"Miam hamnida. Very, very sorry." Choi Sung Kak, a well-known South Korean writer, stood in front of Chandra Kumari Gurung in Kimche village near Pokhara last month, head bowed and palms together. Choi wasn't fumbling for words to express guilt for any action of his own, he was apologising for his country.

"Miam hamnida. Very, very sorry." Choi Sung Kak, a well-known South Korean writer, stood in front of Chandra Kumari Gurung in Kimche village near Pokhara last month, head bowed and palms together. Choi wasn't fumbling for words to express guilt for any action of his own, he was apologising for his country. Chandra Kumari went to Korea to work as a labourer in 1992, a healthy and excited woman nearing 40. In 1993, she disappeared.

A meal Chandra Kumari couldn't pay for was the start of the nightmarish six years and four months that this normal, balanced Nepali woman spent in Korea's national psychiatric hospital.

After her release, Chandra Kumari, with the help of angry South Koreans, sued the Republic of Korea and Dong-san Jang, director of the Chung-ryang-ri mental hospital. "Because of the carelessness of the Korean police and state, she ended up in the hospital, where she had no business being," said Choi, who is also vice-president of Nature Trail, the Korean NGO that helped Chandra return home on 14 June, 2000.

After her release, Chandra Kumari, with the help of angry South Koreans, sued the Republic of Korea and Dong-san Jang, director of the Chung-ryang-ri mental hospital. "Because of the carelessness of the Korean police and state, she ended up in the hospital, where she had no business being," said Choi, who is also vice-president of Nature Trail, the Korean NGO that helped Chandra return home on 14 June, 2000. Of the nearly 2,000 Nepalis working in Korea, 99 percent are illegal. Many have been there since they went to South Korea legally since 1991, under a "trainee program". Since that program expired, there has been no formal labour agreement between the two governments. Activists like Choi and Nepalis considering working in South Korea hope that Chandra's case will set a precedent for better labour laws for migrant workers.

When Korean police arrested Chandra Kumari she couldn't explain to them that she had lost her wallet. She had no valid papers, and couldn't communicate to the police her contact address and phone number. "She just insisted she was Nepali, not Korean, and said "I don't know" in Korean to every question they asked," said Lee Seong-gyou, a journalist working on a documentary about Nepali migrant workers. With her Gurung looks she could have mistaken for a Korean. "But there's no excuse for such a devastating mistake," Lee told us.

Throughout her stay in the psychiatric hospital, Chandra Kumari was kept alone in a room. A doctor there familiar with Nepal met her, and contacted Lee Geun Hoo, a member of Nature Trail and founder of the Yeti Caf? in Seoul. Lee, a professor who has been coming to Nepal regularly for 15 years, visited the hospital. The story was publicised by Nature Trail, and created an uproar in Korea.

Soon after her release from the hospital in April 2000 Korean lawyer Suk-tae Lee helped Chandra file a lawsuit demanding compensation for her incarceration, and a formal apology from the South Korean state. The court arrived at a ruling 5 November, and awarded Chandra just over $23,500. Choi says the amount is insulting, and that NGOs and Chandra's lawyer are preparing to appeal. "Still, no amount of money can ever right the wrong that the Korean state committed against Chandra," Choi told us when in Nepal last month to hand over money that the Korean public has donated to Chandra.

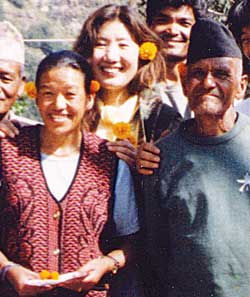

"She's a totally different woman today from the one we met in Korea," says Choi. Chandra Kumari is now taking care of her elderly father. (See also "Seven years with my Korean fathers")