Until a year ago, Jeet Bahadur Pun was like many young Nepalis, living and working far from home. The 25-year-old put in long hours at a gas station in Saudi Arabia to send money back to his family in Dhanja in the insurgency-hit district of Baglung. Jeet had been feeling out of sorts for some time, always fatigued and nauseated. When he started having to take bathroom breaks constantly and realised he was rapidly losing weight, Jeet finally went to a doctor and was told that his kidneys were failing fast.

Until a year ago, Jeet Bahadur Pun was like many young Nepalis, living and working far from home. The 25-year-old put in long hours at a gas station in Saudi Arabia to send money back to his family in Dhanja in the insurgency-hit district of Baglung. Jeet had been feeling out of sorts for some time, always fatigued and nauseated. When he started having to take bathroom breaks constantly and realised he was rapidly losing weight, Jeet finally went to a doctor and was told that his kidneys were failing fast. By the time he got home, Jeet's illness had progressed to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), a result of chronic renal insufficiency. In lay language, his kidneys had been deteriorating for some years and had by then pretty much stopped functioning and were unable to excrete toxins, which was why Jeet was experiencing such a multitude of symptoms.

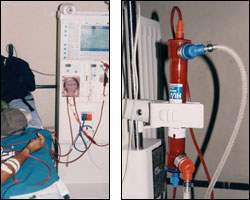

Jeet soon realised that this is one of the worst diseases a poor person can have in Nepal. To live even a semblance of a normal life, he either had to find a donor and have a kidney transplant, or have his blood drained, purified and pumped back in two three-hour sessions every week. A transplant would be cheaper in the long run, if Jeet could first find a donor and then spend at least Rs 1 million for the entire procedure, after which he'd have to take expensive drugs all his life.

But transplants aren't really an option in Nepal: the law is vague, and even if one of the few trained professionals who can perform the procedure wants to take the risk, a strong mafia is said to control the kidney trade, which the law forces underground.

The alternative, haemodialysis, is expensive and traumatic, especially for underprivileged people and those without a strong social support network. Jeet makes the eight-hour journey from Baglung to the capital twice a week. Since there is no one to take care of him here and he must arrange everything, from food and accommodation to medication, by himself, his costs are higher than the normal Rs 20,000 or so per month. The only other dialysis facility in the country is even farther away for Jeet, at the BP Koirala Memorial Cancer Hospital in Dharan.

Dhana Lama is in some ways luckier. Dhana, now 30, also suffers from ESRD and has been on haemodialysis for the last three years. Kathmandu-based Dhana pays for his treatment with the help of donations from people who read about him in the papers occasionally. Dhana, who says he has always been very independent, is from a lower-middle class family and lives in a three-room house with his father, a brother with a drug problem and an ageing aunt. He managed to finish his ISc from the Nepal Science Campus and was working towards a BSc from Tri-chandra College, funding his education by doing odd jobs-sometimes he was a computer technician, at other times a dye master like his father-when his kidneys started to fail three years ago.

Today, Dhana has still not found a donor and the dialysis machine is his only link to life. He knows this will not last forever. "All the other people who were undergoing dialysis when I started have already died, I'm quite a survivor," he says, smiling bravely. Motivated by his struggles, Dhana has become actively involved in helping others like himself, as well as trying to raise awareness about renal disease and what can be done about it. This year he along with other patients he met at Bir Hospital started a non-profit called the Nepal Kidney Patients Association, which is trying to set up a network of ESRD patients.

Today, Dhana has still not found a donor and the dialysis machine is his only link to life. He knows this will not last forever. "All the other people who were undergoing dialysis when I started have already died, I'm quite a survivor," he says, smiling bravely. Motivated by his struggles, Dhana has become actively involved in helping others like himself, as well as trying to raise awareness about renal disease and what can be done about it. This year he along with other patients he met at Bir Hospital started a non-profit called the Nepal Kidney Patients Association, which is trying to set up a network of ESRD patients. Dhana's never-say-die attitude is perhaps one of the reasons he has received so much media attention. Unfortunately, the media usually fails to see what this dying man is really fighting for. A three-hour dialysis session at one of the three functioning machines at Bir Hospital costs Rs 250. Patients need the procedure twice a week-three times, if you follow international therapeutic norms-and each time a new set of apparatus is required, including artificial kidneys, pipes and syringes to pull and transport blood, saline water, as well as buckets. Add to this the costs of the expensive imported medication the patient needs, and the monthly medical expenses of a person with renal failure are as much as Rs 20,000.

Dhana says that what makes life for someone like him truly hard isn't just the burden of having to treat an expensive disease, but also the sometimes unprofessional attitude of the nurses and even the doctors. When Dhana complained about how rude the nurses sometimes were at the Bir Hospital in an interview with a local newspaper, the medical staff there refused to treat him when he returned. "We know that we are getting treatment at a very cheap rate but the nurses and doctors sometimes act as though our lives mean nothing, as if they are doing us a favour," says Dhana, recalling how a renowned surgeon came up to him after the interview and called him a threat to the survival of the hospital.

Dr Sudha Khakurel, head of nephrology at Bir Hospital admits that mistakes can sometimes happen but also tells us about the good her department is doing. "You have to understand that al though we are running at a severe loss, we have not stopped anyone's treatment. Most patients just cannot even afford it. They drop out by themselves after a few months." The hospital recently acquired two more computer-operated dialysis machines. The nephrology department of the hospital and patients like Dhana lobbied the Ministry of Finance for months in order to be able to take possession of the machines-the hospital administration could not pay the customs duty due on them and the machines were stuck at customs for two months. Bir Hospital currently treats 22 patients with chronic renal insufficiency a week, and approximately 35 with acute kidney failure, which is reversible a year.

Almost every private hospital provides dialysis, but at a cost that is usually ten times higher than that charged by Bir Hospital. This is why Dr Rishi Kafle, a nephrologist, set up the National Kidney Centre, a not-for-profit hospital that treats kidney problems. There has been no official survey of the scale of renal problems in Nepal, but specialists such as Dr Kafle estimate that nearly 2,200 patients seek treatment every year for chronic renal failure. The numbers might seem low, but the danger of ESRD is that patients often do not even know their kidneys are failing them until both the kidneys stop functioning.

The Centre started treating patients five years ago when a German woman Beate Vogt decided to donate dialysis machines to Bir Hospital. When she realised how much red tape that would involve, she gave the machines to Nepal Kidney Centre instead. Vogt has donated 16 machines already and comes to Nepal once a year with supplies and medication for kidney patients. The Centre, which is funded entirely by Vogt, charges between Rs 2,500 and Rs 3,000 per session. Unlike a dialysis session at Bir Hospital, patients do not need not to organise any of the other essentials such as the artificial kidneys or tubes. The Centre has set aside two machines for patients with HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis B and C. "The main drawback of this disease is the expense. The wealthy may be able to afford dialysis all their lives, but it's a curse to even middle-class families. In countries outside SAARC the cost per session is at least $200. We charge $40, but how can you expect most Nepalis to afford this?" asks Dr Kafle.

The Centre started treating patients five years ago when a German woman Beate Vogt decided to donate dialysis machines to Bir Hospital. When she realised how much red tape that would involve, she gave the machines to Nepal Kidney Centre instead. Vogt has donated 16 machines already and comes to Nepal once a year with supplies and medication for kidney patients. The Centre, which is funded entirely by Vogt, charges between Rs 2,500 and Rs 3,000 per session. Unlike a dialysis session at Bir Hospital, patients do not need not to organise any of the other essentials such as the artificial kidneys or tubes. The Centre has set aside two machines for patients with HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis B and C. "The main drawback of this disease is the expense. The wealthy may be able to afford dialysis all their lives, but it's a curse to even middle-class families. In countries outside SAARC the cost per session is at least $200. We charge $40, but how can you expect most Nepalis to afford this?" asks Dr Kafle. For people like Dhana and Jeet, doctors say the only the only feasible way to live with the condition is to have a kidney transplant. It's not a perfect solution, but it can go a long way in making life easier for them. The problems with organ transplants, and kidney transplants in particular, are legion. First there is the law. The Nepal Human Body Organ Transplant Act 2055 was created without consulting any medical professionals with adequate knowledge of transplant surgery. Article 15 (4) of the Act asks doctors to certify that the donor of any organ will not immediately die or become disabled due to the donation, and article 15 (5) asks doctors to certify that the organ donated will grow back naturally. Liver transplants, thus, are allowed, because the donor's body regenerates those parts of the liver than are taken out. Kidneys do not "grow back", and even though a person can function with only one kidney, donating it becomes illegal, doctors have no way of proving that there is no causal relation between the removal of a kidney and death, even a few years down the line.

Second, there simply aren't enough trained transplant surgeons in Nepal. For kidneys, there are only two, Dr Asarfi Shah and Dr Ashok Rana. Dr Shah performed three successful kidney transplants in 1996 "within the limited perimeters of the law" at the Everest Nursing Home. Dr Shah says that the problem isn't just that the law is vague, but that it is unlikely to be changed. "The people who can change the regulations to allow legal, safe kidney transplants do not do so because the mafia that controls the illegal trade in kidneys is too powerful," says Dr Shah. He mentions that foreign investors interested in transplant operations backed out a year ago when they faced the legal challenges. At the very least, say doctors who work with kidney failure, the government could ensure that the medication is produced domestically, which would significantly reduce the financial burden on patients.

Dr Shah says he is so frustrated, he plans to make his voice heard by contesting the next elections as an independent candidate, just as he did in the last elections in 1999. "There needs to be a professional voice in parliament. It is precisely when they formulate laws on things like medical matters that professional advice is necessary," explains Dr Shah. He says he doesn't have political ambitions, but merely wants to be able to practice medicine with full freedom.

Unless things change, in the law books and on the ground, people like Dhana and Jeet will continue to be forced to hustle, despite their illness, and find ways to raise the millions they don't have that are needed for dialysis and prohibitively expensive medication. Alternatively, they will be have to get involved in a murky struggle to find an illegal donor, or go to India for expensive surgery.