Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies, in a final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, from those who are cold and are not clothed.

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies, in a final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, from those who are cold and are not clothed.

General Dwight D Eisenhower

One of the most crucial issues raised after the 29 January ceasefire and the issuance of the code of conduct on 13 March has been the integration of the 'people's army' with the Royal Nepali Army to transform it into a national army under civilian control. Arguments in favour of this idea are made both by the Maoists and influential politicians. The Maoists' interest in this proposal is understandable while resistance to it has been informal and based on the dilution of loyalty in the army to its supreme commander, the king. This fear may not be unfounded, but a large army could also have an adverse effect on the national interest.

The best option may be demobilisation of the insurgents and a significant reduction in the defence forces, either unilaterally or through negotiations between warring parties. Demobilisation can be achieved either by the Maoists laying down their arms in exchange for promises of genuine political reform, or a demobilisation compensation program or through total demobilisation of the Maoists guerrillas and partial demobilisation of the army within one year. A third option is bargaining for total demobilisation and the abolition of the armed forces (a la Costa Rica) however unrealisitic that may seem today.

In the third option, we are going beyond just civilian control over the military, to doing away with the military altogether. Nepal's peaceful future can be built on demobilisation, demilitarisation and democratisation. Our history is based on conquest, control and consolidation of the power of the state by the monarchy. When constitutional practices under democracy are weakened in an absence of equilibrium in civil-military relations, instability grows. Weak democracies are therefore fraught with the dangers of being overwhelmed by powerful militaries, even when constitutionally controlled by parliament.

The integration of the 'people's army' with the Royal Nepali Army can be an ominous development. It will be merely an arrangement of convenience between two hegemonic political groups, as this hegemony is presently maintained through coercion and the use of violence. Such an arrangement may serve the purpose of the survival and continuity in power of the contending groups, but not the democratic aspirations of political parties who are currently in limbo. So, here is why we need to demobilise:  . Economic Imperative: The Royal Nepali Army has grown from about 50,000 to 63,000. There is already little money to weaponise, but as the force grows the government will have to find the funds. Between 1990 and 2002, Nepal's defence budget increased from Rs1 billion to over Rs 7 billion. From 2000 there has been a doubling in arms spending and an additional Rs 5 billion was allocated after the emergency was declared. Total security expenditure for the fiscal year 2001/02 therefore was approximately Rs 18.36 billion, including Rs 7.54 billion by the Home Ministry. All this money has been diverted from social sectors: hundreds of public schools have closed, development work in rural areas abandoned.

. Economic Imperative: The Royal Nepali Army has grown from about 50,000 to 63,000. There is already little money to weaponise, but as the force grows the government will have to find the funds. Between 1990 and 2002, Nepal's defence budget increased from Rs1 billion to over Rs 7 billion. From 2000 there has been a doubling in arms spending and an additional Rs 5 billion was allocated after the emergency was declared. Total security expenditure for the fiscal year 2001/02 therefore was approximately Rs 18.36 billion, including Rs 7.54 billion by the Home Ministry. All this money has been diverted from social sectors: hundreds of public schools have closed, development work in rural areas abandoned.

. The National Question: This is not just to put the army under the command of an elected parliament, but also to examine the root cause of violence which is the failure to establish a democratic civil society. Social justice and inclusion has to be in-built with systematic a devolution of power, enhanced participation and delivery of basic services to the people. Any delay in solving these three issues could jeopardise the country's viability, which even a national army would not be able to avert.

As a progressive force, the Maoists have to understand that militarisation will entrench conservative forces. And this can only be reversed by progressive demobilistion and ultimate demilitarisation. Demobilisation can slash soaring military spending and true democratisation can transform the institutional rigidity of the armed forces to counter the Maoists as a political force.

. Peace Dividends: The first casualty of demobilisation will be the job loss of service personnel, which could be a threat to the state. Demobilisation is not easy as laying off workers. But if done carefully, it can provide an opportunity for development. A demobilised soldier can contribute to the development process. The sudden influx of people in a shrinking job market has to be managed and sustained with financial compensation, occupational and professional training, and public assistance-funded by the savings made from demobilisation. The whole process can start with first collecting weapons from the insurgents, then assuring their personal security with rehabilitation, and by providing them jobs.

. Return to Civilian Order: If violence were to be discarded as a mode of political behaviour after a future peace accord, then the armed forces will not have a political role in democratisation. Militarism has always destroyed the social space, allowing social rifts to manifest themselves. The best option for achieving social peace therefore, is not just to put an end to violent conflict through a peace agreement but also by re-integrating soldiers of fortune into civilian life. The Royal Nepali Army and the Maoist army are both made up of rural people from similar social, economic and ethnic backgrounds. The difference lies in the officers' corps. It is unlikely that the officers of the Royal Nepali Army, which is composed of the country's elite, will approve of the induction of the Maoists into their ranks. Their survival instinct could even threaten the negotiation process if the Maoists insist on this issue. Demobilisation could get around this problem.

Demobilisation must be accompanied by a move towards pacification with these intermediary steps: repatriation, compensation for victims of war, rehabilitation and national reconciliation. Delayed rehabilitation programs and the absence of economic opportunities will jeopardise pacification and lead to a surge in criminal activities. This transitional phase will require a vision for the reconstruction of the civilian order.

Demobilisation means investing in long-term peace: in creating jobs and conditions of growth. A stagnant economy and widening poverty would be the ingredients for regression. Demobilisation must be accompanied by democratisation at the political level. Unless citizens can make decisions, there will be no development, without which there is danger of renewed violence.

Because negotiations on contending and converging issues have yet to commence even after three months of the declaration of the ceasefire, the situation has again become fluid and uncertain. The Maoists are expressing concern about violations of the ceasefire, and marginalised political parties are becoming antagonistic towards the monarchy. This cannot be a permanent fixture of national life and the gradual pairing of either of these forces against the other would only weaken the societal power of the contending groups. We need to transform their divergence into convergence, and this can only happen with an unflinching commitment to democracy and a peaceful social order. Otherwise the ensuing impasse could again resurrect violence and disorder in Nepal, validating the notion that 'civil war seldom ends through negotiations'.

Despite tragedies brought about by its espousal of violence, the Maoist insurgency has brutally exposed the failure of governance in Nepal. The ceasefire has given both a moment to reflect on and reassess past failures. Negotiations should not only be confined to ideological contentions for reorganising the state, but also address the question of nation building and the dilemmas of democratisation and how to refurbish the state with representation.

The crux of the problem in Nepal presently rests on the challenges to authority and national reconstruction. The monarchy as an institutional form of authority has been tested in the past and questioned by the people once it entered the political fray. The political role of the monarchy brings up the issue of the resurgent ultra-right and ultra-left which has isolated the forces of moderation. Despite differences, the radicals are united in their goal to establish a one-party state with one-man rule using ultra-nationalism.

The process of subverting democracy has unfortunately been encouraged by the forces of moderation with their overzealous self-assertion and inability to forge a consensus against both absolute monarchism and Maoism. Both the negotiating parties are currently ignoring the legitimacy that can only be ascertained through popular consent.

To conclude, Nepal is too impoverished to afford a bloated military. The internal security role can be assigned to an armed police or paramilitary forces to prevent the army from being politicised with involvement in domestic disputes. Demobilisation should therefore be integral to the peace process not just to yield a peace dividend, but also to prevent militarisation and lay the conditions for long-term peace.

(Dhruba Kumar is Professor of Political Science at Tribhuban University.)

REJOINER by Bidur KC

In an earlier article, Dhruba Kumar had come up with the idea of slashing the number of army personnel, arguing that the country cannot afford such a big security force. His previous opinions on national security were, of course, thought provoking, but this latest argument is unjustified. His argument, based on the possibility of an increased security budget, overlooks the Royal Nepali Army's (RNA) historic contribution and immense responsibility and importance in the changing political scenario.

In an earlier article, Dhruba Kumar had come up with the idea of slashing the number of army personnel, arguing that the country cannot afford such a big security force. His previous opinions on national security were, of course, thought provoking, but this latest argument is unjustified. His argument, based on the possibility of an increased security budget, overlooks the Royal Nepali Army's (RNA) historic contribution and immense responsibility and importance in the changing political scenario.

An effective and reliable mechanism to save the country from internal and external attacks, the RNA has already tackled many crises including the Khampa rebellion. It succeeded in restoring peace, law and order to a remarkable degree after it was mobilised when the state of emergency was declared in 2001. It even succeeded in recovering weapons, cash and goods looted by Maoist rebels.

Unlike traditional security forces, the RNA deserves to be viewed as a complement to development. That is why for the past three years Maoist-affected districts have had the Integrated Security and Development Program. It aimed at stepping up socio-economic infrastructures, increasing public participation and controlling terrorist activities. The program has had positive results in Gorkha and the army still has a leading role in the project. In the near future the ISDP will be renamed the Internal Peace and Development Project and will be implemented in 16 districts. The RNA will also be involved in the National Security Council's plan to rehabilitate Maoist victims.

The geographical position of our nation is another reason to maintain the army. Given our mountainous topography, we need more soldiers to guard our borders. We cannot overlook the fact that criminals easily cross borders at unregulated points at three shared international boundaries. Most importantly, we must take note of an increasing Indian military presence to our south. The army needs to be alert to the scourge of drugs that plagues the South Asian region. Narcotics production and transportation, ethnic and religious conflicts can and must be controlled.

Analysis shows that Nepal already faces internal and external threats. Should these dangers rise, the present strength of the army, in terms of manpower, is quite low. The Former Chief of the Army Staff, Sachit Shamsher Rana, has rightly suggested that the RNA must have 125,000 personnel to be effective. The army is already implementing the concept of Corps but we need more manpower. It was because of our inadequate numbers that the RNA took so long to contain the Maoists. If more complicated problems arise in the future, it could be even more difficult. Without a doubt, the army barracks in several districts have to be strengthened.

It is wrong to say the army is required only in times of conflict. I submit that Dhruba Kumar's opinion of the army involvement in peacetime politics is faulty. During periods of peace the army mobilised resources to build roads at an expenditure cheaper than what the Road Department would have spent. Rescue work during natural disasters, conservation of national parks, control of smuggling through custom points-all these are made possible only through deployment of the army. In addition, during the insurgency the RNA has guarded important national infrastructures and telecommunication repeater stations. Lastly, the army ensures democratic practices by ensuring local and parliamentary elections proceed smoothly.

Unstable politics and weak governance could allow Nepal to become a playground for foreign powers. If the RNA is allowed to modernise, it can act as a watchdog even in these affairs. We must rid ourselves of the notion that we will be helpless in the face of foreign aggression. Instead of relegating it to a mere symbol, the RNA should be strengthened in terms of both quality and quantity.

It is necessary for the RNA to have adequate resources, means, weapons and equipment to face the challenges of the 21st century. It is just as important to gradually increase the number of personnel in keeping with the unfolding national events. This should not be called militarisation.

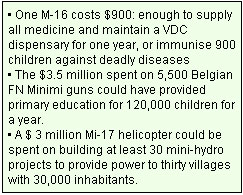

More soldiers in the army does not mean the economy will be burdened. It is a necessary expenditure to protect the nation's freedom and sovereignty. The RNA must be seen in the same light as education, health and social welfare initiatives. In his piece, Kumar has exaggerated military expenditure, arguing the money could have been better spent on medicine, education and small hydropower projects. It is of note that he failed to correctly quote even the price of an MI-16 rifle-it is $447 and not $900 as he claimed in his article.

It will be difficult to merge the Maoist militia with the RNA. The two have different opinions and dissimilar training. Co-ordinating the two will be difficult, if not impossible. Serious thought must be given to where and how the rebel army can be integrated. The RNA is the most important cornerstone of national security. Kumar's analysis is illusionary and biased.

(Bidur KC is a pseudonym.)

(Both articles have been translated from Nepali and appeared previously in Himal Khabarpatrika.)