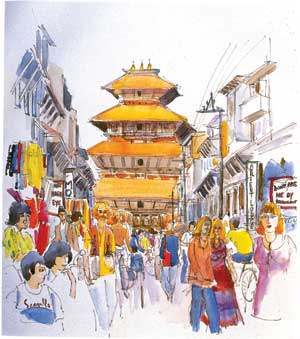

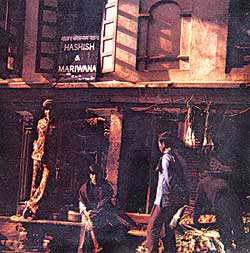

Way back when the war was in Vietnam and not Afghanistan, when protest was in the air, and when people wore flowers in their hair, you came to Freak Street. That's Jhonchen to us. The hippies, the Rastafaris, the flower children searching for happiness and nirvana, all arrived in the thousands, travelling overland in their Mercedes Benz buses, praising Krishna, Rama and other deities that surprised the local populace a little-the Bobs Dylan and Marley and the Beatles. They converted the pig alley to Pie Alley and Swoyambhu to Monkey Temple. The winds of change were sweeping through the world and by some curious chance they dumped everyone in Kathmandu, near Basantapur, from the infamous Charles Sobraj to your regular old Hare Krishna. And the locals looked on with amazement as they swooped down like locusts and consumed in days what might be the annual marijuana consumption of a small island population. Veni, vidi, vici. This small, happy population changed the fate of not just the Valley, but the entire nation. Nepal was to remain a tourist destination forever after.

Way back when the war was in Vietnam and not Afghanistan, when protest was in the air, and when people wore flowers in their hair, you came to Freak Street. That's Jhonchen to us. The hippies, the Rastafaris, the flower children searching for happiness and nirvana, all arrived in the thousands, travelling overland in their Mercedes Benz buses, praising Krishna, Rama and other deities that surprised the local populace a little-the Bobs Dylan and Marley and the Beatles. They converted the pig alley to Pie Alley and Swoyambhu to Monkey Temple. The winds of change were sweeping through the world and by some curious chance they dumped everyone in Kathmandu, near Basantapur, from the infamous Charles Sobraj to your regular old Hare Krishna. And the locals looked on with amazement as they swooped down like locusts and consumed in days what might be the annual marijuana consumption of a small island population. Veni, vidi, vici. This small, happy population changed the fate of not just the Valley, but the entire nation. Nepal was to remain a tourist destination forever after.

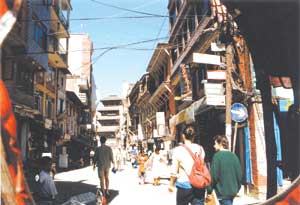

But that was a long time ago. You still come across the name every once in a while in guidebooks that try to write a summary of Nepal's modern history, but Freak Street is no more. It's been decades since the last hippie moved out of here. The few that remain are only figures lost somewhere in time, trying hard to recollect the days they spent in blissful oblivion in Kasthmandap, or New Age yuppies in disguise trying to recreate an era they missed. When Nepal finally declared marijuana illegal in 1972 it was a blow to the heart of Kathmandu's original tourist hub. It had played its part, but was already giving way to the adventure-seekers on the lookout for high mountain treks, white water rafting and the Chitwan jungle safaris on sale. Hippies were replaced by trekkies, and their world was in Thamel.

"Change is inevitable, we have to go along with the times. The hippie era is a thing of the past. Now we have to look towards the future," says Mohan K Mulepati, owner and managing director of the Himalaya's Guest House and Coffee Bar in Jhonchen. Mulepati ran the Himalayan Cold Drink Store in Jhonchen back in 1965. "The money I earned from the shop I put into the guest house," he says, recalling the glory days.

"Change is inevitable, we have to go along with the times. The hippie era is a thing of the past. Now we have to look towards the future," says Mohan K Mulepati, owner and managing director of the Himalaya's Guest House and Coffee Bar in Jhonchen. Mulepati ran the Himalayan Cold Drink Store in Jhonchen back in 1965. "The money I earned from the shop I put into the guest house," he says, recalling the glory days.

Indeed. Today when if you were to venture forth to Jhonchen (a Newari word meaning \'lane of Newars'), you get the sense that finally, reality has sunk in and people are finding ways to move on, while proudly clinging to the worldwide fame their little street still has. Even if you catch a faint whiff of pot from an old pipe someone chanced upon, be warned, drugs are a thing of the past here. "It is either a loner or the increasingly problematic-and misguided-Nepali pushers who think they can get a market here. We are trying hard to deal with this," says Uden Shrestha, a young Kathmanduite who recently got together with three friends to open a new hotel called Monumental Paradise, right on Jhonchen. The hotel stands out compared to its admittedly faded neighbours, in large part because while those are old buildings with most of their traditional features either long \'renovated' or simply badly maintained, this modern hotel decided that it would go with the increasingly popular traditional red-brick fa?ade.

This is one of the first steps in what looks suspiciously like the gentrification of Freak Street. The phenomenon of gentrification takes place in every city, but the pace at which this has been happening in the last decade or so has been remarkable. Places like New York, where the Internet boom fuelled a real estate boom, saw an almost incredible progression of turning factory floors into cyber-hubs. There's been no such boom in Nepal, but the economy is growing, and increasing urban over-crowding and sprawl mean there are fewer alternative tourist venues in the heart of the city.  Baudha may be \'the next Thamel', but it is still a Thamel-like tourist ghetto. A revitalised Freak Street would be a different order of experience altogether. But the place needs help for that. Right now, residents and entrepreneurs there are trying hard to share the gains from a fairly small number of visitors, so most do not believe they have the time, energy or resources to try and turn \'Freak Street' into Jhonchen.

Baudha may be \'the next Thamel', but it is still a Thamel-like tourist ghetto. A revitalised Freak Street would be a different order of experience altogether. But the place needs help for that. Right now, residents and entrepreneurs there are trying hard to share the gains from a fairly small number of visitors, so most do not believe they have the time, energy or resources to try and turn \'Freak Street' into Jhonchen.

"Thamel has money, and the advantage of being able to expand, but we cannot go beyond the limit," says Udab Shrestha, the owner of Restaurant Oasis established in 1985. Making matters worse is the Rs 200 entry fee, sometimes described as a service charge, that the Kathmandu Municipality now charges tourists visiting the World Heritage Site Basantapur-Hanuman Dhoka area. Residents of the neighbourhood are furious. They claim that this more than anything in recent years has affected their business. "I had to cut my staff from 32 to 12 because of revenue losses after they started collecting entry fees," complains Shrestha. Businesses say that since so many visitors to Basantapur are backpackers on tight budgets, when faced with the entry fee they spend less in restaurants and souvenir shops.

But Rashmila Prajapati, programme manager of the Hanuman Dhoka Darbar Square Conservation Program started by the Kathmandu Municipal Corporation (KMC) reasons, "UNESCO World Heritage sites all around the world have service fees, we are not the only ones. It takes a whole lot of money to preserve these sites and the bottom line is that neither the KMC nor the Department of Archaeology has this kind of money. We are only trying to help."  Whatever the justification, local entrepreneurs seem to neither appreciate nor want this help. For the first time in Nepal something akin to a class-action suit is in the courts. The municipality's regulation is being challenged in a lawsuit filed by 507 people. What will happen in the courts is anybody's guess, but there is another side to the story-there is no sign that tourists are decreasing in Basantapur. When we visited Prajapati's office, the 74th day the fee was being charged, over Rs 5 million had been collected from close to 26,000 tourists.

Whatever the justification, local entrepreneurs seem to neither appreciate nor want this help. For the first time in Nepal something akin to a class-action suit is in the courts. The municipality's regulation is being challenged in a lawsuit filed by 507 people. What will happen in the courts is anybody's guess, but there is another side to the story-there is no sign that tourists are decreasing in Basantapur. When we visited Prajapati's office, the 74th day the fee was being charged, over Rs 5 million had been collected from close to 26,000 tourists.

The programme has many projects in the pipeline to improve Basanatapur. In addition to maintenance of the Heritage structures, these include building public toilets, installing street lights, putting on cultural shows in the square, and beefing up security. This last is aimed at keeping away hangers-on and souvenir vendors. Perhaps, since they are, after all, an important part of the informal economy, the hawkers themselves could be made part of the landscape, installed under semi-permanent canopies they could rent for a small fee. If all his pans out like the municipality hopes it will, it will be a good thing for Basantapur.

But will it be as positive for Freak Street? Mohan Mulepati offers an alternative. "Instead of charging people to just walk on the street, they could have taken fees to, say, enter the Kumari Ghar. Or they could have cultural programmes in Kasthamandap and make those who want to view them pay a decent amount. The municipality says it will do things for the neighbourhood with the money they raise, but whether they will and what they do remains to be seen."  Jhonchen's monetary concerns are understandable, but maybe we should begin by asking what kind of future is possible for it. The fame and fortune that hashish brought cannot be replaced and it is best to not even try. Thamel, where the money is as in-your-face as the tourists who throng it, is actually not doing so well-undercutting and oversupply mean business would be going steadily down, even if the tourists weren't. That is little consolation for Jhonchen, which lacks both capital and confidence.

Jhonchen's monetary concerns are understandable, but maybe we should begin by asking what kind of future is possible for it. The fame and fortune that hashish brought cannot be replaced and it is best to not even try. Thamel, where the money is as in-your-face as the tourists who throng it, is actually not doing so well-undercutting and oversupply mean business would be going steadily down, even if the tourists weren't. That is little consolation for Jhonchen, which lacks both capital and confidence.

The average tourist-and Kathmanduite-about-town-would like an alternative to Thamel, with its excessive hassles, its claustrophobic sometimes racist environment and the sea of other tourists all doing much the same, or watching each other do it. As a pair of Dutch tourists put it, "Every tourist wants to make a special journey, but Thamel is just like any other tourist ghetto."

There will always be people who want another Thamel, another Pat Pong or King's Cross. Jhonchen could step in for those who want a somewhat quieter, more contemplative place to be that still has all the amenities they need. Instead of fifteen variations on the same bar, Jhonchen's space constraints could be used creatively to have smaller, fewer, but altogether more individual places to hang out. You could step from a cosy pub to an imaginatively-lit square at midnight, just to see how beautiful it looks. As for rooms, there would be fewer, but they could range from the relatively upscale to the fairly basic, and they could all be better designed. With the limited supply there would be no undercutting, so business would be healthier. Souvenir vendors could be organised, and prices could be standardised. It is a small enough area, so Jhonchen and its environs could conceivably be kept clean all year round.

What all of this needs is proper planning. If the municipality and the local business and residential communities could get together and agree on their vision for Jhonchen, this little area could be a haven for tourists and Nepalis alike, a place to just go and relax, watch the beauty and let your guard down.

The entrepreneurs seem to be gearing up to bring the glory back. The young residents of the area have new ideas and hope for a better future, and they have slowly started shaking things up a little. Arun Manandhar, owner of a uniquely \'Freak Street' eatery called Caf? Culture thinks there is hope. He, for one, is willing to change. And he thinks he knows just how to get other people involved as well-community action. "Locals were not involved as a community, and we lost out." Uden of Monumental Paradise echoes his sentiments: "We need to fuse the old and the new-we cannot just stick with the "Freak" idea." The veteran Mulepati, who has seen so much, advises residents not to give up. "We have to be patient in this business. We have been really trying to get people to accept this," he says.

And it is remarkable, how the entire Jhonchen community seems to have a new, enthusiastic sense of ownership and desire to get their act together and do well for themselves. Like-minded residents and businesses have even formed a committee called the Darbar Square Promotion Committee, which came out with a free tourist brochure that includes a small map of Kathmandu, a bigger one of the Darbar Square and Jhonchen, and information regarding the various deities in the area. The committee is also trying to guard the region from drug pushers while adding streetlights and keeping dustbins on the road. "But this is not enough, we have much more to do and far to go," says a hopeful Uden. Modern-and well-designed-buildings like the Basantapur Plaza with its very upmarket stores should be a sign for our times. Jhonchen doesn't need to be totally posh, but it could be a little edgier, a little more modern.

Freak Street is no more, long live Jhonchen.