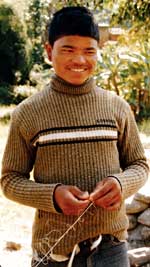

Madhab Nepali is a 28-year-old Dalit teacher whose students at the Mahendrodaya High School in Sindhupalchok's Pati Danda are from various castes and creeds. But he has never been allowed into local tea shops.

Madhab Nepali is a 28-year-old Dalit teacher whose students at the Mahendrodaya High School in Sindhupalchok's Pati Danda are from various castes and creeds. But he has never been allowed into local tea shops. "I don't even try to enter because I'd probably be thrown out," says Madhab, recalling an incident six years ago when a friend was beaten up for defying the social practice of Dalits not being allowed into eating places. But what pains Madhab even more is that there is discrimination even within Dalit society, where some 'untouchables' regard themselves as more 'touchable' than others in their community.

Madhab is about to complete his B Ed degree and is aware that the law of the land treats all citizens equally. Like many other educated Dalits, he knows that the constitution guarantees no person shall, on the basis of caste, be discriminated against as an untouchable, be denied access to any public place or be deprived of the use of public utilities. Still, he does not defy residual social exclusion. "It would just provoke conflict in society," he reasons.

Bishnu Maya Sarki is in her 50s and explains the stark reality of Nepali village life. "We have been dominated, we are poor, we are not educated, we are helpless. We aren't even confident enough to speak for ourselves. How can anyone fight injustice on an empty stomach?" she asks. But what makes it worse, says Bishnu Maya, is that Dalits are not united and rues: "If we were, maybe things would be different."

Here in the mountains north of Kathmandu Valley, despite education and media campaigns against untouchability, Dalits are still not allowed to enter teashops, restaurants and kitchens of families higher up in the caste ladder. They are discriminated at the public tap: the high caste families fill their taps first. "Even if we touch their gagro, they regard it as being defiled," explains Nepali.

Paradoxes abound. Dogs roam freely inside the houses of high caste families, but Dalits aren't allowed in. If Dalits do have a meal inside a high caste home, the family member throws bits of cow dung at the spot where they sat to purify it. "It is humiliating, how can cow dung be purer than human beings?" asks Harka Sarki.

Sadly, the social discrimination prevalent in mainstream society is reflected within Dalit society as well. Here, as in other parts of the country, some Dalits see themselves as higher in the caste hierarchy than others. The oppressed, in a desperate attempt to secure social status, sometimes turn oppressors.

Sadly, the social discrimination prevalent in mainstream society is reflected within Dalit society as well. Here, as in other parts of the country, some Dalits see themselves as higher in the caste hierarchy than others. The oppressed, in a desperate attempt to secure social status, sometimes turn oppressors. Madhab Nepali explains that some Kamis and Sarkis consider themselves higher in status than, for instance, Damais, who are not allowed to enter their kitchens. There are restrictions in marriage between Damais and Kamis. "In short, some Dalits impose the same set of discriminatory practices on other Dalits," Madhab tells us, shaking his head.

Dalit leaders say their community can't be blamed for such lingering internal discrimination. Since they grew up in an environment where discriminatory practices were normal, they follow the same tradition even though in their hearts they know it is wrong.

But 49-year-old Arjun Sarki, says the winds of change are blowing away the old practices. "Times are changing, the younger generation is more open and flexible," he says. The local community runs adult literacy classes in Sarki's house which people from all castes attend. "There is no restriction, there is no discrimination," he says.

Madhab Nepali agrees. "People from supposedly higher castes would invite me over, if it wasn't for their rigid parents," he says. "There is a long way to go but change is coming."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Majhis lose their livelihood

Conventional wisdom has it that roads bring development. But here on the banks of the Sun Kosi, at the juntion of the Arniko and Jiri Highways, fisherfolk of the Majhi community still struggle to survive.

Conventional wisdom has it that roads bring development. But here on the banks of the Sun Kosi, at the juntion of the Arniko and Jiri Highways, fisherfolk of the Majhi community still struggle to survive. There is less and less fish in the river, the Majhi don't own any land, and although the two highways are at their doorsteps, it hasn't made a difference to the Majhis of Khadichaur in Sindhupalchok. So the community takes odd jobs as farm hands and restaurant helpers.

But not all Majhis have given up their traditional occupation. One member from a family, usually a young man, will still fish in the river while relatives are away working in the city. "Fishing is tedious and hard and doesn't give you much in return," says Dhan Bahadur Majhi,19, readying the line that he will leave in the river overnight (see pic). Usually he catches a kg of fish, which he can sell for about Rs 30.

These days, Majhis are not the only fishers in the Sun Kosi. "Chettris, Kamis, Paharis, Newars everybody fishes nowadays," says Dhan Bahadur, adding that many are illegally killing fish by electric shock and this has reduced the catch in the Sun Kosi.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dalit conference

The International Conference Against Caste Discrimination is being held 29 November-1 December in Kathmandu. Organised by the Dalit NGO Federation (DNF) and International Dalit Solidarity Network, it is the first of its kind. According to DNF, the participants of this event are from countries where caste discrimination is still prevalent.