At 18, Damodar Narayan Suwal was the Nepali liaison officer with a British expedition to Api-Saipal Himal in 1955. Little did he know that the expedition was on a spying mission on behalf of Indian intelligence to find out what the Chinese were up to on the plateau. Nepali Times tracked down Damodar in Kathmandu and heard his side of the story in Sydney Wignall's new book, Spy on the Roof of the World.

At 18, Damodar Narayan Suwal was the Nepali liaison officer with a British expedition to Api-Saipal Himal in 1955. Little did he know that the expedition was on a spying mission on behalf of Indian intelligence to find out what the Chinese were up to on the plateau. Nepali Times tracked down Damodar in Kathmandu and heard his side of the story in Sydney Wignall's new book, Spy on the Roof of the World. It had been six years since India became independent. Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru saw a hegemonic west as more of a threat to new nations emerging from colonialism. He was trying to forge an alliance of "non-aligned" nations and was to rope in other like-minded Third world leaders like Ghana's Nkrumah and Indonesia's Sukarno. For this, he felt China and India should stick together and his slogan was \'Hindi-Chini-Bhai-Bhai".

Nehru's closest adviser on China was his foreign minister, Krishna Menon. But the Indian military was deeply suspicious about Menon who it thought was a closet-communist, and who refused to give a green light for intelligence-gathering on Chinese plans in Tibet for fear that it would offend Mao Zedong.

An intelligence operative at the Indian High Commission in London who went by the name "Singh" seemed to know about Wignall's permission from the Nepal government to climb Nalkankar (7,100m) and approached him to see if he could slip into Tibet and climb Gurla Mandhata (7728m). From that vantage point, it would have been easy to pick up information on any Chinese military activity.

From the account in his book, Spy on the Roof of the World, Wignall appears to have willingly agreed to be a spy. But he didn't tell the rest of his team. As it turned out, the Chinese were right when they arrested the three expedition members on the slopes of Nalkankar for being on a spying mission. Wignall managed to gather information even during his detention about a strategic highway the Chinese were building towards western Tibet, and an estimate of the garrison strength at Taklakot. But this information didn't do the Indians much good, since Nehru and Menon ignored it and were caught unawares when the Sino-Indian war erupted in 1962 during which large numbers of Indian soldiers, including Nepali Gorkhas, were killed in the icy mountains of Arunachal Pradesh and Askai Chin.

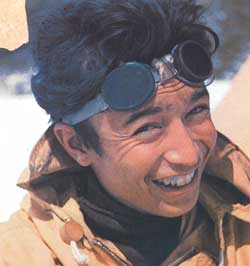

From the account in his book, Spy on the Roof of the World, Wignall appears to have willingly agreed to be a spy. But he didn't tell the rest of his team. As it turned out, the Chinese were right when they arrested the three expedition members on the slopes of Nalkankar for being on a spying mission. Wignall managed to gather information even during his detention about a strategic highway the Chinese were building towards western Tibet, and an estimate of the garrison strength at Taklakot. But this information didn't do the Indians much good, since Nehru and Menon ignored it and were caught unawares when the Sino-Indian war erupted in 1962 during which large numbers of Indian soldiers, including Nepali Gorkhas, were killed in the icy mountains of Arunachal Pradesh and Askai Chin. It all happened nearly 50 years ago, but for Damodar Suwal the memories of those six months of dare-devil mountaineering in the remote far-western corner of Nepal, and being locked up in a dingy jail in Tibet, are as fresh as ever. Damodar was 18 years old in 1953, he had just returned to Nepal after finishing high school in Banaras. He was weak in maths, and was waiting for admission at Tri Chandra College when he heard that the Foreign Ministry was looking for liaison officers to accompany mountaineering expeditions. "I applied and got in, there wasn't much competition in those days," Damodar recalls.

He was first assigned to an unsuccessful Kenyan expedition on Himalchuli. Then he was sent to Tanakpur to meet another British expedition which had got permission to climb the virgin peak of Nalkankar on the Nepal-Tibet border. He met the expedition leader, Wignall, who was impressed with this young and energetic Nepali.

They travelled to Pithoragarh along a highway on the Indian side, and crossed over into Nepal at Jhulaghat in Baitadi, and through Bajhang to the base of the Saipal range-a 19-day trek through monsoon downpours. The snow was thick, and the expedition couldn't move forward or back. Food was running out.

Sydney Wignall and John Harrop explored the surrounding mountains and wanted to make an attempt on Nalkankar. "There were no border pillars along this area, and we had sent porters down to a village for food. It turned out we were already inside Tibet and the porters came back with Chinese Peoples' Liberation Army guards who arrested us," Damodar remembers.

What followed was a harrowing 45 days in a "jail" which was a converted Tibetan house with four rooms. After a week, the commissars arrived for the interrogation. The sessions lasted up to two hours each and the three were interrogated separately.

What followed was a harrowing 45 days in a "jail" which was a converted Tibetan house with four rooms. After a week, the commissars arrived for the interrogation. The sessions lasted up to two hours each and the three were interrogated separately. "They asked me what I was doing there, how come I was with these foreigners, and my answer was that I was a Nepali liaison officer assigned to this expedition which was climbing a mountain in Nepal," Damodar told us. He told the Chinese that since they couldn't climb Api, Saipal or Nampa, the team had decided to climb Nalkankar, and accidentally strayed into China. The interrogators were convinced the British were spies, but according to Damodar did not treat them too badly. This is contrary to Wignall's account in the book where he says most of the Chinese guards (except one) were cruel to the prisoners.

Damodar says they used to get a pot of water in the mornings, and they ate whatever the Chinese guards ate. The guards took their jobs seriously and always pointed their assault rifles at them, warning them if they looked around.

"Suddenly, one day they released us. Gave us three porters, food for five days-dried meat, sugar and tsampa. They told us to go back into Nepal the way we had come," says Damodar. The return was a perilous crossing of the 5,000 m Urai Lekh pass in winter. By the time they made their way down the Seti gorge to Bajhang, they had run out of money and food. Wignall sold his pistol to the Raja of Bajhang Om Jung for 150 Indian rupees. This is the same Om Jung who was killed in an anti-government revolt in the early sixties.

"I went straight to our embassy in Delhi and met the ambassador, Jharendra Narayan Singh. Embassy staff bought me some new clothes, and made me sign papers not to tell anyone about what had happened since it may jeopardise Nepal-China relations. Then they put me on a plane to Kathmandu the next day," says Damodar.

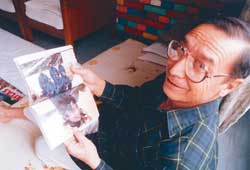

Damodar never climbed any mountains after that, and he worked for 25 years for USAID in Kathmandu as a programme specialist. Only after the book came out this year did Damodar find out that he was a member of a spy expedition. "The climbers never talked to me about it," recalls Damodar. "After reading what it was all about, all I can say is that I am slightly embarrassed about the whole thing."