-I have come away with three ideas that have influenced my thinking about business and management. Long before the widespread use of the internet, Drucker saw the rise of knowledge workers. He pointed out that a baker's son today need not grow up to be a baker as he would have done

40 years ago. That son might be a lawyer, an X-ray technician or an artist. This freedom to change one's profession from that of one's forefathers, argued Drucker, is a relatively new phenomenon in human history. And it has positive implications for the nature of work and management.

A member of a hospital management, for example, can express dissatisfaction over an X-ray technician's tardiness. But the management cannot do the technician's work, which is specialised. Given this, the challenge for anyone in management is to figure out how to get the best out of specialists or knowledge workers who work for their organisation. Viewed this way, being in management is akin to being a conductor who has to coax music out of orchestra members, each of whom is a specialist in playing an instrument.

Drucker's second insight was that managerial effectiveness can be learned through consistent practice. He had no use for CEOs as glamorous cover boys. Instead, he drew upon his consulting experiences to assert that managers' personalities, attitudes, values, strengths, weaknesses, extroversion or generosity made little difference if they were not effective and if they did not deliver the results for their organisations. He argued that a manager's job was to ask the right questions about what needs to be done, how to do it through action plans, assign people to do it and then get it done by keeping communications open. Anything else was simply a distraction.

Drucker wrote much on the art of self-management. He understood that different people learn the same thing differently. Some enjoy reading, some learn by writing, while others master new ideas by talking things over with many people. Drucker encouraged all to discover their own learning style and put that to work by honing their strengths. It is easier, he observed, to go from strength to strength than to try to turn a weakness into strength. He realised that knowledge workers do not necessarily do their best work within the traditional nine-to-five work schedule and suggested that management think out of the box to get more productivity out of employees, whose creativity would drive the innovations that businesses everywhere need today.

Drucker saw ambitious, highly educated and competent young people becoming partners of law or consulting firms at the age of 35 and then getting thoroughly bored with the work they do, while remaining too scared to leave work to find their true calling in life. He suggested that they spend several hours a week volunteering at non-profit entities-schools, museums, hospitals, theatre groups, music ensembles-so that they could share their expertise with organisations that desperately need management skills but coulnt afford them.

Indeed, all of Drucker's writings point to one conclusion: that the art of management, regardless of where it is applied, has the power to do much good for humankind. May his soul rest in peace.