A month after the ceasefire was declared, the arrival of spring cloaks this blood-soaked land in new flowers of hope. The season blurs evidence of the seven-year insurgency as we walk from Salyan and Rukum to Rolpa. Rhod-odendrons burst red flowers all along the rugged trail from Thawang to Uwa in Rolpa. In western Rukum, fields of dukku, flowering radishes, undulate in the gentle breeze. Peach blossoms confetti the paths of Rukumkot.

The evidence of war is only apparent when we reach human habitation. In the villages, the people who suffered are still sullen with memory. They distrust strangers like us who come asking questions. They talk guardedly at first, but the words spill out once they begin. Their stories of helplessness have fermented into hatred, directed predominantly against state authorities. Fear is still a constant companion.

At Kholagaun, western Rukum, the house we stayed in had other visitors-\'Manjil\', a Maoist cadre since his student days, and his wife who had come home on leave. The family has three "martyrs" to the Maoist cause. In 1999 the police killed the father and eldest daughter. Last year her 19-year-old sister died in the Mangalsen attack in Achham. The 58-year-old mother, who has been interrogated and tortured by the police, says, "I am happy my husband and two daughters died for the sake of Nepal's sons and daughters." The emptiness in her eyes makes what should have been a patriotic sentiment sound hollow.

Our arrival in the village coincided with the third 'people's council' meeting to elect new members to the district-level 'people's government'. One evening, more than 20 relatives of those killed by security forces gathered to talk with us. A 19-year-old widow who lost her husband during the attack in Jumla last November says, "I feel a strong hatred towards the enemy. I always think of how to revenge my husband's death." When asked who is her biggest enemy she gives the party line, "Everyone who belongs to state power."

Contrary to expectations, we saw very few armed Maoists en route. But at Thawang in north Rolpa armed Maoists are in full control. Members of the militia and villagers are building a road, volleyball games are organised every evening and the soldiers of the 'people's liberation army' organised meals together in a big hall. The usual greeting is a lal salaam.

In the middle of the village is the rubble of 15 houses torched by security forces when soldiers came in hot pursuit after the Mangalsen attack early last year. It wouldn't be far-fetched too say that the root of the 'people's war' lies in Thawang. This communist stronghold has been targeted by the authorities many times ever since the Panchayat era. Since 1996, 25 Thawang residents have been killed either by the army or the police, a figure that doesn't include Maoist cadre and militia from the village killed in action. "Most of them were common villagers," Pratap Roka of the Thawang 'peoples' government' tells us.

As the central leaders of the Maoists surface in faraway Kathmandu to begin peace talks with the government, who will address the deep anger of people in villages like Thawang in the midwest? How will they rehabilitate guerrillas if the ceasefire holds? Who will bring health care and education to these remote hamlets and cancel out the roots of future unrest? This is as much a challenge for the state as it is for any future local Maoist administrator.

Most villagers here have no illusions about the peace talks. "The ceasefire is just a breather. The battle will continue. We are demanding the election of a constituent assembly just to stop more bloodshed. It's not our final aim," a platoon commissar in Rukumkot tells us. Santosh Budha is a Thawang-born Maoist leader, and he adds: "The army should be dissolved and a national army under the control of the parliament should be formed." But if the central leadership has a clear plan for the future, it is not clear from talking to people here what it is.

The guerrillas are reluctant to give up their arms. "If the talks break down, we will fight again to the last," says a 23-year-old militia member in Thawang. Sitting in the sunshine under a peach tree in Kholagaun, it is clear that a peace agreement in Kathmandu will not bring an end to conflict in these rugged mountains of mid-western Nepal. A young woman says, "I am very afraid that the talks might be unsuccessful like the last time. In that case, we have only two options: run away from this village or die."

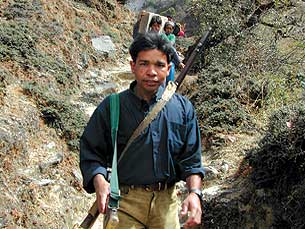

We saw only a few armed Maoists on our week-long trek from Karibot bazar in Salyan to Thawang in Rolpa. This group agreed to pose in uniform, but with masks.

Thawang is different from any other village. Security forces that stayed here a month-and-a-half in March last year set fire to the 15 houses in the village centre. Many residents fled: some went to work in foreign countries and others to live in their goth in summer pastures.

Santosh Budha, a member of the central committee member and the \'United Revolutionary People's Council\' gives a lal salaam at a mass meeting in Chaurjahari. A former high school teacher and a Magar leader born in Thawang, Budha said in his speech, "Some foreign forces are trying to benefit from the political situation in Nepal. It is possible that our main enemy might not be the Royal Nepali Army but these forces. In that case, we may have a situation where the two armies could work together."

Thousands of people gathered at this mass meeting organised by Maoists at Chaurjahari on 3 March. Twenty-five members of the newly elected United District Council of Rukum were introduced to the gathering. Celebrations lasted till 3AM and the Maoists put up a play. The main theme revolved around "the families of the Royal Nepali Army and the People's Army" and tried to show how these two armies can work together for the sake of the nation (above, right). The newly elected council was is the third after the first \'people's government\' was declared in this district two years ago. "The term of the district council is actually two years. But elections are being held every year so we can establish power more quickly," says Sharun Bantha Magar, the newly elected chief of the council. This year, for the first time, the council drew up a budget of Rs 2,300,000 for the construction of small scale hydro-electric power plants and \'people's schools\'.

We met a group of the militia who were carrying materials for rebuilding a school. Many armed Maoists were engaged in reconstructing infrastructure with the villagers in Thawang. The declaration of the ceasefire has seen many of them return home for a few days.

These ruins used to be the Rukumkot area police office, built on top of a hill as a secure fort. In April 2001 Maoists raided the station leaving 40 dead-32 were policemen. "We attacked to make the Zonal Bandh a success. It was a full moon night and the steep terrain made it really difficult to fight but they surrendered half an hour after we started the assault," recalls platoon commissar Rabi. After this attack, many police stations in Rukum and neighbouring districts were evacuated.

(Kiyoko Ogura is a Kathmandu-based Japanese journalist.)