This is not Nepal's war-torn midwest, it is 50km from the capital. It is a tale of two villages which are coping differently with violence and conflict. But neither is far from fear, and the people there don't want anything to do with a conflict being fought ostensibly for their liberation.

This is not Nepal's war-torn midwest, it is 50km from the capital. It is a tale of two villages which are coping differently with violence and conflict. But neither is far from fear, and the people there don't want anything to do with a conflict being fought ostensibly for their liberation.

"It was like a dream," recalls Nirmala Tamang, a hotel owner in Dapcha. Her business thrived as this little village, 20km east of Dhulikhel on the new Sindhuli highway, reaped the benefit of the construction boom of the past three years.

When the ceasefire broke down on 27 August, the Maoists stepped up their activities here and the military began counter-insurgency operations. Nirmala's business went into a tailspin. "Now all we hear is silence, we are ruined," says 45-year-old Nirmala. Her husband, Narendra, agrees: "This place has turned into hell."

Dapcha was ideally placed to become a major business hub, as it was at the crossroads of the new highway to remote villages up the Mahabharat hills. There was work for everyone as the highway construction began: porters, truckers, wholesalers, traders and the service industry that sprang up around these occupations. After seven months of peace, the Maoists broke the ceasefire and Dapcha's good luck ran out.

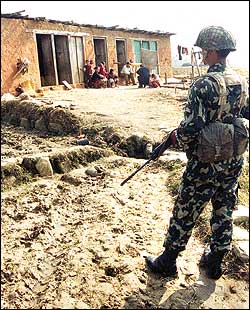

Extortion by the Maoists took their toll, and things became impossible because of constant inspections and searches by the security forces. The closely-knit village has now thinned down to a few households. More than half of the 50 families have abandoned their homes and live in Banepa. The once bustling bazar is now closed and shuttered.

You can smell the fear and terror in Dapcha as people whisper about the brutal deaths of two young boys. On 17 November, 11-year-old Min Bahadur Lama was on his way home when he spotted a pressure cooker with a Maoist flag sitting in the middle of the busy road. He went to take a closer look, despite warnings from his friends. As soon as he removed the flag, the bomb exploded, killing him on the spot. Earlier, another Dapcha youngster, 18-year-old Sanat Shrestha was killed on 3 September by Maoists who thought he was an army informer.

The level of psychological trauma on families is so high that the community's social fabric has fallen apart. Nobody pays social calls, everyone stays at home behind closed doors. Children aren't allowed out, and by dusk Dapcha's few shops are locked. By six in the evening, all you hear are doors being banged shut. An hour later, there is complete silence and not even the dogs are barking.

People beg strangers to leave them alone. "Please go away, leave us alone," they whispered to us through heavy wooden doors when we ask for bas. The family that dared to take us in said we were to leave before dawn the next morning. The news of outsiders in the village travels fast and either the Maoists or the army would soon come calling to ask questions. Who were they, what did they want?  "Restless days with sleepless nights is our never-ending routine," says Nirmala's 16-year-old daughter Sarita. "All I want to do is finish school and get out of here." When we knocked on their door, the family looked suspiciously at us through a chink in the door. It was time for the Maoists to come for their monthly donation. "It is the end of the month, that's when they come to collect," Sarita explains softly, not daring to even call the rebels by name. She admits that the strong army presence in the area and constant checking by the security forces makes her feel more secure.

"Restless days with sleepless nights is our never-ending routine," says Nirmala's 16-year-old daughter Sarita. "All I want to do is finish school and get out of here." When we knocked on their door, the family looked suspiciously at us through a chink in the door. It was time for the Maoists to come for their monthly donation. "It is the end of the month, that's when they come to collect," Sarita explains softly, not daring to even call the rebels by name. She admits that the strong army presence in the area and constant checking by the security forces makes her feel more secure.

While the people in Dapcha have drawn inward and closed themselves off, down the road in Daraune Pokhari villagers have done just the opposite. A year ago, they built a 7km motorable road to reach their village through personal contributions from each of the 45 households. With just Rs 700,000 and within five months, they carved a round across the steep mountainside. "This road proves that we can build our own village and we are really proud of ourselves," says Min Tamang who started a club with his friends to organise similar development activities. Locals actively support the club's self-improvement plans. "Raising funds is not a problem if we are organising activities that benefit us," he says.

But even here, the fear of the spreading violence is never far. Villagers have heard of the situation in surrounding villages, and even though no one has been killed here, things are getting tense in Daruane Pokhari. Maoist extortion is on the rise, and the locals are afraid of retaliation from the Maoists for the recent deaths of two senior Maoist commanders at the hands of the security forces.

"One of them was in charge of 500 militia members," says a woman at Daraune Pokhari worried about reprisals against villagers for being informers. But others are more confident: "Our lives are normal here and we have nothing to fear because we are sincere and hardworking," says Sunil Tamang.

Indeed, schools here are still running, none of the teachers have left. Terrace farms are being tilled and harvested, roadside stalls never run out of tea or customers and shops still trade. Says Min Tamang: "All we do is mind our own business. We are neither close to the army nor the Maoists."

All names in this piece have been changed to protect the identity of the villagers at their request.

Baburam offers a deal

Maoist ideologue Baburam Bhattarai this week proposed elections for a constituent assembly supervised by a UN-type security force. The proposal is mentioned almost as an aside in Bhattarai's column in the Maoist mouthpiece, Janadesh, and proposes that the Maoist army and the government security forces could be demobilised during the election.

Political pundits see it as a significant change in the Maoist stance on the constituent assembly demand and the first time ever that they have proposed demobilisation. The government has not reacted to the proposal, but is not likely to agree to it. It had flatly rejected the Maoist constituent assembly demand earlier this year, leading to a collapse of the seven-month ceasefire in August.