We as a society have so come to accept corruption as a part of life that when a businessman and ex-minister decides to come clean and make up for past sins, we dismiss him as a crackpot.

We as a society have so come to accept corruption as a part of life that when a businessman and ex-minister decides to come clean and make up for past sins, we dismiss him as a crackpot. Hari Prasad Pandey had publicly confessed through media two years ago (see 'Mea Culpa', # 92). This week, he appeared on the NTV talk show Dishanirdesh to tell Vijay Kumar Pande that since the government wasn't interested in punishing him, he was punishing himself. He is still serving a three-year self-imposed house arrest in Pokhara, and surviving on a daily prison ration of Rs 15. He has set aside Rs 25 million, roughly equivalent to the bribes he says he has given and the tax he evaded during his career, which the government can use for a good cause. The government hasn't taken him up on the offer, so he is spending the money on schemes like a scholarship program for 40 young women to get college degrees.

Hari Prasad Pandey says he didn't accept bribes when he was minister, he is just atoning for the ghoos he gave to further his business interests. Most other politicians, bureaucrats, officials and businessmen aren't as worried about bad karma. For anti-corruption watchdogs, the most difficult part is figuring out where to start. When corruption is so endemic, so accepted, and is such a given, how do you decide which crook to run after first, without making it look like political vendetta?

After a decision to investigate is made, and if you can penetrate the secretive netherworld of officialdom that leaves no paper trails, then you hit the brick wall of public apathy. This is the so-what's-new mentality, and the conspiracy of silence allows the corrupt to lie low for things to blow over, as they inevitably do. The judiciary, civil society and law-enforcement will ignore reports because they expose inadequacies and also because it means more work. The politicians will make sanctimonious noises, but they will never rock the boat and will pretend to look the other way.

If someone gets rich quick, it always means someone else gets poor fast. All corruption ultimately affects the ordinary citizen. Often, the effect is direct: a patient who dies because of fake pharmaceuticals, pedestrians who suffer chronic lung disease because officials are paid off to allow unlimited diesel car imports, politically connected borrowers who default billions from banks and endanger ordinary depositors, children who die of measles because money for the vaccines was stolen.

Then, there is the indirect effect: the high cost of electricity because past ministers were bought off by conscienceless contractors to rip the country off, an official who tried to secretly sell Nepal's geostationary orbital slot to the highest bidder, another official who gave away our fifth freedom rights to a foreign carrier for free.

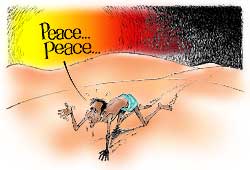

Like the garbage that lies uncollected because the municaplity is now run by unaccountable people no one elected, the stench is pretty overpowering. Only by putting into place a credible mechanism to clean up graft will we ensure long-term peace.

Where shall we start?