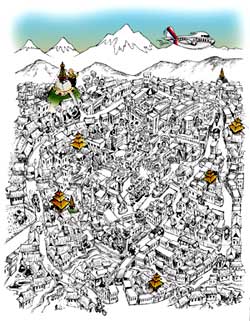

Kathmandu Valley's precious architectural heritage has been in danger ever since urban sprawl intruded upon its sacred spaces.

Kathmandu Valley's precious architectural heritage has been in danger ever since urban sprawl intruded upon its sacred spaces.

The encroachment is horizontal as the city spreads and overwhelms historical sites, and also vertical as new buildings defy height limits to dwarf temples and bahals. Although there has been a renaissance of traditional architecture in parts of Patan and Bhaktapur, the general trend is still one of erosion of Kathmandu's unique urbanscape.

The Valley was recognised as a World Heritage Site in 1979 by Unesco (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation) and it set aside seven sites: the three Durbar Squares at Hanuman Dhoka, Mangal Bazar and Bhaktapur, the stupas of Boudha and Swoyambhu and the temples of Pashupati and Changu Narayan. Outside the Valley, Unesco also declared Lumbini a sacred site that needed protection.

Despite warnings, however, migration pressure and the effects of modernisation are just too relentless for government conservation agencies and the municipality to stop the erosion of Kathmandu Valley's architectural heritage. Saving Kathmandu's heritage needs more than just enforcing existing zoning laws and building parameters. It needs a revival of the ancient guthis and a new consciousness among individuals to value their heritage.

As a warning, Unesco last year put Kathmandu Valley's monument zones on the 'endangered list', which was a major embarrassment for the government. Now, it looks like Lumbini may follow suit for unchecked construction around the Maya Debi temple.

Being de-listed from the bill of Unesco's World Heritage Sites could be a disaster for Nepal's tourism industry. And even though officials involved in conservation have been sounding the alarm bells, inappropriate construction is still causing problems. Nepal's oldest Buddhist sites, the 2,500-year-old Ashoka chaityas in Patan, have been obliterated by surrounding buildings. An overhead bridge is coming up in front of the Pulchok stupa, built by the very municipality that is supposed to conserve heritage and a new building is under construction near the Lagankhel stupa.

"Unesco has reason to be concerned and warn that they will de-list us when they see such construction," says Keshab Jha, who served as ambassador in Paris and represented Nepal at Unesco.

In 1992, Unesco gave the government a 55-point recommendation that included pedestrianisation of the city core, removing electricity transformers and enforcing vertical limits on construction. "In a recent review, we found that 90 percent of the recommendations have been followed," says Ukesh Raj Bhuju of the Nepal Heritage Society. "But construction around the heritage sites remains the main challenge."

In 1992, Unesco gave the government a 55-point recommendation that included pedestrianisation of the city core, removing electricity transformers and enforcing vertical limits on construction. "In a recent review, we found that 90 percent of the recommendations have been followed," says Ukesh Raj Bhuju of the Nepal Heritage Society. "But construction around the heritage sites remains the main challenge."

But it is not just the government that is to blame. Unesco experts have often come up with contradictory statements and there has been a tendency to put down Nepali expertise. When the Pratapur Temple on Swoyambhu collapsed last year, a Unesco expert wrote back to Paris saying he doubted that the Nepalis could rebuild it, yet it was rebuilt within a year with local resources.

Lumbini is a prime example where Unesco experts have come up with contradictory and confusing recommendations. But the nativity site itelf could have been done with more sensitivity.

After the excavation at the Maya Debi temple site was finished, plans to restore the temple got bogged down in design disputes between experts for eight years. Officials say a series of Unesco experts gave different and baffling recommendations. The Japanese Buddhist Federation proposed a design which was not accepted. Then came the government's design, which was prepared after holding public hearings. But Unesco had reservations about this design as well.

What followed was series of recommendations from Unesco experts. The first recommended that the structure should be partially roofed. The next suggested the excavation site should be open-air. The third, which happened to be the same expert Unesco had sent first, had a different recommendation and opted for a roofed structure. This coincided with what the government had in mind, so construction went ahead. By the time the structure was ready, it pretty much resembled the Maya Debi temple that had been demolished. But then word came from Paris that Unesco was not happy with it.

"Yes, Unesco was displeased with the way the temple was built," said Junko Ohashi, an official at the World Heritage Centre, Paris.

Two more Unesco experts were sent to evaluate the temple complex, but left without making any recommendations. By this point, relations between the Department of Archeology (DoA) and Unesco had soured. At the 28th session of the World Heritage Committee in China last June, officials recall, it finally became known that World Heritage Centre, which acts as the secretariat of Unesco, had not forwarded the design of the new temple to the World Heritage Committee. The DoA says it sent the design through Unesco's Kathmandu office, but the World Heritage Committee was displeased and under the impression that Nepal had rebuilt the temple without its approval.

Two more Unesco experts were sent to evaluate the temple complex, but left without making any recommendations. By this point, relations between the Department of Archeology (DoA) and Unesco had soured. At the 28th session of the World Heritage Committee in China last June, officials recall, it finally became known that World Heritage Centre, which acts as the secretariat of Unesco, had not forwarded the design of the new temple to the World Heritage Committee. The DoA says it sent the design through Unesco's Kathmandu office, but the World Heritage Committee was displeased and under the impression that Nepal had rebuilt the temple without its approval.

When we put this to Unesco officials in Paris, Ohashi replied: There were some misunderstandings regarding the communication process in the past.

Some of these misunderstandings are said to have been cleared up in China last year, and the government proposed that Unesco employ an international expert to be stationed in Nepal who could understand things better. "We convinced them that expert recommendations varied and created confusion. They have agreed to the idea of a permanent expert," DoA Director General Kosh Prasad Acharya told us.

For Lumbini, Ohashi says there will be a local technical working team established, with advise from an international expert who has good knowledge of Buddhist sacred sites.

Two Unesco consultants visited the Lumbini site last May and made recommendations for corrective measures on the new Maya Debi construction. "We have agreed to the points and there are almost no disagreements now," Acharya says.

Independent experts, however, say that there are still serious differences. "Some committee members indicated that possibility during the side meetings at the 28th session of the committee in China," says Jha.

Most conservationists agree that rather than blame-throwing, Unesco and Nepali officials should sit down and draw up a concrete plan of action on how to implement existing laws so Lumbini and Kathmandu Valley are not de-listed. Said one expert, who declined to be named: "The problem is not

that we don't have ideas, it is that we can't seem to enforce them."