Trekking is hard work, and that is perhaps part of its charm. The physical effort, the discomfort, the delicious muscle aches are a great way to get away from the comforts and amenities of the modern world. For a while, anyway.

Trekking is hard work, and that is perhaps part of its charm. The physical effort, the discomfort, the delicious muscle aches are a great way to get away from the comforts and amenities of the modern world. For a while, anyway. But there is always the problem of the night stop. However gruelling the day, the climb up and down a 5,000 m Himalayan pass in eight hours, it is always nice to come to a cosy and warm inn on the other side. There are plenty of cosy trekking lodges in Nepal, but very few that are warm enough.

Keeping rooms and dining areas of trekking lodges warm at high altitude has always been a challenge in a country where central heating is non-existent and houses lack insulation. In most Nepali homes, the kitchen is about the only place that is warm, and we have a notoriously slack attitude towards heat loss. The result: freezing rooms where you breath comes out in clouds of condensation as you try to snuggle into your sleeping bag.

There was a time when the Himali Inn in Mustang's Jharkot village was the only trekking lodge on the trail up to Muktinath. It was a labour of love for the Thakuri family that owned it, and an itinerant American named David Doverner whose concepts of energy efficiency and appropriate technology were way ahead of their time.

There was a time when the Himali Inn in Mustang's Jharkot village was the only trekking lodge on the trail up to Muktinath. It was a labour of love for the Thakuri family that owned it, and an itinerant American named David Doverner whose concepts of energy efficiency and appropriate technology were way ahead of their time. Jharkot is north of the Himalaya in the rain-shadow. Firewood is scarce, the winds are deadly and the winters here at 3,200 m are Siberian. So, how do you heat a trekking lodge?

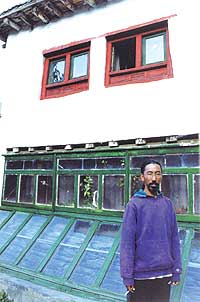

Doverner and his Mustangi family designed the Himali Inn to cleverly use a three-sided design to trap solar energy. As soon as the suns pops out from behind Thorung Peak to the east, it strikes one side of the house, during the mid-morning to noon period it bakes the middle portion, and again in the afternoon the slanting rays strike the other side.

The heat traps are set at the base of the building, jutting out into the porch like a greenhouse. The only difference is there are no plants underneath the glass, but piles of stones all painted matted black. The greenhouse effect heats the stones throughout the day, and warms the entire house through convection.

The heat traps are set at the base of the building, jutting out into the porch like a greenhouse. The only difference is there are no plants underneath the glass, but piles of stones all painted matted black. The greenhouse effect heats the stones throughout the day, and warms the entire house through convection. During a recent autumn night, the temperature outside was minus 2 Celsius, while the rooms at the Himali Inn remained at 18 degrees.

"The beauty of it is that it costs almost nothing, and it is virtually maintenance free," says Norbu Thakuri, whose family owns the inn. "The only maintenance we have done in the past 25 years is to replace glass panes broken by a drunk and when a block of ice fell from the roof."

Once a year, the inn opens up the glass panes, gives the stones a new coat of black made from the inside of dry cells, and dusts the air passages. That is all it takes.

Even with the Himali Inn prototype, there is room for improvement. For instance, metal frames encasing the glass would be more permanent and air-tight than wood, double-glazing would improve insulation, stones can be selected for better heat retention, and arrayed for increased surface area. Then, of course, there is the need to make the windows and doors in the house more air-tight and to reduce heat loss through the roof and walls. All this would make the system cost slightly more, but would make it even more efficient.

What is surprising is not how well passive solar space heating works, but why it hasn't caught on along the trekking trails in the rest of Nepal. Given Nepal's success story in designing and marketing solar water heaters, it would have been a logical extension to sell home space heaters. Maybe some day it will happen, and when it does, it will help save millions in kerosene and firewood.

What is surprising is not how well passive solar space heating works, but why it hasn't caught on along the trekking trails in the rest of Nepal. Given Nepal's success story in designing and marketing solar water heaters, it would have been a logical extension to sell home space heaters. Maybe some day it will happen, and when it does, it will help save millions in kerosene and firewood. Says Norbu's elder brother, Rajendra: "It's a great idea, but the challenge is to get the younger generation fired up about the concept, especially since it makes so much business sense, while at the same time being environment friendly."