from 1949 to 1953 is one of the few wars in which a conventional force defeated a revolutionary movement. Six Gurkha battalions were deployed in the war. But while military hardware, muscle and equipment were important, the political factor was paramount. Respect for civilian life and welfare, proper treatment and rehabilitation of prisoners were foremost priorities. There are other lessons as well for Nepal from this chapter of Brigadier ED Smith's book, Counter-insurgency Operations: Malaya and Borneo.

When the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), led by Secretary General Chin Peng, decided to fight his former ally, the British, after the Japanese surrender he was in a position to take over the whole country. He very nearly succeeded.

When the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), led by Secretary General Chin Peng, decided to fight his former ally, the British, after the Japanese surrender he was in a position to take over the whole country. He very nearly succeeded.

The guerrillas never numbered more than about 7,000, nevertheless they were at least as formidable as the Viet Cong were in the 1960s. If the campaign had continued to be mismanaged, as it was in the early stages, there is little doubt that the British would have had a Vietnam on their hands.

Having surprised the government, the MCP retained the initiative and successfully permeated the Chinese rural population through a "call" system with a small number of executives responsible for each sizeable village in such a way it was able to coerce the population into donating money, smuggling food and reporting on Security Force activities.

Of great significance, too, the terrain was to their advantage: the primary jungle gave plenty of cover in which to hide. Without the benefit of hindsight, there is no doubt that the future for democracy in Malaya looked bleak indeed to those who lived in the country during the first two or three years of the Emergency. This gave Chin Peng

a flying start.

Within two years of defeating the Japanese in the jungles of Burma, the British Army had concentrated its military training and thinking on nuclear and conventional tactics for a European theatre against a first-class enemy. As a result, the army had forgotten most of its jungle warfare techniques and expertise, learnt the hard way and at such high cost during the war.

Not surprisingly, the military tactics adopted by the MCP guerrillas were something quite new to the British officers. It was outside their pattern of warfare, involving as it did surprise attacks against soft targets and withdrawal into the jungle.

The police too were caught unawares and their Special Branch was far too small for the tremendous task that faced its members once hostilities began. In the battle for information during the first two years, the Communists undoubtedly had the advantage. Experience soon showed the need for military and police units to devote a great deal of attention to gathering information themselves. This was a painstaking process-it required a thorough knowlege of local activities and eventually relying on informers, handled by the Special Branch and backed up by observation.

One lesson learnt and occasionally ignored, thereafter, was the futility of mounting search and destroy operations in an endeavour to overcome a lack of intelligence. Senior commanders were to learn that those sort of operations were indeed a last resort, and likely to succeed only if the guerrillas abounded in such numbers that the war was already a lost cause.

Once the infantry had learnt to move in the jungle and do it better and quicker than the guerrillas, then they were able to wrest the initiative from them, augmented by better training and self-discipline. Great importance was given to developing accurate, timely intelligence at all levels. Individual policeman and soldiers had to understand the importance of gathering every scrap of information for detailed analysis: all this required imagination, patience and skill. Moreover, correct handling of surrendered terrorists was necessary so that they could be won over to the government side and persuade their comrades to abandon the movement.

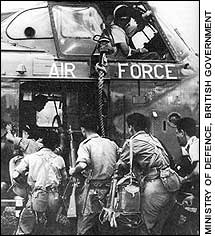

When the guerillas moved into the more isolated stretches of jungles, imaginative use of air power by the British became all-important-to gain mobility by employing helicopters, for logistic resupply of patrols, and for air strikes. But it is worth noting that without aerial reconnaissance and direction-finding by the light aircraft, it would have proved virutally impossible to locate and successfully attack the guerrillas.

Much more important than the military aspects of the Emergency were the political, social and economic measures set into motion first by Sir Henry Gurney, and after his death in a guerrilla ambush in 1951, by Gen Sir Gerlad Templer. The decision to re-settle over 600,000 Chinese squatters ended up isolating the militants from the portion of the Chinese population which had in the past helped them.

The setting up of New Villages, the formation of Home Guards, and the far-reaching decision to arm them demonstrated to all and sundry that they were being trusted. The imaginative decision to allow districts which cooperated with the government to become "White Areas", showed those sitting on the fence that there was a chance of a better life if the government was successful in the end.

The government also showed itself capable of being tough, but it was deemed to be essential that every action taken by the government was within the law. At no time was there martial law, at no time was a rile of government terror imposed.

Another lesson was the need to coordinate all government activities: political, military, social and economic. And the most effective way of doing this was through coordinating the activities of national, state and district committees all under the leadership of one "supremo" at the centre of affairs.

Perhaps the most important of the lessons learnt in Malaya-but only after several false starts-was that the firepower of government forces needs handling with skill and with care, a lesson that has often been ignored in subsequent campaigns. Guerrilla forces are seldom destroyed by large concentrations of fire: gunships and body counts do not win counter-insurgency campaigns because in the long term they will terrorise and alienate many more members of the civilian population.

Some 11,000 people died during the Malaya Emergency, including 2,500 civilians. But if unrestrained firepower had been used that total would have bee increased ten-fold and the campaign lost.

Perhaps the biggest advantage that the Malayan government had when dealing with the threat posed by the Communists was the fact that there was no open border as there would be in Vietnam and Thailand. While it is right to state that Malaya remains a classic example of how a counter-revolutionary campaign should be waged, it must be remembered that Chin Peng had no safe sanctuary, no open border, and by the very nature of Malaya's multi-racial society, his appeal to help met with little response from the Malays and Indians, especially after the initial wave of terror failed to win the day.

Counter Insurgency Operations:

Malaya and Borneo

ED Smith

Ian Allan, 1985 London