PRAVEEN MAHARJAN |

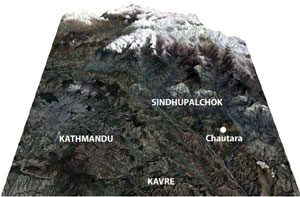

Sindhupalchok may be only 100km from the capital, but subsistence farmers here may as well be in remote farwestern Nepal. Maize farmers couldn't be bothered about the political stalemate in Kathmandu, they are more worried about their dying crops.

For 55-year-old Dhanmaya Tamang and her family in Harekolpata village, a weak monsoon has hit their only income source. "At least we had hopes from the gods. But they have also abandoned us this year," Dhanmaya said.

Usually by July each household has 200 to 400 kg of maize depending on farm size, enough to feed the family and bring in extra cash. This time, it's not even 20 kg, barely enough to last a week.

The Central Region, which includes Sindhupalchok District, fared well in last year's July-September harvest, seeing a 16 per cent growth in both rice and maize cultivation, according to the World Food Programme (WFP). This year, dozens of families in Harekolpata are planning to send their children over the mountain to Bhaktapur to find work.

"We have no choice but to ask them to leave school this year," said 40-year-old farmer Kajiman Tamang, father of two sons. The destitution so close to Kathmandu is a result of government neglect, the war and the lack of local elections for the past 15 years.

GOOGLE EARTH |

For each of Nepal's 3,900 VDCs, there is supposed to be 10 elected officials plus a government-appointed clerk. But since the last local election in 1997, there has only been the one clerk overseeing village governance.

Each DDC contains a chairman from each of the 75 VDCs in a district. They too have been operating with one clerk for the past 15 years. The delivery of a new constitution would have decentralised governance under a federal system, but that has been indefinitely postponed.

"Nothing has changed for us. We don't even have drinking water," said Sita Tamang, a 35-year-old mother of three whom she cannot afford to send to state school. Even without school fees, she still needs to find money for clothes and school supplies. Unsafe drinking water contributes to the deaths of some 13,000 children in Nepal under five annually, according to UNICEF.

"If these politicians come again asking for votes, I will shut my door in their faces," said Sita angrily recalling how during the 2008 CA elections, local political candidates promised to bring drinking water, road, schools and irrigation projects. They never returned after the elections.

NARESH NEWAR/IRIN ABANDONED FARMERS: Families in Sindhupalchok bemoan the lack of local governance since 1997 and subsequent lack of government investment in irrigation |

Sindhupalchok has been classified a 'food insecure' district by the Ministry of Agriculture - where people do not have access to enough food to keep them healthy - but with unpredictable rains even the more productive farms will be at risk, according to the government's District Agricultural Office in Chautara.

"The only way to improve our farms without waiting for the rain is irrigation. The central government has promised it for so many years, but nothing has happened," said Jitman Tamang, 40, whose half hectare of maize plants shrivelled with the late rains.

Less than half of Nepal's cultivable land is irrigated. Rural Nepalis when asked what their village needed the most used to say "roads", but as the road network spreads, they now say "irrigation".

Meanwhile, 600km away in the western Tarai district of Kailali, a region known for its relative agricultural productivity, farmer Kul Bahadar Shahi, 53, said he remembered when officials came from the land survey department 16 years ago. "Since then no one has come back. No one is really listening. Politicians take care of their own VDC."

When asked about his elected representative in the recently dissolved national CA, he said: "Our leader had a low profile and was not much help."

IRIN

www.irinnews.org

See also:

All politics is local

Seeds of wrath

|

The rice planting season was supposed to officially begin two weeks ago, but many farmers have still not planted paddy seedlings. A weak monsoon and a critical lack of chemical fertilisers have kept many terrace farms fallow this season.

The state supplies only 150,000 metric tons of chemical fertilisers at subsidised rates every year, but the estimated annual demand is more than 700,000 metric tons. In addition, the government's cheap fertiliser never arrives in time for the planting season, and farmers are forced to buy smuggled fertiliser from India in the black market. A staggering

80 per cent of the fertiliser used in Nepal is smuggled across the border from India.

This year, farmers have nearly given up hope, and by the time the fertiliser arrives they know it will be too little too late. And with police getting strict at the border, even the smuggled fertiliser supplies have dried up and when they are available they are too expensive.

"The Agricultural Inputs Company cannot fulfil the demand because of lack of funds for subsidies. The amount it imports suffers from anomalies in the tender system, the only short-term solution is to increase imports," says Hari Dahal, spokesman for the Ministry of Agriculture.

Instead of selling fertiliser at the Import Parity Price as agreed between India and Nepal, some suppliers are demanding a 30 per cent markup on the Maximum Retail Price for each ton. The government does not blacklist these companies nor does it order more, hence the chronic shortage.

Farmers who queue up all day say there is plenty of fertiliser being hoarded and sold at exorbitant prices. Most are convinced government officials are in cahoots with smugglers and merchants, which is why they don't want to stop the black market trade. Poor governance and instability have contributed to the crisis.

"After two consecutive years of surplus, Nepal's food security and revenue from grain harvests are bound to take a hit this year," says Surya Prasad Pandey, who worked at the Nepal Agricultural Research Council for 30 years. "There is a growing market within South Asia for artificial fertiliser. So if countries like Nepal, India, and Bangladesh worked together and started multi-national ventures, they would not only meet their yearly domestic demand, but also earn profit."

Sunir Pandey