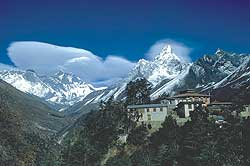

Sagarmatha National Park is a conservation success story, and a model for eco-tourism. The stately lichen-covered spruce and hemlock around Tengboche Monastery that had all but disappeared 25 years ago, are sprouting back. Juniper bushes near Pheriche show regeneration even though plant growth is extremely slow at these altitudes.

Sagarmatha National Park is a conservation success story, and a model for eco-tourism. The stately lichen-covered spruce and hemlock around Tengboche Monastery that had all but disappeared 25 years ago, are sprouting back. Juniper bushes near Pheriche show regeneration even though plant growth is extremely slow at these altitudes.

Journalists covering the 50th anniversary of the first Everest climb last spring, who were prepared to do the mandatory "trash on the Everest trek" stories, were pleasantly surprised to find the trails relatively litter-free.

But the Sagarmatha's success has come at a price. The growing affluence of the Sherpa villages, and the growth of tourism has boosted demand for timber. But the ban on logging inside the park has meant that the forests outside the park boundary have fallen under the axe. The rest of Khumbu's forests have become the victims of the park's success.

The rhododendron logs piled high at the office of the Armed Police Force at Lukla airport are pink and smooth to touch. They look as if they were felled recently. "The police cut our trees in our forests and we get blamed," whispers a local lodge owner.

Local villagers say the security forces are in cahoots with "powerful and influential people" to smuggle timber up to Namche Bazar. Park officials are aware that the deployment of additional security forces to guard the airport has increased consumption of firewood. But trees are being cut for construction timber.

The result is that while thick forests of pine drape the steep slopes of the Imja Khola and Bhote Kosi valleys inside the Park, the rhododendron and oak forests near Lukla have all but gone. The locals, who are not allowed to cut trees, are incensed that the police are openly chopping them down and carting them away. One conservation officer told us: "Villagers have approached us saying that they should also be allowed to cut down the trees if outsiders enjoy that privilege."

The Armed Police Force headquarters in Kathmandu chose not to make any comment.

The Lukla unit of the APF is supposed to get a generous supply of kerosene because it is deployed in a buffer zone where timber logging is prohibited. Ironically, the national park is guarded by the Royal Nepali Army, while the Armed Police Force is in Lukla only because it has to guard the airport.

The Sagarmatha National Park office at Namche raised this matter with the Armed Police commander last year, but the APF flatly denied it was poaching timber. The last warden who warned the police to stop the logging was forced by the armed police to stand all night in the freezing cold at the helipad in Lukla as punishment.

The Sagarmatha National Park office at Namche raised this matter with the Armed Police commander last year, but the APF flatly denied it was poaching timber. The last warden who warned the police to stop the logging was forced by the armed police to stand all night in the freezing cold at the helipad in Lukla as punishment.

Since then, relations between the park and the police have become further strained. The new park warden Gopal Bhattarai issued a notice against cutting trees in the buffer zone. An international conservation agency said it had asked the Royal Nepali Army to help bring the APF in line and get the police to stop cutting trees. "They stopped for a while, but it has started again," one official told us.

Many of the logs are transported into the park to build new lodges and monasteries. The logging mafia is well-oiled: in Chaurikharka, timber from Pharak and Phakding are mixed in with timber from lower Khumbu and Phaplu and taken into the park.

A few people have been caught and penalised, but a Rs 300 fine doesn't deter the criminals. "The fines don't cut into their profits, so of course these people return to cut more trees," said Kami Dorji Sherpa, chairman of the forest user group in Chaurikharka.

The number of trekkers and mountaineers in the park has climbed sharply from 4,000 in 1982 to its peak of 26,000 in 2000. Although the levels have dropped slightly since then, a mountaineer still uses eight times more firewood than an average trekker and 20 times more than a local Khumbu resident.

But not all the forestry user group members are honest. Some of its executive members have been known to misuse their authority to sell trees. They say they are selling the timber to repair trails and bridges, but more often than not, the money ends up building private tea houses and lodges that are springing up on the Khumbu trail-many of them funded entirely by the illegal timber trade.

Those in charge of protecting Sagarmatha's environment are now finding themselves in the unappreciated minority. "We try to protest, but the perpetrators have connections to powerful people," says a frustrated Sherpa tourism entrepreneur. "They don't cooperate, and instead try to make us the villains."

The locals still remember how their elected representative in the dissolved parliament, Bal Bahadur KC, freed timber smugglers from police custody two years ago. "Those smugglers were caught red-handed but they had the MP's blessings, and they are still involved in illegal logging. Everyone knows who they are," a local conservationist told us.  The Sherpas of the Khumbu have cultural and religious attachment to the protection of the natural environment. Nature here is regarded as the outer manifestation of the human soul. Rimpoche Nawang Lama of Tengboche monastery, a passionate environmentalist, is credited with restoring the forests on the spur where his shrine is situated. The abbot has also been active in the successful anti-litter campaign.

The Sherpas of the Khumbu have cultural and religious attachment to the protection of the natural environment. Nature here is regarded as the outer manifestation of the human soul. Rimpoche Nawang Lama of Tengboche monastery, a passionate environmentalist, is credited with restoring the forests on the spur where his shrine is situated. The abbot has also been active in the successful anti-litter campaign.

"Buddhists believe that the deities and spirits dwell in the trees, and the trees influence the weather, the harvests and the wellbeing of human communities," says the Rimpoche.

But some unscrupulous locals reportedly misuse the Lama's name to bypass laws on logging. A local politician flew out a large consignment of logs in a helicopter earlier this year, without a permit, despite a ban from the warden's office. He reportedly told park officials the timber was cut on instructions from the monastery. "These events have happened in the past," admits Namche lodge owner, Jangbu Sherpa. "Many people misuse the Lama's name but I doubt he knows about it."

After the Maoist rebels attacked their barrack at Salleri in lower Khumbu two years ago, the Royal Nepali Army has confined itself to its heavily fortified base on a hill overlooking Namche. Before the state of emergency, there were five posts at different points in the park. There are now only three. For chief warden Gopal Bhattarai, things are difficult enough without the depleted army presence.

The army takes up almost 80 percent of the national park office's budget, and that would have been money well spent if the military was actually enforcing conservation laws. "At the moment they aren't doing much. They are worried about their own security," says Bhattarai.

Another issue that complicates matters is that the responsibility for conservation of the buffer zone has not been handed to the park's jurisdiction. Dawa Sherpa, chairman of the buffer zone council, told us the official process is slowly moving towards a hand-over. But it is so slow that by the time it is transferred, the trees may all be gone.

The Department of Forestry has washed its hands off the buffer zone, while the park hasn't taken over. This bureaucratic limbo combined with apathy and greed has lead to wholesale logging. Looking up from the Lukla to Phakding trail, the slopes are littered with the carcasses of white logs stripped of their barks. The sound of axe on timber can be heard right across the valley, and occasionally a warning shout as another tree falls in the thinning forest.

Tougher buffer

Alarmed by the denudation in Lukla, Pharak and Phakding (above), the government declared the area the Sagarmatha National Park Buffer Zone in 2002 and with help from the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) will be continuing its 8-year-old community agro-forestry program here. Up to half of the revenue generated by the park from trekker fees will now be ploughed into conservation activities in the buffer zone. So far, the project has set up five community forest user groups, established nurseries and replanted entire mountainsides with seedlings. The project is also looking at alternative energy sources like solar and micro-hydro along the Lukla trail to reduce dependence on firewood.

Alarmed by the denudation in Lukla, Pharak and Phakding (above), the government declared the area the Sagarmatha National Park Buffer Zone in 2002 and with help from the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) will be continuing its 8-year-old community agro-forestry program here. Up to half of the revenue generated by the park from trekker fees will now be ploughed into conservation activities in the buffer zone. So far, the project has set up five community forest user groups, established nurseries and replanted entire mountainsides with seedlings. The project is also looking at alternative energy sources like solar and micro-hydro along the Lukla trail to reduce dependence on firewood.