It is when you can swing your 8*24 binoculars at a rustle in the bush, focus quickly and whisper, "White-rumped Shama" that you know you have arrived into the fascinating world of Himalayan bird watching.  For a small country, Nepal racks up an impressive 850 species of birds-more than the entire North American continent. New bird species are found every year. We owe our amazing diversity mostly to very fortuitous geography and great altitude variation. From the Kosi Tappu at barely 90m above sea level, the terrain rises to nearly 9,000m-all within 160km as the lammergeyer flies. The country lies smack dab on an east-west Himalayan divide of which the Kali Gandaki Valley forms a distinct avian boundary. It is bound between the "Paleo-arctic" realm to the north (Tibet, Siberia) and the "Indo-malayan" realm to the south (India, south-east Asia).

For a small country, Nepal racks up an impressive 850 species of birds-more than the entire North American continent. New bird species are found every year. We owe our amazing diversity mostly to very fortuitous geography and great altitude variation. From the Kosi Tappu at barely 90m above sea level, the terrain rises to nearly 9,000m-all within 160km as the lammergeyer flies. The country lies smack dab on an east-west Himalayan divide of which the Kali Gandaki Valley forms a distinct avian boundary. It is bound between the "Paleo-arctic" realm to the north (Tibet, Siberia) and the "Indo-malayan" realm to the south (India, south-east Asia).

Of the species found in Nepal, about 620 breed and live in Nepal. Another 124 breed in the  neighbourhood but live here in significant numbers. Then there are another hundred or so migratory species that transit through Nepal in their long-range migrations from Siberia to Africa, Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

neighbourhood but live here in significant numbers. Then there are another hundred or so migratory species that transit through Nepal in their long-range migrations from Siberia to Africa, Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

Nepal is a major destination for bird watchers from Europe and Japan. They come in droves from December through March, before the monsoons set in, when the days are warm and nights not too chilly. The truly dedicated oviparous obsessed can be seen rustling in the bush on the slopes of Shivapuri, and others have flocked this week to Kosi Tappu the richest site for migratory birds. You can tell them apart from regular tourists by the  powerful binoculars slung around their necks, sturdy shoes and no late carousing so they can be up at the crack of dawn to watch the early bird catch its worm.

powerful binoculars slung around their necks, sturdy shoes and no late carousing so they can be up at the crack of dawn to watch the early bird catch its worm.

Kosi Tappu Wildlife Reserve sits at the point where the mighty river disgorges itself out of the mountains before entering India. Kosi Tappu is located on the migratory route of birds travelling down from Tibet along the Arun River-all factors that contribute to the great variety of birdlife found here. At 88m above sea level, the Kosi Barrage and the big reservoir that it has built up is the favourite haunt for ducks and geese. Robert  Fleming, Sr (one of the authors of the classic Birds of Nepal) counted 32,000 ducks of 19 species here before the preserve was established. Today, with protection, there must be more.

Fleming, Sr (one of the authors of the classic Birds of Nepal) counted 32,000 ducks of 19 species here before the preserve was established. Today, with protection, there must be more.

Less numerous, but equally magnificent, are the bossy looking black-necked adjutant storks, and the flippity finch larks. But habitat destruction is a worry. Bharat Basnet, the Managing Director of The Explore Nepal Group which runs the Kosi Tappu Wildlife Camp, has managed to spark interest in local schools for bird watching. Some sharp eyed, smart school students eventually join  as local guides. "What is more important than a specific species is the habitat. If the habitat is preserved then all the inhabitants will be protected," Bharat told us.

as local guides. "What is more important than a specific species is the habitat. If the habitat is preserved then all the inhabitants will be protected," Bharat told us.

Don't despair if you can't make it to the tarai. Kathmandu has some fabulous bird-watching areas in the foothills surrounding the Valley. If Nepal is a treasure house of birdlife, then Phulchoki south of Kathmandu is Nepal's bird and butterfly vault. Deforestation along the margins of this once-protected broadleafed forest and raucous picnickers have spoilt the atmosphere somewhat, but Phulchoki is still alive with birds. The peak soars to 3,000m from the valley floor and has sunbirds, finches, minivets, barbets and the elusive and legendary spiny babbler-the only other bird species that is endemic to Nepal (the other being a sub species of the kalij pheasant). Many birdwatchers make regular pilgrimages to Phulchoki to look for the spiny babbler, but you have to be very lucky to see it.

A morning hike in Godavari leads us to a small clearing in the woods. Right in front are half a dozen kalij pheasants feeding on the ground. Our arrival disturbs them, and the kalij erupt into wings and flap off into the undergrowth. Within Phulchoki's vertical variation of 1,500m and 70 sq km area live 265 species of birds-one-fourth of all bird species found in Nepal. Some 86 of the bird species on Phulchoki are migratory. Godavari resident, Mahendra Singh Limbu, is a lepidopterist-turned-bird watcher. He tells us, "At least six of the species found in Phulchoki are rare and endangered." The blue-napped pita, rufus throated hill partridge, blue-winged laughing thrush, grey-sided laughing thrush, grey-chinned minivet, Nepal cutia and the spinny babbler, are all threatened. Limbu says that the success of community forestry around Godavari and Lele means that many of the birds like the kalij and Alexandrine parakeet are returning.

The Pipar region near Ghasa in the Annapurna region at 1,400-3,300m was made famous to bird watchers by long-time Pokhara resident, Col Jimmy Roberts. An enthusiastic bird watcher and collector, Roberts donated his entire collection of pheasants, fowls, pigeons and several other smaller species to the Fulbari Resort's aviary in Pokhara before he died four years ago. The Pipar region has all six species of Himalayan pheasants found in Nepal as well as their lowland cousins, the blue peafowl and the red jungle fowl. The cheer and the swamp frankolin have not yet been included in the endangered list even though they are threatened. Hunting has now been banned in Pipar and the local community is helping to conserve the Himalayan snowcocks, chakor partridges, and the cheer and the koklas pheasants.

The Annapurna area is home to half of Nepal's bird species. Another bird paradise is the Makalu Barun National Park and Conservation Area in the northeast. This rarely visited park reserves a total of 440 different species of birds, of which fourteen are rare eastern breeders.

Loss of forests, wetlands and grasslands are a threat to Nepal's bird diversity. Areas like Phulchoki, Ghodaghodi Lake in the western tarai and Mai Valley in the east have not yet been declared protected areas. There is a move to declare Phulchoki and Chandragiri ranges nature sanctuaries, but that may take time. In the past 15 years, forests in Nepal's midhills have returned, and with them many of the resident and migratory birds.

What worries conservationists is that tarai forests are disappearing fast, and this is where most bird species are. When the hardwood forests go, marshes are drained, pesticides are used indiscriminately, then birds disappear. "Conservation of Nepal's forests is vital, for the future of people as well as for birds," write Carol and Tim Inskipp in their book, A Guide to the Birds of Nepal. "The aim should be to balance the needs of local people, trekkers and the natural environment." Most of Nepal's endangered birds are dependent on forests, and 90 percent of these species are also found in Nepal's national parks and nature reserves. The answer lies in bolstering conservation in these areas, and what better way to do that than to use income from bird watching tourism to protect Nepal's rich bird diversity.

Where to birdwatch

Where to birdwatch

Kathmandu Valley

. Discerning birdwatchers make a day trip to Phulchoki and Godavari Botanical Gardens to the south-east of the Valley, a subtropical broadleaved forest. Those lucky may catch a glimpse of the elusive spinny babbler. Avoid on public holidays-people and birds are inversely proportionate.

. Gokarna Safari Park is just east of Kathmandu and easily accessible. The park opens early and charges a small fee. Give yourself half a day to admire the owls, wintering thrushes and flycatchers who favour the mature trees in the park.

. Above Balaju is Nagarjuna, a 2015m mountain that has a protected forest, providing a rich habitat for birds. Expect to see kalij pheasant, Nepal fulvetta and red-billed blue magpie. If you have the whole day, don't miss a hike to the secondary forest on the far side of the mountain.

. Missed the spinny babbler at Phulchoki? Shivapuri Wildlife Reserve could be your second chance. What it lacks in accessibility, it more than makes up by the number of species found within its forest. Make a weekend of it. Take a tent and a fellow bird enthusiast.

Royal Chitwan National Park

Fly or bus down to this lowland valley of sal and riverain forests. The 480 bird species recorded here is complemented by many modes. To see them-canoe, hike or take an elephant safari.

Kosi Barrage and Kosi Tappu Wildlife Reserve

Nepal's largest wetland attracts plenty of migratory species and just as many bird enthusiasts who vote this as their top birdwatching destination. Base for the annual Migratory Birds Festival in February.

Royal Bardia National Park

With terrain similar to Chitwan, this park is rich in western lowland species. A two-day bus ride from the capital will get you within binocular distance of changeable hawk-eagles and Bengal floricans.

Sagarmatha National Park

The mountain scenery is unbeatable and forms a stunning backdrop to high altitude species like the Tibetan snowcock and altai and alpine accentors. Jorsalle, the park entrance, is a day's walk from Lukla.

Annapurna Sanctuary and Modi Khola

Trek from Pokhara to the source of the Modi to the south-west located sanctuary. The dense rhododendron, oak and bamboo forests have half of Nepal's bird species, including a few endemic to the country.

High fliers

High fliers

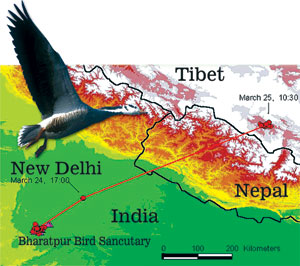

Tracking bar-headed geese by satellite during their twice-a-year trans-Himalayan migration shows the endurance, stamina, determination and navigation skills of these high-flying birds. Satellites tracked a wired goose while it flew from the Bharatpur Wildlife Reserve in north India, across western Nepal up to the Tibetan plateau, crossing three countries. The bird flew over 500km from near New Delhi, overflew Dhangadi, Jumla, across the "hump" to lakes north of Mustang in Tibet-a non-stop night flight lasting 16 hours and 30 minutes.

Birds in Nepal have also set amazing altitude records. Acclimatised Himalayan choughs, for instance, have been seen by mountaineers soaring at nearly 8,000m above the South Col below the summit of Sagarmatha. George Shaller in his book, Stones of Silence, reports seeing bar-headed geese at an incredible 9,000m above the Himalaya. Even if that was a fluke, and the flock was coasting on an updraft in the jet-stream, there are plenty of regular sightings by mountaineers of geese honking their way past Dhaulagiri at 7,300m.

Some of these geese (karyankurung) are known to take off in spring from the banks of the Rapti River in the Royal Chitwan National Park, head due north and reach their cruising altitude by the time they arrive above Tatopani. Just sit by the Kali Gandaki in October or April and you see the traffic of geese and ducks quacking and honking as if this is an avian superhighway linking Siberia to Chitwan.

The theory explaining stratospheric bird flight is that the birds have been migrating along this route when the mountains were much younger and lower. They flew higher and higher as the Himalayan mountains were pushed up, and evolved better lungs and flying ability over millions of years. And you just have to watch Tibet-bound terns and ducks refueling at Gokyo Lake in early April to be struck by awe and wonder at these incredible birds.