War is hard to capture. The heart of war is a schizophrenic place where extremes of love and hate, heaven and hell, touch and ignite each other.

Few photographers can capture this. But when they do the image is never forgotten and sometimes even change the course of history. A little Vietnamese girl, naked, fleeing a napalm attack, the soldier in the Spanish civil war caught at the moment of his death, Saddam's teetering statue or prisoners being tortured at Abu Gharib, these images lie buried in our minds and hearts and have become part of humanity's common consciousness.

When Nepal's conflict began in 1996, it was one without images. There were daily reports of increasing body counts but no photos. We did not know what a baltin bomb looked like. Today, with digital photography, Nepali photojournalists have amassed a lot of visuals. My own collection is bulging with photos cut out of newspapers.

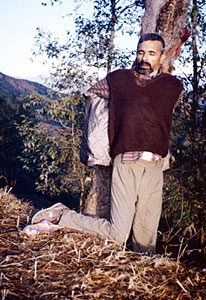

A picture of Baburam Bhattarai, Hisila Yami, Ram Bahadur Thapa and Pushpa Kamal Dahal beaming as they watch something 'in an undisclosed location'. I look carefully at their faces: they look so content and united. So well fed. I draw my conclusions but it doesn't tell me much about what war feels like out there.

A destroyed health post in Banke. 'The locals are now deprived of basic medical treatment,' reads the caption. I imagine children dying of diarrhoeal dehydration, anemic women without iron tablets, untreated broken bones, infecting wounds, women dying at childbirth.

More images of destroyed buildings. Government offices in Charikot, schools in Gurkha, police posts and airports all over the country. I imagine a country bombed back into history, decades of development undone.

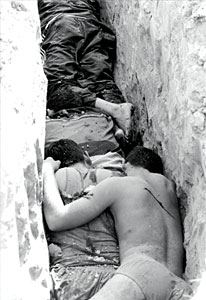

Lots of pictures of dead bodies. A pile of policemen bodies in Bhakunde Besi. The first layer of corpses is vertical. The faces seem identical: a wave of thick black hair, well-defined eyebrows, long noses. The second layer consists of policemen with feet pointing at the camera, almost touching the face of a fellow-policeman below. A policeman wearing blood stained gloves pulls the legs of a body towards him. Around the pile are remains of what look like a basket, spades and rocks. Two policemen sit on a low wall, one of them has crossed his legs in a comfortable position.

Pictures of 'Maoist' dead in Khara, scattered across the terrain. Lovely faces, perfectly shaped feet, strong legs-these boys could have been lovers, surgeons, sportsmen, mountaineers.

Then there is one particular picture I can't look at for long. The one of Lamjung teacher Muktinath, Adhikari, crucified against a tree. I know exactly what the Maoists did to this man but don't want to remember. It's enough to watch, for a minute, the image of a dead man on his knees, handcuffed from the back, shirt spilling out of his trousers. It's enough to watch his face, the eyes closed in intense sorrow, mouth slightly open as if still wanting to speak: "Don't do things you might later regret." Four years later, I can almost hear Muktinath say: "Don't hurt, don't destroy, don't take life."

Tucked away at the bottom of my folder are pictures of mourning relatives. I can almost touch the war here. An army personel is killed in Rolpa. In Kathmandu relatives cry after hearing the news. The wife is lying on the floor, a man (her brother-in-law?) holds her face with both hands. The man himself is visibly distressed, crying and speaking at the same time. A woman (his sister?) presses the palm of her hand against his face, in comfort. Another man wipes tears from his cheeks and holds the first man by his shoulder. There are many hands reaching out in grief and chaos: a tableau vivant depicting the human ability to create and destroy.

A picture that really brings the war home to me is one that hits me like a nail, splits open my head and fills me with revulsion, sadness, compassion. It is Suresh Sainju's picture of three children after the death of their father, a policeman.

The eldest son sits in the middle, sisters on his left and right cling to him. The sister on the left tilts her head back a little, her mouth is open. The sister on the right embraces the brother with her left hand and cries into his shoulder. But it is the brother's face that touches me the most. His eyes upon his sisters trying to take it all in his face frozen with thoughts that can't be spoken. The responsibility on those young shoulders, the only male in the family. Rituals, cremations, documents, his sisters' education, money.

Can anyone look at this photo and continue the destruction?

KILLING PEOPLE IS WRONG

Muktinath Adhikari's body lies crumpled near his village in Lamjung after he was tortured and killed by Maoists in 2002.

Debi Sunuwar, the mother of 15-year-old Maina Sunuwar after learning that her daughter was dead eight months after being disappeared from her village in Sindhupalchok by the army in Feburary 2004.

An army honour guard salutes fallen comrades at Pashupati's cremation site in February 2002 after the battle for Mangalsen.

Kailash Gupta who sells corn on the roadside in Nepalganj is only six, his mother died in a Maoist landmine blast in which his sister Tara was injured.

The son of a civilian killed by Maoists in Bhaktapur comforts his sisters.

Parbati Duwadi of Thanti in Lamjung lies in a pool of blood after being killed in a crossfire while her brother-in-law holds her infant son.

Students from Krishna Secondary School in Lalitpur on being released in July 2004 by Maoists after three days of forced-marches and indoctrination.

Syani and Kumle Praja of Jogimara in Dhading who became widows at age 15 when their husbands were killed by the army in Kalikot in 2002.

Bodies of policemen who were killed in the trenches of Satbaria after a Maoist raid in April 2002.

Maoist leaders Prakash Dahal (Prachanda's son) Baburam Bhattarai, Hisila Yami, Ram Bahadur Thapa and Prachanda at an undisclosed location.

Sona

Just before noon on 9 May 2004 a crowded Kathmandu-bound bus from Jiri stopped at Mainapokhari. Suddenly, a fierce firefight broke out between soldiers and the Maoists in the slopes above. The bus was caught in the crossfire and was riddled with bullets. It was all over in 15 minutes, combatants on both sides suffered casualties. Six passengers in the bus were also killed.

Just before noon on 9 May 2004 a crowded Kathmandu-bound bus from Jiri stopped at Mainapokhari. Suddenly, a fierce firefight broke out between soldiers and the Maoists in the slopes above. The bus was caught in the crossfire and was riddled with bullets. It was all over in 15 minutes, combatants on both sides suffered casualties. Six passengers in the bus were also killed.

In Kathmandu, the media flashed this famous picture of Krishna Maya holding her 20-day-old grand-daughter, Sona, in her lap outside Chhauni Hospital where the little girl's mother, Nani Maya, was being treated after being critically wounded. She survived, but her father, Shobendra Kafle, died on the bus.

Gopal Chitrakar's photograph shocked the nation. No reader who saw this image in Kathmandu Post and Kantipur last year could have remained dry eyed. Among them was singer and composer Amrit Gurung of the band, Nepathya. "For me, that tiny girl symbolised the Nepali nation itself, orphaned, terrorised but with a future ahead of her," Amrit says, recalling how he travelled to Mainapokhari a week after the incident.

The asphalt still had blood stains, the air was still heavy with death and loss. Amrit talked to villagers and eye witnesses. On the drive back, he composed a haunting song in the folk Nepali gaine-inspired rock ballad. The number is the lead song in the Nepathya album Ghatana which was launched without fanfare on Thursday. The band will soon be going to Mainapokhari to perform at the spot where the incident occurred.