The transfer of government schools to communities started modestly in 2002, and in the first year 95 schools were handed over to community management.

The transfer of government schools to communities started modestly in 2002, and in the first year 95 schools were handed over to community management.

In the second year, the program gained momentum and the total reached 1,000 and now well over 2,000 schools are under community management. That is more than 10 percent of about 21,000 government funded schools in the country. But this year, the process has slowed rather sharply. Is this another case of Nepal failing to bring a good reform to its logical conclusion?

Since last year, in many areas local Maoists seem to have warned communities not to accept the management responsibility over their own schools and where the transfer had already happened, return the responsibility to the government. Their basic argument seems to be that this transfer of schools to community management is a sly trick and that the government will abrogate its responsibility to fund these schools. Some teachers' groups seem to have also spread the same story and many communities are confused and worried.

What is really happening? The evidence does not support the notion that the government is trying to shirk its responsibility for funding primary schools. The allocation for primary education has, in fact, increased from 8.7 percent of the total budget in 2001-2 to 9.3 percent in 2005-06. Most of the schools transferred to community management have, if anything, seen an increase in funding.

Furthermore, about 2,000 additional schools that had been started by communities and had not received any government support (they used to be called 'community schools' but are now known as 'unaided schools') began to get grants to pay for one teacher in 2003 and for two teachers in 2004, and the government plans to increase this gradually so that these 'unaided schools' will eventually bebrought in line with other government funded schools. This certainly does not seem like a government that is trying to withdraw from the funding obligation for primary education.

In the meantime, the government has made good on the promise to hand over the power to hire and fire teachers to the school management committee by amending the Education Act and Regulations. It is clear that the government is serious about the idea of a public-private partnership in which it provides the financing and the community provides the management oversight of the school.

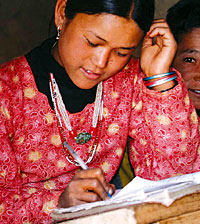

A recent survey of over 10,000 households served by 33 schools that have gone over to community management shows that the impact of this change has been phenomenal (see table).

| Indicators | Academic year 03/04 | Academic year 04/05 |

| Out-of-school primary age children | 20.4% | 8.0% |

| Out-of-school primary age girl children | 22.4% | 8.7% |

| Out-of-school primary age Dalit children | 28.9% | 1.1% |

| Primary dropout and repetition rate | 13.7% | 9.5% |

| Secondary dropout and repetition rate | 8.9% | 4.6% |

What results show is that modest performance incentives and community efforts make a powerful combination to improve provision of education dramatically and very fast. Although this survey covers a small sample, the leaders of the national network of community managed schools tell us that these results do not surprise them at all. They are consistent with what they have been seeing themselves, though their observations are not quantified.

This is great news for the education system in Nepal. I suspect the achievements are far better than anyone had expected. But, it is also encouraging for the development effort in Nepal more broadly. When the political crisis and the insurgency have made development work more challenging, there is increasing evidence and realisation that letting the communities lead the way is the smart approach to sustain development. This survey's results strongly support this idea.

Of course, community management of schools is but one example of such an approach. There is a scope for the government to expand its support for a number of other community-based programs like the Poverty Alleviation Fund, rural drinking water (through the 'Fund Board' and other programs) alternative energy development (through the Alternative Energy Promotion Center), rural electrification (through the community electrification program), and microcredit schemes (through the Rural Microfinance Development Center).

A rather unproductive game of disinformation about the true intention of the government continues and the Ministry of Education and Sports has failed thus far to counteract such a smear campaign with resoluteness. Many communities have become uncertain about the community management concept, and some observers seem to feel that this reform process is no longer working.

But many of the communities that have taken over school management are seeing impressive results. They march on and other communities that have been confused by conflicting information would do well to follow their lead.

Ken Ohashi is the World Bank Country Director for Nepal.