Fifty years after the historic first ascent, climbers from around the world are taking part in what will likely become the most highly publicised climbing season to date on Mt Everest.

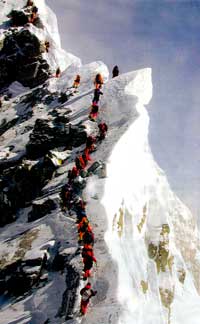

Fifty years after the historic first ascent, climbers from around the world are taking part in what will likely become the most highly publicised climbing season to date on Mt Everest. This spring, climbers will commemorate past glories and vie to claim new ones, while the rest of us sit back and cringe at the mountain's ever-increasing popularity. However, criticising Everest has become far too easy. It's old, tired, and played out. Yet, we, the public, consistently return to the world's highest mountain from the comfort of our armchairs, to critique, lament, and share in a collective nostalgia for a time long before the commercialisation and commodification transformed Everest into, what climber/scholar Stephen Slemon described: "a mainstreet, a traffic jam, a ship-of-fools party on the rooftop of the world." We lay blame all-to-easily on the commercial guided expeditions-those run by trained professionals who each season lead legions of summit-seekers up Everest's two well-blazed "yak-routes"-yet, it is ourselves who have become the Everest junkies. We buy the books, the magazines, and tune into the pop-smut high-altitude reality TV shows. Popular imagination has defiled Everest, plain-and-simple. As we count down the days to the highly anticipated golden-jubilee season that marks the famous first ascent, the inescapable Everest hoopla will rise to record heights, feeding a public consumption ravenous with summit fever, propagating a circus that began long before Everest was ever "guided".

Contrary to popular myth, commercial climbing did not begin with the emergence of the adventure tourism industry in the 1980s, nor did it begin with Dick Bass, the wealthy 55-year-old Texan, who became the first guided client to top out on the Big E, and consequently, the first to summit the highest mountain on each of the seven continents. Commercial or guided climbing is as old as the sport itself, its origins found within the European Alps in the mid-1800s, as early British explorers typically hired local villagers as guides.

It was within this period that "Mt Everest" came into being-that is, the precise moment when in 1852, in a small office in Calcutta, members of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India calculated the height of the mountain to be 8,842m, making it the highest mountain in the world. After an American bagged North Pole in 1909 and a Norwegian the South in 1911, the race began for the so-called "Third Pole", the Everest, described as "the most coveted object in the realm of terrestrial exploration".

Making the first ascent of Everest was of paramount importance to the British Empire and a preoccupation that lasted nearly half a century. After thirty-two years, and eight attempts, Britain finally claimed the first successful ascent in 1953, and the story is well known. On 29 May, Edmund Hillary from New Zealand, and Tenzing Norgay, an expedition Sherpa from Darjeeling, ascended the final slopes becoming the first men to stand atop Everest. Between the two, they laid claim to five nationalities-Indian, Nepali, Tibetan, British and New Zealander, and yet, Everest "belonged" to England and continued to play a symbolic role within a shrinking empire. News of the "timely" triumph rang through the streets of Britain as cheering patriotic crowds thronged for young Queen Elizabeth's coronation, ushering in the New Elizabethan Age and better times for England.

To beleaguer the point, Everest is, and always has been, the focal point for "conquest". From the colonial act of naming the mountain after India's British Surveyor General, Sir George Everest, to modern day record fiascoes displaying classic "me-firstism", a successful ascent has always carried social currency. Furthermore, to blame the present-day Everest circus on commercial climbing expeditions is to blatantly ignore the mountain's coloured history. Such claims are also ignorant of the fact that each year multiple mountain rescues take place on Everest, where skilled commercial guides are bringing down independent climbers, who, with limited experience and without the services of professional guides, put themselves, and those who end up saving them, in great jeopardy. In the end, the commercial clients lose out, as their guides more-frequently-than-not are becoming involved in dangerous mountain rescues high in the death zone. This is the reality of Everest.

Personally, I will not begrudge the individual who has a dream that is allowed to come true. We all have our own personal quests for adventure. My only hope is that we all approach these quests with care and responsibility. In the meantime, there is solace in the words of Bill Tilman, the eminent mountaineer and mountain explorer, who said: "Let us count our blessings-I mean the thousands of peaks, climbed and unclimbed, of every size, shape and order of difficulty, where each of us may find our own unattainable Mount Everest."

(Zac Robinson is doing a PhD on paradigmatic moments in Canadian mountaineering from the University of Alberta.)