On 22 October 2003, I was in Sapporo in Hokkaido when I heard that Govinda Mainali's appeal had been rejected by the Surpeme Court. A reporter in Tokyo called me on my cell phone for reaction, and I trembled with anger. The ruling was totally unjust. Even though the District Court acquitted Govinda, the High Court continued sloppy deliberations with the presumption of guilt to come out with an unacceptable ruling of a life sentence, overturning the acquittal.

On 22 October 2003, I was in Sapporo in Hokkaido when I heard that Govinda Mainali's appeal had been rejected by the Surpeme Court. A reporter in Tokyo called me on my cell phone for reaction, and I trembled with anger. The ruling was totally unjust. Even though the District Court acquitted Govinda, the High Court continued sloppy deliberations with the presumption of guilt to come out with an unacceptable ruling of a life sentence, overturning the acquittal.

Starting next year, a series of reforms are to be introduced in the Japanese judicial system to allow for more participation of citizens. Govinda's ruling totally goes against that trend and is a travesty of justice. After the acquittal by the District Court in 2000, Govinda should have been deported immediately for illegal overstaying, but he was re-detained. uch action is unconstitutional and the rejection of the appeal now highlights the injustice of the whole procedure.

As someone who has followed this case closely, I maintain that there has been a serious miscarriage of justice and Govinda's case throws up many questions of judicial reforms in Japan not just for foreigners, but also for Japanese citizens. It also opens questions of docile Japanese journalists who are completely taken in by the power of authority and simply pass on their information through the media.

No Japanese reporters actually went to the Maruyamacho area of Shibuya Ward, where the murder took place. No reporters, except a Nepali journalist in 2001, ever bothered to interview Govinda in the detention centre in Kosuge to hear his cries of innocence.

A song of hope

On 21 October when legal reporters, tipped off by the authorities were already writing their stories about the rejection by the Supreme Court, social activist Naomi Yoshikawa of the Justice for Govinda Group went to see Govinda. She had no idea about the Supreme Court verdict. At this time Govinda himself had not been notified of the decision.

The minute he saw Naomi, Govinda thanked her for writing out the lyrics of his favorite song in Roman letters and sending them to him. Govinda had mentioned that he liked the song 'Nada Souso ('Tears trickling down') by an Okinawan singer, Rimi Natsukawa. Naomi had started visiting Govinda in March 2003 when she accompanied Radha, Govinda's wife, to Kosuge for a brief prison visit. When Govinda mentioned the song, Naomi said, "The song sounds like it's about you and Radha, doesn't it?" She later wrote out the lyrics and sent it, adding a message that said, "I hope the two of you can see each other again soon."

Naomi and Gonvida talked about their families and their daughters. As always, Govinda was caring and considerate about others despite the stress of his incarceration. Govinda told Naomi that his elder daughter Mithila would like to be a doctor and he wants to make her dream come true. Now, there was no point dreaming any more. Naomi told me: "It's too much to bear to think that what we did that day, talking about the hopes for the future, it might have made it even harsher for him to take in the shock. Naomi Yoshikawa told Govinda "See you next week, take care," waved goodbye and left the visitor's meeting room.

On the morning of the following day, 22 October, the defense counsel and the core members of the Justice for Govinda Innocence Advocacy Group went to see Govinda after learning from the media about the decision. The moment he saw them, Govinda showed the document declaring the Supreme Court decision by putting the sheet of paper against the transparent acrylic board dividing the visitors and detainees.

The rejection seems to have been cruelly timed for Govinda's 37th birthday which was on 21 October. Govinda sobbed incessantly, and said: "The Supreme Court is a place where the brightest people in Japan are, isn't it? And that court is sending an innocent man to jail? I haven't done anything wrong, how can I spend my life there? I won't be able to see my aging parents alive in this world anymore."

I called Urmila, Govinda's elder sister, in Nepal. I had seen her in Kathmandu a few years ago. Choking back tears, she said, "When a Japanese TV reporter called me, my hands started to shake and I couldn't say anything." She called her sister-in-law, Radha, in Ilam who wept on the phone, called out Govinda's name again and again. "I felt so sorry for my gentle brother," Urmila told me. "Govinda didn't do anything wrong. God knows the truth, now, I can only pray to God."

Govinda's brother Indra still hasn't recovered from the shock.

"When we heard the sad news, all went quiet in the house, nobody said anything," he told me. "Then everyone started crying at once. I couldn't stop crying, the tears just gushed out." Govinda's 76-year-old mother and 82-year-old father, Radha and the children, all wept bitterly. Neighbours heard the crying, and thinking someone had died, went in to find out what was happening. In the ten days after the Supreme Court verdict, Govinda got more than 300 letters from friends and strangers, who wanted to cheer him up.

The evidence

Yasuko Watanabe was a senior employee of the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) by day, a prostitute by night who walked the streets of Shibuya. She disappeared on 8 March, her body was found in Room 101 of Kijyu-so apartment building in Maruyama-cho, on 19 March. In the toilet bowl of the apartment was a condom containing semen. The police determined that she was killed late during the night of 8 March and a DNA test was conducted on the semen, and this was determined to be Govinda's.

Govinda admitted to having sexual intercourse with Watanabe in that room on 28 February. But the police insisted that it happened on 8 March. This became the most critical piece of evidence in the trial and expert opinion was consulted regarding the degree of the deterioration of the individual spermatozoa.

The conclusion was that the head part and the tail part of the sperm were completely severed and that it would take more than 20 days for sperm to disintegrate like that. This corroborated Govinda's statement. However, the High Court accepted a supplementary opinion that contamination by E coli bacteria and cleaning liquid in the toilet bowl could have hastened the deterioration of the sperm. This became the sole piece of decisive evidence that supported the theory of Govinda as the perpetrator.

The defence counsel conducted an experiment in which it asked five Nepalis to provide sperm samples and put them in condoms, leaving them in the toilet bowl under identical conditions. The sperm disintegrated after 20 days.

If the reasoning of the High Court which sentenced Govinda to life imprisonment, was correct it would have meant that Govinda had to have killed Watanabe on 8 March, after which he would have had to take a ride in a time machine to go back 10 days and discard his semen in the toilet. The Supreme Court supported such a ludicrous verdict.

Much of the circumstantial evidence was in favour of Govinda. For 11 days until Watanabe's body was found, he continued to live as usual in Room 401 of the Kasuya Building, down the hall from Room 101. Would a murderer do that? Govinda also had plenty of opportunities to flee the country after 8 March.

Three days after the body was found, Govinda voluntarily went to the Shibuya Police Station for questioning, fully aware of the risk of being arrested for overstaying his visa. This strongly suggests his innocence. The same can be said for Watanabe's commuter pass that was found in the yard of a private home in Sugamo, far away from the murder site, a week before the body was found.

Regarding this mystery of the commuter pass being found in a place where Govinda doesn't go, the District Court gave a fair judgment, concluding the possibilities that a perpetrator other than Govinda could be involved. However, the High Court flatly refused to take this as evidence.

Fallacy of infallibility

The Japanese police and judiciary are obsessed with the fallacy of infallibility that once indicted, the suspect has to be convicted no matter what. The Supreme Court is no longer a place where the truth is patiently pursued and justice is fairly secured. It has turned into a place where the self-protection of the justice system and miscarriage of justice are hastily secured.

I went to see the former Chief Judge Toshio Takagi without any appointment. He was the one who overturned the District Court acquittal and sentenced Govinda to life in prison in 2000. Takagi retired from the Tokyo High Court in November 2001 and later became a professor at the Law Department of Teikyo University, lecturing on Criminal Law. I waited for him in front of his research office on the Hachioji campus of the university. When I greeted him as he came back from the classroom, he looked surprised for a moment, but quickly regained his composure.

I asked him how he felt about the Supreme Court rejecting Govinda's appeal. He answered, "The ruling is totally reasonable because the District Court ruling was wrong. Now that the decision is made, it means that the Supreme Court approved of my guilty judgment. This man strangled and killed a woman. There is nothing more to say, excuse me." And he shut the door.

Out of the total of six judges that took part in the consultation, there is one who was first for rejecting Govinda's re-detention and then retracted the decision. He is Yasuhiro Muraki. In May 2001, exactly a year after Govinda's re-arrest, Muraki was himself detained by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department on charges of child prostitution, paying 20,000 yen to a 14-year-old girl. Muraki was later convicted on a violation of the Anti-Child Prostitution and Anti-Child Pornography Law. He was given a two-year sentence with a suspended sentence of five years. He was dismissed from the position of judge in an impeachment hearing, the first in 20 years.

A paedophile judge was among those who passed the verdict in Govinda's trial. This fact alone considerably damages the credibility of the judiciary. But the Supreme Court, the last-resort guardian of the law, took the lead in ratifying an act that can be described as a crime committed by the judiciary.

I went to see Muraki in Yokohama, where he lives in a newly built, high-end condominium near a train station along the Toyoko line. The entrance hall is equipped with fully automatic security locks. The elaborate security precautions, along with the inorganic exterior of the building, reminded me of the Tokyo Detention House which used to hold Govinda in custody.

Muraki himself answered the intercom. "I can't talk," he said and hung up. I could hear the sound of children's laughter in the background. Muraki had twin daughters. By a cruel twist of fate, Govinda also has two adorable daughters. The younger daughter, Elisa, is turning 10 and was born just after Govinda came to Japan. He has never seen her.

The last visit  On 4 November 2003, I went to see Govinda at the Tokyo Detention House. Wearing a white zip-up jacket, Govinda appeared in the interview cell. He looked unexpectedly well, his face had colour, but his hair which was full at the time of his arrest had now receded.

On 4 November 2003, I went to see Govinda at the Tokyo Detention House. Wearing a white zip-up jacket, Govinda appeared in the interview cell. He looked unexpectedly well, his face had colour, but his hair which was full at the time of his arrest had now receded.

"I didn't do it. I'm innocent and in jail, is it because I am from a poor country like Nepal? Mr Sano, please help me," Govinda said.

Now that Govinda has been transferred to a maximum security prison, only family members are allowed to visit and only once a month. But Govinda's family lives in Nepal. Who is going to visit him?  In an effort to save Govinda, his defense counsel wasted no time in getting ready for filing a request for a retrial. However, judging from the precedence, chances are slim. Govinda's cries of innocence will likely be muffled in prison until the day of his parole, which can take up to 20 years. By that time he will be 60 years old. Govinda will have grandchildren without having seen his daughter's husbands. His Nepali mother and father will have passed away, deeply cursing Japan, a country which framed their son for a crime he did not commit.

In an effort to save Govinda, his defense counsel wasted no time in getting ready for filing a request for a retrial. However, judging from the precedence, chances are slim. Govinda's cries of innocence will likely be muffled in prison until the day of his parole, which can take up to 20 years. By that time he will be 60 years old. Govinda will have grandchildren without having seen his daughter's husbands. His Nepali mother and father will have passed away, deeply cursing Japan, a country which framed their son for a crime he did not commit.

DOUBLE LIFE: Yasuko Watanabe (RIGHT) walked the streets of Shibuya looking for customers from the immigrant community. The apartment where her body was found on 19 March, 1997.

Govinda s story

Govinda s story The conviction, imprisonment and the rejection of an appeal of a Nepali prisoner accused of the murder of a Japanese woman has raised serious questions about Japan's justice system.

Govinda Mainali was accused of raping and killing Yasuko Watanabe, a manager at the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) who lead a double life and worked as a prostitute after working hours. On 19 March 1997, Watanabe's decomposing body was found in an empty room in the same building where Mainali and other Nepalis lived in Tokyo's Shibuya district.

She had been strangled 10 days previously. When the police came, most Nepalis fled because they thought it was an immigration raid against illegals. But Govinda turned himself in and said he didn't do it. Govinda's mistake was that he initially denied having known the woman and later admitted that he had paid for sex with Watanabe three times. The latest was ten days before the murder.

The police built up a case against Govinda, saying he had killed her for the 40,000 yen which other customers said they had paid her that evening. DNA analysis of the condom found in the room matched Govinda's and one Nepali said Govinda had paid back a loan to him at the time of the killing.

The case came to trial in 2000, and the Tokyo District Court acquitted Govinda. He was getting ready to head back to Nepal when the Tokyo District Prosecutor's office filed an appeal at the High Court and Govinda was locked up again. On 22 December 2000, the court sentenced Govinda to life imprisonment.  Japanese legal activists have taken up the case and even set up a Justice for Govinda Innocence Advocacy Group. One of them is Mikiki Kyakuno who is convinced the Nepali is innocent and says the Japanese justice system has a "deep-rooted racial xenophobia".

Japanese legal activists have taken up the case and even set up a Justice for Govinda Innocence Advocacy Group. One of them is Mikiki Kyakuno who is convinced the Nepali is innocent and says the Japanese justice system has a "deep-rooted racial xenophobia".

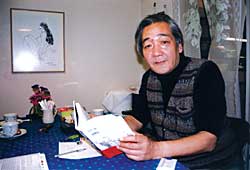

Another Japanese who has taken up Govinda's case is writer Shinichi Sano, who wrote the best-selling book, Office Lady Murder Case. Sano visited Govinda in jail many times and even came to Nepal to meet his friends and family. "I never believed Govinda was guilty," Sano said in an interview with Nepali Times in 2001 in Tokyo (see: 'Govinda', #39). "Govinda was just a fall guy from a poor country that didn't dare to make a fuss to take all the blame." After Govinda's appeal to the Supreme Court was turned down in October, Sano wrote this passionate defence of Govinda's innocence.