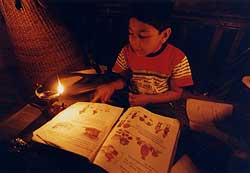

As evening falls over this small villager in southern Lalitpur, the inky darkness is broken only by the unsteady flickering of kerosene lamps and tukis. But outside, the sky above Kathmandu glows with bright city lights.

As evening falls over this small villager in southern Lalitpur, the inky darkness is broken only by the unsteady flickering of kerosene lamps and tukis. But outside, the sky above Kathmandu glows with bright city lights.

Shanti Kala Shrestha, a primary school teacher, misses the convenience of electricity that she had grown accustomed to in her home village. "It's little wonder that children in this village do so poorly in their exams," she says, motioning to the tuki. Dukachhap's lack of electricity is remarkable considering it is located across the river from Nepal's first power plant at Pharping, which will soon celebrate its 100th anniversary.

The villagers used to complain, now they are just resentful. "It is sheer negligence on the part of the government. They are happy to sit in Kathmandu with their bright lights, not one cares for small villages like ours," says Dilli Prasad Ghimire, Shrestha's neighbour. Indeed, if this is the situation for a village so close to the capital, it is easy to imagine how much worse it must be elsewhere.

Only 18 percent of Nepal's 23 million population have access to electricity. Rural areas are far down the receiving line: only six percent of people living in the hinterlands have access to electricity. With only 30,000 new connections a year, the Nepal Electricity Authority's (NEA) rate of distribution is outstripped by growing demand. Half of the 525 MW electricity available in the national grid is consumed in Kathmandu Valley alone, and the NEA spends more than 45 percent of its income on purchasing electricity from independent power producers.

Of late the buzzword in the corridors of the NEA and other government planning offices is "rural electrification". Big power-sector donors like the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, SIDA and DANIDA have shown an interest in projects and are interested in funding schemes to take power to the villages. NEA itself is keen to replicate the success of irrigation and water management sectors, by giving power generation and distribution to community users groups (CUGs) that will allow local involvement in electricity generation, distribution and even in the collection of revenues.

This new concept is expected to simplify electricity delivery into an effective and reliable method with CUGs responsible for distribution and collection of revenues. The government hopes local involvement will reduce non-technical losses, and cut operational and maintenance problems.

The vision to expand rural electrification with the help of local initiative is not a new idea. It was first envisaged in the 9th Five Year Plan but was never implemented. The NEA is determined to see it through this time. Beginning July, communities can apply for the development of power projects and/or distribution systems independently or in partnership with the public sector. The directive also plans on assigning CUGs a 10 percent share from arrears collected from defaulters, and a 25 percent from defaulted fees of blacklisted consumers.

The good news about rural electrification is that Nepalis are willing to pay for it. A United Mission to Nepal (UMN) study shows that electricity is highly valued and rural users are willing to pay as much as urban residents, even though it is three times higher than in industrialised countries. The study also found Nepali consumers who spend an average of about $9 annually on kerosene lamps lit for three hours in the evening, were prepared to pay up to 30 cents, or up to $ 1.50 per month, for every kilowatt-hour of electricity.

Senior charter accountant Ratna Sansar Shrestha is skeptical about community involvement because of the cost factor. "Even with the private sector as part of the deal, rural consumers may not get cheaper power," he says. "The NEA cannot go lower than the Rs 4 per unit that rural consumers are already charged."  There are other dangers: rural electrification has been a pork-barrel issue for politicians and is often done haphazardly. Little effort is focused on assessing whether designs and standards are appropriate for rural populations where light is the principal use and peak demand is low. "Things will not work properly unless a monitoring mechanism is put into place and is active in full capacity," warns Sridhar Devkota, of the German-funded Small Hydropower Promotion Project.

There are other dangers: rural electrification has been a pork-barrel issue for politicians and is often done haphazardly. Little effort is focused on assessing whether designs and standards are appropriate for rural populations where light is the principal use and peak demand is low. "Things will not work properly unless a monitoring mechanism is put into place and is active in full capacity," warns Sridhar Devkota, of the German-funded Small Hydropower Promotion Project.

Adopting an alternative approache in producing and distributing has yielded encouraging results at Syangja in mid-western Nepal. The Butwal Power Company distributes electricity produced from the 5 MW Andhi Khola to more than 500 consumers scattered through six villages in the district at about Rs 9,600 per connection and spent about Rs 30,000 per km in materials and labour-significantly lower than global rates of $600 per consumer and infrastructural costs of $5000 to $15,000 per km.

A UMN study shows that a 1 kV distribution system for villages with no ready access can save up to 30 percent in cost above that incurred through the use of the conventional 33 kV system. The only disadvantage would be consumer clusters that are usually very small and dispersed.

After a conference in March this year, nine cooperatives from Jhapa and groups like Ama Samuha from Kaski also came up with partnership proposals involving the government to develop power in their respective districts. In another attempt to attract local investment, NEA announced the flat buy back rates of Rs 3 and Rs 4.25 for the wet and dry seasons respectively with an annual 6 percent escalation with 1998/99 as the base year for the under 5 MW plants. This triggered a flurry of positive responses from local developers, contractors and financial institutions.

Local investment in micro-hydro power projects will bring down production costs. If the idea clicks, hydropower experts both in the private sector and the officialdom believe, rural electrification can be done even without the foreign assistance donor agencies including the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Community involvement has other direct benefits. Electronic current cutouts can replace the more expensive conventional energy meters, halving the cost of distribution. Power-based tariff can also be implemented, which eliminates the costs associated with meter reading and billing. This small alteration is especially practical for rural users who use less than 50 cents worth of electricity a month but end up paying an equal amount for billing services.

Unfortunately, the interest has yet to transform itself into concrete policies. The managing director of the NEA, Janak Lall Karmacharya, says the state-owned institution is caught in a Catch-22 situation. "Rural electrification and reduction in generation cost is our priority areas, but we also need to be more commercial oriented. Selling electricity to rural populace will not make us a profit, which is vital to increase people's access to electricity," he says.

While the bureaucrats, donors and engineers in the city debate on the right time, method and price for rural electrification, another dark night falls on the homes in Dukachhap. The tukis are lit and the children strain their eyes to finish homework.