The Supreme Court this week said the government is not doing enough to check air pollution in Kathmandu Valley, and ordered a ban on all vehicles 20 years old in two years.

The Supreme Court this week said the government is not doing enough to check air pollution in Kathmandu Valley, and ordered a ban on all vehicles 20 years old in two years.

Pressure from green groups and the Supreme Court may be the last hope for Kathmandu's citizens. But unlike New Delhi, where the Supreme Court forced the government to make cleaner CNG fuel mandatory (see page 5), our courts have in the past been uninterested or unable to enforce their own orders. In fact, the Iraq war and the ensuing fuel shortage may show us how clean Kathmandu's air used to be.

Even so, this week's decision paves the way for action to address worsening pollution. Besides more dust and soot particles, there are new poisonous emissions. Carbon monoxide levels on Kathmandu sidewalks are five times higher than they were 10 years ago. The area of Kathmandu Valley where suspended particulate concentrations of 75 micrograms per cubic metre has doubled in the past five years.

Benzene is the latest poison. This carcinogenic gas is a by-product of the kerosene used to adulterate petrol and diesel. Fuel aduleration is so blatant and widespread that one survey last year showed half the diesel sold in gas stations in Kathmandu was mixed with subsidised kerosene, while the percentage of kerosene in petrol was 40 percent. Last year, the government formed a task force to look into adulteration, but hasn't licked the problem.

Measurements by the Ministry of Population and Environment (MoPE) show benzene concentrations of nearly 80 micrograms per cubic metre along Kathmandu's main streets. This gas is so harmful that the WHO doesn't even have a minimum safe level for it: it is dangerous in any concentration. Kerosene worth more than Rs 1 billion is mixed with petrol and diesel every year in Nepal. Both fuels are subsidised for the rural poor, but more than 70 percent of the kerosene and diesel in Nepal is used by city dwellers.

MoPE blames lack of funds, which sounds disingenuous considering it could easily raise more than twice its entire budget if it levied a proposed pollution tax of Rs 0.50 per litre of petrol and diesel sold in Kathmandu.

Three years ago, the government decided to ban two-stroke vehicles, three-wheelers and commercial vehicles older than 20 years in Kathmandu. Minister Kamal Chaulagain who promised "bold steps" when he took office six months ago, says MoPE is in the "final stages" of carrying out that promise.

Three years ago, the government decided to ban two-stroke vehicles, three-wheelers and commercial vehicles older than 20 years in Kathmandu. Minister Kamal Chaulagain who promised "bold steps" when he took office six months ago, says MoPE is in the "final stages" of carrying out that promise.

The government's inability to stop adulteration is even more glaring, it has time and again buckled under the pressure of the petroleum dealers' lobby which wants to keep on adulterating petrol and diesel because it says there is no profit margin in selling it pure.

"It is clearly a case of sheer negligence and inefficiency on the government's part to resist the pressure from the lobby groups," says Bhushan Tuladhar of the pressure group, Clean Energy Nepal.

Nepal's successful experiment with emission-free electric vehicles is also in danger of unravelling. Chinese-donated trolley buses, which initially served up to 88 percent of the daily commuters in the Tripureswor-Surya Binayak route, was shut down last year after 25 years of profitable operations. The number of locally manufactured three-wheel electric vehicles (EV) have reached 600 in Kathmandu, and have become popular with commuters as well as transporters.

The National Transport Policy emphasised the promotion of environment-friendly vehicles, but once again it seems to be just lip service. New four-wheeler EVs are languishing in garages because the government has yet to approve of a six month trial period. "What are they waiting for?" asks one frustrated EV operator.

Five Indian made EVs have been held at Birganj customs since last March. Confused MoPE experts delayed the process not knowing that "battery operated" and "electric vehicles" are one and the same, and therefore entitled to unobstructed entry after paying 10 percent customs duty. Thanks to the bungling, the duty increased 10-fold, ruining the market value of EVs.

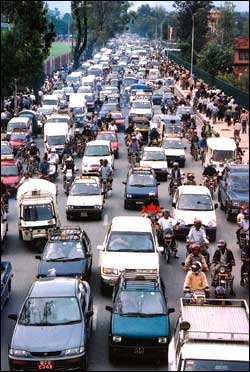

The government's failure to improve mass transit lies at the heart of Kathmandu's pollution problem. When the valley's 120,000 commuters can't find a reliable and cheap method of transportation, they will use old private buses, inefficient petrol three-wheelers, motorcycles or cars. The traffic jams they cause means the engines burn fuel less efficiently and cause more pollution.

A car emits 90 times more carbon monoxide than a bus to carry the same number of people over the same distance. A two-wheeler is marginally less at 49 percent, and three-wheeler at 60 times the emission of carbon monoxide.

The contribution of vehicles to Kathmandu's overall pollution is now overtaken by new brick kilns that scar the landscape around Bhaktapur and in Lalitpur district along the southern fringes of the valley. A construction boom in Kathmandu has fuelled the spread of the brick kilns, which bake fertile Kathmandu valley clay by burning tyres, plastic garbage and low-grade coal.

Things got so bad, and there is so much frustration with official inaction, that residents of Bhaktapur last year decided to take the law into their own hands and demolished polluting kilns near their homes. The stacks are arrayed along the southern approaches to Kathmandu airport, and air traffic controllers report poor visibility till noon, even though Kathmandu's winter fog used to clear by mid-morning.

Many flights have been re-routed, or forced to make longer and more expensive instrument approaches. Meterological data shows that the number of days per month with visibility more than eight km at noon in Kathmandu has gone down to 2, compared to 22 in 1970.

Kathmandu's killer kilns

In March 2002, the Industrial Development Board decided to phase out obsolete kilns from Kathmandu. They also set up a committee to inspect brick kilns and take action against illegal kilns. Well accustomed to the government's lethargy, the owners continue to operate the units. MoPE's own study shows that about 82 percent of the total suspended particulate in the Valley's air comes from these kilns.

At present 98 brick kilns are registered with the government, but activists have counted more than double that number operating illegally. The sudden boom in real estate construction encourages illegal manufacture of bricks. According to a 2001 study by Environment and Public Health Organisation (ENPHO) just about everyone living in the vicinity of a brick kiln in Bhaktapur suffers from respiratory problems.

Another study by Clean Energy Nepal last year in Bhaktapur's Jhaukhel VDC found the concentration of particulate matter in the air was three times higher in the brick kiln areas than elsewhere. "Our health and livelihood is at stake and the government is just not interested," says an angry Sunil Karki, a Bhaktapur resident who has filed a public writ in the Supreme Court to shut illegal brick kilns.

Besides being eye sores, brick kilns affect health, flight movement at the airport and also destroy soil fertility. A study last year showed that agricultural production decreased by half once the kilns exhausted the clay and moved on. (Hemlata Rai)

How Delhi did it

Residents of India's capital lobbied and won the right to breathe cleaner air.

HEMLATA RAI in NEW DELHI

Till two years ago, visitors to New Delhi used to compare the pollution in India's capital to the notoriously bad air of Mexico City. No more.

Till two years ago, visitors to New Delhi used to compare the pollution in India's capital to the notoriously bad air of Mexico City. No more.

New Delhi has transformed itself in that time from a cesspool of putrid air to a much healthier city with fresh air. "Clear and green" is just a slogan in Kathmandu, there they have actually gone and done it. And it didn't just happen overnight, the charge was led by an activist Supreme Court that acted because the government was too afraid to.

By the 1990s it was apparent that years of neglect and urbanisation had finally caught up with the city. New Delhi's lessons for Kathmandu is that judicial intervention actually works, but it also needs civil society, public pressure and media. Delhi municipality started by closing down polluting industries, brick kilns, hot mix plants and stone crushers. Then the Delhi government implemented a series of environment-friendly legislative and judicial directives including the introduction of unleaded petrol, upgrading diesel quality, enforcing mandatory testing of vehicular emission and requiring public transport vehicles to run on compressed natural gas (CNG).

Like in Delhi, the main culprits of air pollution in Kathmandu are obsolete vehicles and adulterated fuel. Nepali officials individually are appalled by the threat to public health, but always pass the buck. "The Delhi experience and what is happening here shows that the authorities will not make a move unless combined pressure compel it to do so," says Prakash Mani Sharma, a public interest lawyer and the executive director of the legal pressure group, Pro-Public.

Even though New Delhi's pollution levels are today well within permissible limits, there was opposition, even transportation strikes, by bus and taxi cartels. Factory owners and workers, carmakers, auto-rickshaw drivers and bus-owners have all locked horns with the Delhi government at one time or another.

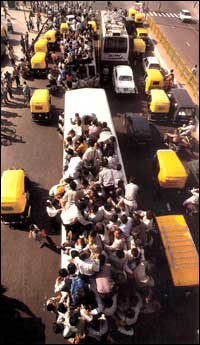

One of the biggest conflagrations was over the compulsory conversion to CNG. Government procrastination and the lackadaisical attitude of auto-rickshaw, taxi and bus operators meant that a years-old Supreme Court directive went ignored until the last moment. As a result, when finally the much-postponed deadline for conversion arrived on 31 March 2001, fuel suppliers and transporters were caught unprepared. On the first day of April, public transport ground to a halt, with only a fourth of Delhi's 12,000 buses having converted to CNG.

Tensions boiled over by 3 April with auto and taxi unions going on strike, government buses were vandalised, and rumours of sabotage did the rounds as the tanks of some CNG buses blew up. In the face of this chaos, Delhi chief minister Sheila Dikshit declared that her government was ready to "face punishment for contempt of court" but would not allow citizens to suffer.

She publicly denounced CNG as an "untried and untested" fuel and declared that its safety was "questionable". The uncertainty continued for months. Queues more than 2 km long formed at the roadside as harried auto-rickshaw and bus drivers spent nights on end trying to get their vehicles full. Only a few stations stocked the new fuel, and erratic supply meant that even at these, it would often run out.

But the supply and distribution bottlenecks have now been removed, and two years later Delhi's public transport system is much more efficient. And cleaner.

"The trick is to convince the general public that it is possible to clean the air. It will automatically create pressure for the politicians and bureaucracy to understand that environment is a part of good governance," activist Sunita Narain of the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment told us.

Studies show that between 1980 and 2000, India's GDP doubled, but in the same period vehicular pollution increased 8 times and industrial pollution was four times. The general population became victims. The World Bank estimated that air pollution kills 7,500 people annually in Delhi.

Another World Bank study for Kathmandu Valley in 1996 calculated that the monetary impact (through deaths and sickness) was Rs 200 million per year-excluding long-term impact on tourism and the effect of leaded emissions on intelligence of children. Considering that pollution levels are today several times higher, the toll would also be much higher.