CHONG ZI LIANG |

Then he proceeds to pierce the balloon with the needle without making it burst. The children gasp, and then erupt into applause. "But if they can't live together," the white-bearded Verner continues, "this is what will happen." He pokes the needle into the balloon, which bursts with a loud bang.

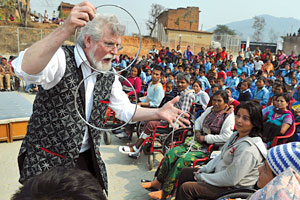

Verner and his wife, Janet Fredricks have been touring the world, performing magic for refugee children and at orphanages for the past eight years. They have performed in Ethiopia, Sudan, Guatemala, in the slums of Mumbai and are in Nepal for the first time.

Verner set up Magicians Without Borders after performing in Bosnia after the war. After being entertained with magic, some Roma refugees wanted him to multiply their gold coins, others wanted him to produce US visas out of thin air.

"We found out that despite the hopelessness of their situation, magic gives people hope," says Verner, "it shows children anything is possible."

This week, Tom and Janet are performing magic shows at the eight Bhutani refugee camps in Jhapa and at orphanages in Pokhara. Despite performing to audiences who do not speak English, Verner feels they do not have any problems understanding the show. "The language of magic is universal," he explains.

After Verner began touring the world, Janet joined the show as a mime for comic relief. "I didn't want to be left all alone at home," she says, "performing all over the world opens your heart when you see children in such difficulty smile and laugh."

Magicians without Borders is based in Vermont in the United States where Verner is a professor at Burlington College and Fredricks is an artist. It is supported entirely by small individual grants.

Their 45-minute show consists of simple magic tricks: pulling flowers from behind peoples' ears, rejoining a rope that has been cut, making sponge balls disappear and multiply. Each trick brought squeals of delight from young audiences at Maiti Nepal and other orphanages in Kathmandu as well as patients at the Spinal Injury Centre in Banepa last week.

Nearing the end of the show, Verner often brings it to a close with a magic trick carrying a moral behind it.

"Sometimes, life can fall apart and bad things can happen," he tells the crowd as he tears up a white paper ribbon and swallows the pieces, "but if we work hard, life can become good again." He then pulls out an endless ribbon of rainbow coloured paper from his mouth.

But why refugees, we ask. Verner says the answer was given to him by an elderly Afghan refugee who had been living in a camp in Iran for 17 years. After his magic show, the refugee told Verner: "For 17 years, the world forgot us. Those who remembered treated us just as stomachs that needed to be fed. Thank you for treating us like human beings and feeding our minds."