|

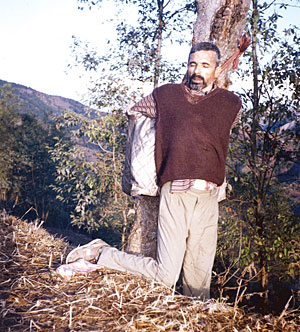

Muktinath Adhikari, headmaster and Grade 10 teacher at Padmini Sanskrit Higher Secondary School in Lamjung, was teaching a Science class when the Maoists came and took him away in January 2002. That afternoon, he was taken to a hill overlooking the village, tied to a tree with his scarf and shot through the head. According to the Maoists, he was an informant, who hadn't donated the required 25 per cent of his teacher's Dasain bonus to their cause.

It has been exactly eight years since Muktinath was murdered. His son Suman has since moved the family to Kathmandu. Suman's mother has been ill since his father's death and doesn't want to go back to Lamjung. Whenever Suman visits his village, he feels uncomfortable in his own house.

Suman and his family have never wanted to know who killed Muktinath. What Suman does want to know is why his father, a sincere, hardworking man who had never hurt a soul in his short life, was accused of being an informer and killed so brutally. For eight years Suman has gone from one government office to another, to the Peace Ministry, to every Prime Minister who has taken office. They all sympathise, but no one has done anything. Now Suman doesn't even know where to go to, who is accountable, or how to go about trying to get justice.

It's not money that the Adhikari family wants. Muktinath made sure that his children got a good education. Both Suman and his brother have jobs that can support the family. "What is reparation? Can any amount of money bring back my father?" Suman asks. He wants closure - acknowledgement from those responsible that what happened to Muktinath was wrong. He wants the party responsible for murdering his father to ask for forgiveness from his mother and his family. "My father shunned violence, he was not an informer, that is not how a good person should be remembered," says Suman.

Whenever the issue of repatriation and reconciliation is raised, however, there are always those who say that this is not the right time to talk about it because it will hamper the peace process. The victims who are awaiting justice are also told the same thing when they approach the government. But how can a peace process be successful when thousands are still traumatised by what happened during the war?

The families of the war victims of both sides want to know how and why their loved ones were killed and where the disappeared are so that they can move on. The most unfortunate thing is that the government has no data on the number of people who were killed or disappeared during the war. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Disappearance Commission are in limbo. The victims do not know where to go to have their cases heard because no one wants to be accountable.

Media, civil society and non-governmental organisations can lobby and provide support to these victims, but the nature of reconciliation is such that government itself has to be involved. Simply providing money won't do the job, either - war orphans should be given scholarships and widows should be taught skills they can use to get back on their feet.

The government needs to come up with a comprehensive plan as a matter of priority for the peace process. The victims are in pain, some of them are very angry, and they will not wait forever.