It's late afternoon in the courtyard of the Changu Narayan temple. Dogs lie listlessly in the sun, and pigeons feed on grain as visitors wander around the premises taking in the stone sculptures and miniature carvings that date back to the Lichhavi era.

It's late afternoon in the courtyard of the Changu Narayan temple. Dogs lie listlessly in the sun, and pigeons feed on grain as visitors wander around the premises taking in the stone sculptures and miniature carvings that date back to the Lichhavi era.

A couple of curious Dutch tourists join a crowd of onlookers watching local workmen struggle to reinstate a statue on its pedestal in front of the main Narayan temple.

One night last month, the gold-plated statue of Bhupatendra Malla and two other images disappeared from the temple courtyard.

The statue of Bhupatendra Malla was found the next day by a cowherd, partially buried in a forest about a kilometre away, and was reinstated this week. The two other images have not been recovered.

Directed by the temple priests, the workmen weld and cement the statue to its moorings, after which they attach iron bars all around it, replacing the iron lattice window around the almost 300-year-old statue of Bhupatendra Malla and his queen.

"We're trying to make it as secure as we can. But there's no guarantee that people will not try again," says Chakra Dhara Nanda Rajopadhyaya, a temple priest.

The first theft in twenty years-in the late 70s and early 80s four statues disappeared from the temple complex-has reinforced the need for caution. Nanda and other temple insiders are becoming used to the suspicious glances of visitors who wonder why they hover around the statues at all times.

"Ten to fifteen people live inside the temple complex and they have two policemen patrolling the vicinity," says a bystander. His brother found the statue in the nearby forest the day after it was stolen. "Probably it was too heavy to carry far," he conjectures.

J?rgen Schik, a connoisseur of Nepal's traditional art, says almost 90 percent of rare idols, as well as those of exceptionally high quality have left the country since the 1960s, and those that remain are less important or simply cannot be uprooted.

J?rgen Schik, a connoisseur of Nepal's traditional art, says almost 90 percent of rare idols, as well as those of exceptionally high quality have left the country since the 1960s, and those that remain are less important or simply cannot be uprooted.

Schick first arrived in Kathmandu in 1973 as a tourist, and was struck by the wealth of culture concentrated in Kathmandu Valley.

His aim of putting together a comprehensive book detailing the Valley's heritage changed when on his travels he began to notice empty niches, holes in temple walls and mutilated statues-the work of professional, international art-theft groups.Photographs of numerous Hindu and Buddhist images taken by Schik during his travels in the Valley in the early 80s feature in the 1989 book by Lain Singh Bangdel, art historian and former vice-chancellor of the Royal Nepal Academy, Stolen Images of Nepal (Royal Nepal Academy).

Schick's own book, The Gods are Leaving the Country: Art Theft from Nepal, was published in German the same year and carried pictures and accounts of some of the stone and bronze sculptures that disappeared from Nepal in the 70s and 80s. An English version was published in 1997.

The work of both, one an academic whose research spans 30 years and the other an avid art watcher who spent seven years painstakingly documenting the Valley's icons, is detailed proof of the plunder of Nepal's 2,000-year-old cultural history. In the absence of reliable records at the Department of Archaeology, the two books are the only existing evidence that enables Nepal to claim that cultural artefacts works have disappeared from the country.  Like Bangdel's book, the aim of Schik's book-apart from providing evidence of the theft-is to change the purchasing policies of western collections and lay the ground for the return of stolen artefacts. "The 90s have experienced less art theft. I guess there's not much left to steal, and attitudes are changing too. The market is shrinking," says Schick.

Like Bangdel's book, the aim of Schik's book-apart from providing evidence of the theft-is to change the purchasing policies of western collections and lay the ground for the return of stolen artefacts. "The 90s have experienced less art theft. I guess there's not much left to steal, and attitudes are changing too. The market is shrinking," says Schick.

In August 1999, based on details in Stolen Images of Nepal, a private American collector returned four idols. The images-a ninth century Buddha image from Bhinchhe Bahal Patan, a 10th century Garudasana Vishnu image from Hyumat tole in Kathmandu, the mutilated head of a 12th century Saraswati image from Pharping and a 14th century Surya image from Panauti's Triveni Ghat-are now in the National Museum at Chhauni.

An image of Uma Maheswor which disappeared from Wotol in Dhulikhel in 1982 was returned last year by the Museum of Indian Art Berlin and now lies in the Patan Museum, where Dhulikhel residents feel it is more secure than it would be in a temple. (See "Return of the gods," #5) "Given the insecurity of our openly-kept statuary, I don't think it is a good idea to reinstate it in its original location, yet," says Bel Prasad Shrestha, mayor of Dhulikhel. He doesn't discount the possibility of the statue being stolen again.

Over the years, numerous idols have disappeared from in and around the area. Other than improve the lighting in temple complexes and alert the police and Chief District Officer of the need to patrol areas where there are statues of value, Shrestha doesn't see what else he can do. "Given the large gap in the economic condition and intellectual status of the Nepali people, it's difficult to do much."

Shrestha and his colleagues do, however, hope the statue will return to its rightful, if not original place one day-under a town restoration project Dhulikhel is planning to carry out, the mayor hopes to build a separate temple for the statue. "The gods would truly have returned, then," smiles the mayor.  In Changu Narayan, the priests lay part of the blame for the disappearance of statues on the guthis. Initially local watchmen took turns to guard the temple area and were paid for their service in kind, with grain. But the guthis stopped the practice and decided to pay them a sum in cash that can only be described as nominal. As a result, says Rajopadhyaya, the watchmen are simply not motivated to look out for their charges.

In Changu Narayan, the priests lay part of the blame for the disappearance of statues on the guthis. Initially local watchmen took turns to guard the temple area and were paid for their service in kind, with grain. But the guthis stopped the practice and decided to pay them a sum in cash that can only be described as nominal. As a result, says Rajopadhyaya, the watchmen are simply not motivated to look out for their charges.

The dozen or so policemen who patrolled the area after the earlier thefts has now dwindled to two, after they were dispatched to other parts of the country to tackle the Maoist insurgency.

"It isn't only the temple complex, but the surrounding neighbourhood too that we have to patrol," says one of the policemen on duty.

Where the stolen items will land up is anybody's guess. According to INTERPOL, only five to ten percent of all stolen cultural property is ever recovered. Some of these idols, worshipped by generations of Nepalis, lie in art galleries, museums and private collections in Europe or the US. A 1990 Sotheby's catalogue on Himalayan And Southeast Asian Art showed a 15th century sculpture of Laxmi Narayan. The sculpture was lifted from Patko tole of Patan in 1984. Another stone sculpture from Patan is in the Denver Museum in the US. And the Guimet Museum in Paris, one of the world's leading museums displaying South Asian Art has an 11th century idol of Uma Maheswor, stolen in 1984. Nepal's laws governing ancient art prohibits the departure of any item more than a hundred years old.

"It used to be just there," says a resident of Bhaktapur's Nasamana Tole, pointing to an empty, moss-covered niche. Just a couple of yards away from the spot is a fake statue of Laxmi Narayan, made to replace the original 800-year-old black granite Laxmi Narayan statue that was stolen in 1984. According to Bangdel's book, eight other sculptures are missing from the immediate vicinity. More than aesthetic works of art, the idols have a deeply religious significance. They were never just museum pieces, but part of the everyday lives of thousands of Nepalis.  Art watchers estimate that over 1,000 art works have been smuggled out of the country, many in the 70s and 80s. The remaining idols in Patan, Bhaktapur and Kathmandu have been placed behind ugly iron bars or cemented to the ground to deter thieves. But this hasn't prevented a spate of art thefts in recent months, including the loss of Buddha images from Swayambhu Maha Vihar, and statues from Patan Durbar Square and Chobar. And those are only the ones that have been reported as stolen.

Art watchers estimate that over 1,000 art works have been smuggled out of the country, many in the 70s and 80s. The remaining idols in Patan, Bhaktapur and Kathmandu have been placed behind ugly iron bars or cemented to the ground to deter thieves. But this hasn't prevented a spate of art thefts in recent months, including the loss of Buddha images from Swayambhu Maha Vihar, and statues from Patan Durbar Square and Chobar. And those are only the ones that have been reported as stolen.

Because the trade in stolen art invariably takes place across borders, with statues and objets d'art changing hands in many countries before reaching a final buyer, international regulations can provide some degree of protection to artefacts, even if they are not well-protected at home. One major international legislation is the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the means of prohibiting and preventing the illicit import, export, and transfer of ownership of cultural property. Nepal ratified the convention in 1976, and there are currently 91 signatories to it. It will help if countries with important art markets like Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom join as full-fledged state parties.

The 1995 UNDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects and other international legal instruments on illicit trade deals with the issues insufficiently covered by the UNESCO Convention. In late August, UNESCO organised a symposium on the illicit trade in cultural property, which recommended creating a website to be managed by the Department of Archaeology to raise international awareness about the missing cultural property of Nepal, and establishing of a tri-partite investigating commission, including representatives of the Department of Archaeology, the division of customs and the Nepal Police.

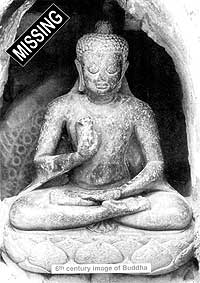

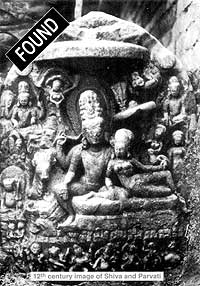

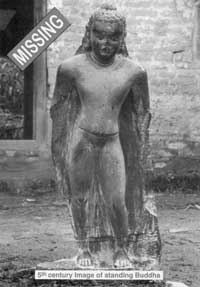

The symposium also adopted what it called the Kathmandu Declaration, urging the government to update laws against trafficking in heritage property. As part of its awareness raising campaign to protect cultural heritage, UNESCO has issued postcards of stolen cultural objects, some more than 1,500 years old. (See illustrations.)