In a cold and rainy day this week in Thamel, and Gandharbas are not to be seen, nor their sarangi heard. But if you enter the alley beside the Jump Club and walk up to the two-room office of the Gandharba Art and Culture Organisation, you'll always find someone here-laughing, teaching, chatting and, naturally, singing.

In a cold and rainy day this week in Thamel, and Gandharbas are not to be seen, nor their sarangi heard. But if you enter the alley beside the Jump Club and walk up to the two-room office of the Gandharba Art and Culture Organisation, you'll always find someone here-laughing, teaching, chatting and, naturally, singing.

To any visitor they will offer a kind smile and a cup of tea from the Gorkha Restaurant below. This, they say, is where their strength lies, in unity, the same kind they say with a little smile, they have helped bring about in Nepal with their songs. There is a great dissertation for some ethnomusicologist or anthropologist out there in exploring the significance of Gandharba songs in nation building.

A long, long time ago, it is told, before the gods populated the earth with humans, there were musicians that entertained the divinities. The Gandharbas fiddled away on their arbaaz, the original version of the sarangi, and the apsaras danced to their tunes.

This idyllic state of affairs continued until the powers that be decided that humans had outlived their usefulness in the higher realms, and so would be divided into castes and sent down to earth. The banishing of the unsuspecting humans from the heavens was obviously an occasion for great celebration and all were invited to a grand feast. Each caste was seated in its assigned place and served food and wine by comely apsaras. Everyone arrived on time, except the Gandharbas. They came after all the food had been apportioned to all the castes. They could not be turned away, hungry, and so it was decided that all the other humans would give a small share of their meal to the Gandharbas.

And that is how it has been for centuries.

Gandharbas, the minstrels of Nepal, have been singing for their supper as long as anyone can remember. Music is not just their profession, it is their culture, their life, their reason for being. Unfortunately, while they have earned much fame from it, the money has been significantly slower to come. And in these rapidly changing times, the challenge facing the Gandharbas is not just how to keep their culture alive, but how to keep their community itself going.

Gandharbas, the minstrels of Nepal, have been singing for their supper as long as anyone can remember. Music is not just their profession, it is their culture, their life, their reason for being. Unfortunately, while they have earned much fame from it, the money has been significantly slower to come. And in these rapidly changing times, the challenge facing the Gandharbas is not just how to keep their culture alive, but how to keep their community itself going.

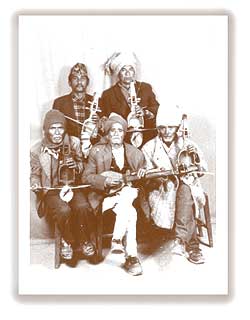

No one knows where the Gandharbas were originally from, but most come from the western development region districts of Tanahun, Chitwan, Lamjung, and Gorkha. For centuries they have been Nepal's mass media, travelling through the thousands of villages singing oral histories of gods, kings, and commoners. Their more memorable songs tell of King Prithvi Narayan Shah's feats that led to the unification of Nepal, of the fire that ravaged Singha Darbar 30 years ago, and of Jung Bahadur hunting tigers in the tarai. But the allure of Gandharba music for most Nepalis lies in the songs they sing of loves lost and won, of the pain and suffering of the common person, such as Amai le sodhlin ni khoi chhora bhanlin ("Mother may ask where her son is."See box for translation.) of a man who goes to battle and is wounded. Knowing that he is about to die, he sends a poignant letter to his family.

Unfortunately, the changing musical tastes of Nepalis are posing quite a challenge to the Gandharba's music. The minstrels who wandered have already given up travelling through the villages, and most of them prefer to come to cities such as Kathmandu and Pokhara. More than just the disappearance of an art form, the decline of the Gandharba's traditional livelihood also signals the loss of a vital source of Nepal's folk history.

Sadly, even those Nepalis who understand the significance of the musical tradition of the Gandharba community do not seem to associate the art form with the people, an irony not lost on the musicians. "Nepalis love the sarangi but not the Gandharba," laments Sanu Kancha Gandharba president of the Gandharba Art and Culture Organisation. At a recent meeting, the intellectuals of the capital talked about the role of the sarangi but not the man behind the instrument, he tells us.

At another human rights meeting, virtually every other dalit community was mentioned but not a word about the Gandharba. And that was why Sanu Kancha didn't attend the second meeting. "I was heart broken. Why should we go there again? We will survive on our own," he says. The name Gandharba is found in numerous Hindu holy texts such as the Purana and the Swasthani, but mention in holy books is no guarantor of a good life-although Gandharbas are often offered food, clothes and money, their caste bars them from entering the houses of other Nepalis. And though singing is how they would like to continue making their living, they are forced to take on odd jobs simply to survive. Few have land they can call their own, and many are heavily in debt.  Sanu Kancha himself has had a difficult, not untypical life. Nearly two decades ago, at the age of 13, he started "running" the streets, first of Basantapur and then Thamel. "During the early days I just sang and walked the streets, hoping for a kind ear to listen to us and maybe praise us and give us a few rupees. But one day I found that there were some real admirers, especially tourists who wanted to buy the sarangi. And that was how everything started for us." The Gandharba Art and Culture Organisation was established in 1995 on the advice of a kind-hearted American. It is the only organisation of its kind in Nepal and has 110 members and a branch in Pokhara. The organisation is entirely self-sustaining-members make the four-stringed sarangi and sell them to tourists, and donate a quarter of the proceeds to the organisation.

Sanu Kancha himself has had a difficult, not untypical life. Nearly two decades ago, at the age of 13, he started "running" the streets, first of Basantapur and then Thamel. "During the early days I just sang and walked the streets, hoping for a kind ear to listen to us and maybe praise us and give us a few rupees. But one day I found that there were some real admirers, especially tourists who wanted to buy the sarangi. And that was how everything started for us." The Gandharba Art and Culture Organisation was established in 1995 on the advice of a kind-hearted American. It is the only organisation of its kind in Nepal and has 110 members and a branch in Pokhara. The organisation is entirely self-sustaining-members make the four-stringed sarangi and sell them to tourists, and donate a quarter of the proceeds to the organisation.

"It isn't a very dependable or constant source of income, given the current trends in tourism, but even at times when there are plenty of tourists on the streets, it is difficult to earn more than Rs 2,000 -Rs 3,000 per week," says Sanu Kancha. Other than singing and selling sarangi, madal (Nepali double sided drum), and basuri (flute), some Gandharbas have started teaching folk dance classes to curious tourists, or music to the odd Nepali music lover. Bikas Yogi, a musician, pays Rs 2,000 a month for a daily hour-long course in playing sarangi. Yogi is enthusiastic about the four-stringed Nepali violin. "I have always loved the music of the Gandharbas, but never had time to learn it. I finally took time out and it has been worth it."

People like Yogi fulfil an important role. As the GACO works to preserve the community's heritage, its members find it heartening when others, especially other Nepalis, take an active interest in it. Right now the organisation is working to save as many old lyrics and songs and record them for posterity. GACO has got together the oldest and most talented of the community to cut an album called Gandharba ko mutu (The Heart of the Gandharba), which will have 15 original Gandharba songs. It is expensive, says Sanu Kancha, but the community is doing its best to make sure that it works out.

Many younger members of the community say that preservation of culture alone is not enough. Education is their long-term goal, and 23-year-old Raj Kumar Gandharba says he acutely feels the lack of a basic education. "People call us gaine, it hurts. We cannot answer back because we are simple people. If we were educated, things might have been different," he says. The community is increasingly concerned about ensuring its future generations do not labour under this handicap. Sanu Kancha, for instance, is sending his two sons to an English school, even if it means having to get by on only one meal a day.

GACO, for its part, is sponsoring two children in Tanahun district and is planning to institute more such scholarships in the future. Says Sanu Kancha: "I hope education will help them become better human beings, and we hope they never forget that they are Gandharbas even if they become doctors or engineers."

Mother may ask where her son is

House to house, door to door

They came to recruit

Asking whether we would like to have a job

Our hearts concurred

The major saab in the corner, he checked

The squint-eyed and the deaf, they went out

The healthy went to the hospital and were taken in

Six months from that day

We paraded barefoot

Many are wounded in the chest, and many more in the head

When I remember the wound in the head, my heart shakes

Mother may ask where her son is

Tell her I'll come later

Father might ask where his son is

Tell him I am still fighting in the battlefields

Elder brother might ask where his brother is

Tell him his share of property has increased

Younger brother might ask where his brother is

Tell him the family has decreased

Elder sister might ask where her brother is

Tell her to return the gift she brought from her house

Younger sister might ask where her brother is

Tell her there is no gift for her this time

Sister-in-law might ask where her brother-in-law is

Tell her to cut a goat and have a feast

My son might ask where his father is

Tell him to remove his cap

My daughter might ask where her father is

Tell her to save her honour

Brothers will talk of me at the family meetings

Father will talk of me for six months, a year

Mother will talk of me forever

My beloved wife might ask where I am

Tell her to break her bangles and her necklace

Wipe her sindoor, and that her path is now open

Childhood was spent in play

My youth in the service of the government

I wanted to come, the enemy stopped me

I didn't come, death met me