It has been 40 years since the government in Kathmandu launched a special development package for the remote Karnali region of northwestern Nepal. The idea was to stop the influence of Maoists in China, and there was ready financial and technical help from India and the United States.

It has been 40 years since the government in Kathmandu launched a special development package for the remote Karnali region of northwestern Nepal. The idea was to stop the influence of Maoists in China, and there was ready financial and technical help from India and the United States.

Today, the tables are turned. The Maoists are on the Nepali side. And northwest Nepal is as underdeveloped and more dependent on the outside than ever before.

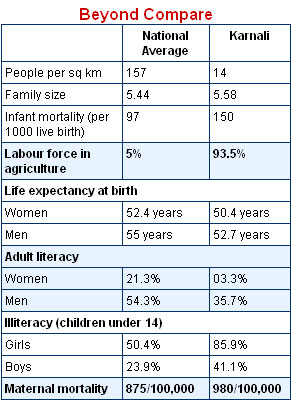

The original idea in setting up the Remote Area Development Committee was a recognition of the Karnali's remoteness, and the catching up it needed to do with the rest of Nepal. The infant mortality rate in Mugu, Humla, Jumla is almost double the national average, only three out of a 100 women are literate, and life expectancy at birth is only 40 years. Poverty is higher here than anywhere else, with per capita income only two-third of Nepalis in other parts of the country earn.

Geographer and former minister Harka Gurung remembers visiting the districts of the Karnali basin nearly 40 years ago when he was vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission (NPC). "The only achivement has been that now the people of the Karnali know what needs to be done, and are willing to get it done," he says. But they need help from the centre.

Development experts who had gathered in Jumla two weeks ago for a seminar on the development of the Karnali say it is the historical lack of representation from the region that resulted in Kathmandu's chronic neglect of the region. "Stronger political lobbying and more focused development targets only can make the region more visible in the country's development map," says Shankar Sharma, the current vice-chairman of NPC.

Mohan Baniya, the DDC chairman of Mugu agrees that the government in faraway Kathmandu has ignored the feeble voice of this remote district for too long. "People's desire for change is our biggest resource," Baniya told us.

It is not only physically that Karnali is removed from Kathmandu. There is a psychological distance as well. It costs more to fly to Jumla from Kathmandu than to fly to New Delhi. Kathmandu's attention also seems to be more focused on what happens to Bhutani Nepalis than Nepalis of the Karnali. For decades, people here have been resigned to this apathy, and got used to not expect anything from the centre.

It is not only physically that Karnali is removed from Kathmandu. There is a psychological distance as well. It costs more to fly to Jumla from Kathmandu than to fly to New Delhi. Kathmandu's attention also seems to be more focused on what happens to Bhutani Nepalis than Nepalis of the Karnali. For decades, people here have been resigned to this apathy, and got used to not expect anything from the centre.

This void has been exacerbated by the Maoist insurgency which has further isolated the five Karnali districts from the rest of the country. Telephone and postal services destroyed during the insurgency have still not been rebuilt. Airports, the only way in and out, have been destroyed and airlines are refusing to fly until security is guaranteed.

Jumlis who want to fly down to Nepalganj have to call relatives in Kathmandu through VSAT phones to book them a seat. In many other districts, Royal Nepal Airlines flights sell tickets after the flight takes off, like in a bus, because the airlines doesn't have an office.

Those who have never been able to afford to fly are also hampered. They have to pass a gauntlet of hostile Maoist and security forces checkpoints with permits required to travel anywhere. Three of the mule trail bridges joining Humla and Mugu to the south have been destroyed by Maoists, and this requires detours sometimes lasting five days. It is a two-day walk from Kalikot and eight-day walk from Humla for anyone to needing to attend the zonal appellate court in Jumla.

"This region has been doubly victimised, by the state that ignored our development needs and recently by an insurgency that destroyed whatever little infrastructure we had," says Tula Ram Bista of Kalikot DDC.

Now, political and development leaders here believe the solutions can come from the people of the Karnali themselves. At the the Karnali Conference in Khalanga they demanded autonomy to decide their own development priorities and how they want to spend their budget.

Former NPC head, Mohan Man Sainju, even proposed at the seminar that an autonomous planning commission be created for the region. Kathmandu doesn't seem to know, or care, about the realities on the ground here. The system of budget allocation and the delineation of fiscal years, for example, contradicts the seasonal variations here, when winter closes up the high passes with snow and the monsoons are late and erratic. The fiscal year that starts in July allows only limited time to carry out development activities, and most of the money has to be sent back to Kathmandu unspent.  Since the national budget is allocated on the basis of population and constituencies, Karnali gets too little to carry out development activities in the large areas it covers. The five districts of Jumla, Humla, Kalikot, Mugu and Dolpa cover almost 15 percent of Nepal's soil, but is home for only 1.3 percent of the population. Population density here is only 14 people per sq km against 157 per sq km national average.

Since the national budget is allocated on the basis of population and constituencies, Karnali gets too little to carry out development activities in the large areas it covers. The five districts of Jumla, Humla, Kalikot, Mugu and Dolpa cover almost 15 percent of Nepal's soil, but is home for only 1.3 percent of the population. Population density here is only 14 people per sq km against 157 per sq km national average.

"Budget allocation should be based on remoteness and geographical area than based on constituency like at present," says Dilli Bahadur Mahat former parliamentarian from Jumla.

The political leadership here is particularly unhappy about misplaced priorities and scattered budgets. The central government has been providing food subsidies to Karnali for the past 30 years without ever considering alternatives like investments in local agriculture. The Talcha airfield in Mugu was prioritised as a lifeline for the district, but it took 20 years for it to be completed and even now there have only been test flights.

Kathmandu-centric development plans are also the reason why the Karnali is still Nepal's only roadless region. It has been easier to build a road to connect Simikot to the Tibet border than to get a road to Jumla from the south. Kathmandu has always taken it as a given that the hill districts should be linked to markets in the tarai, ignoring the proximity and the markets in China.

The inaccessibility affects every facet of life: health care, education, social welfare, tourism and development plans. Jumla health posts didn't get their quota of medicines last year. Despite the complete disinterest shown by tourism promoters in Kathmandu, locals got together to hold the Rara festival two years ago, and private companies are taking trekkers and pilgrims to Mansarovar through Simikot. Karnali's potential for fruits, nuts, herbs all lie wasted.

"We have been wrongly portrayed as failed communities, and this had given us an inferiority complex in the past," says Jivan Bahadur Shahi, the charismatic leader of the Humla DDC. "No more. Now we are going to take our destiny in our own hands."