How many forced closures are necessary to prove the utter futility of all bandhs? In any case, what difference does it make stopping vehicles from plying the national highways, when the normal life of the entire population-save the Maoists and the security forces-is, for all intents and purposes, shut down anyway?

How many forced closures are necessary to prove the utter futility of all bandhs? In any case, what difference does it make stopping vehicles from plying the national highways, when the normal life of the entire population-save the Maoists and the security forces-is, for all intents and purposes, shut down anyway? Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba is no less tactless than the Maobadi leadership. The declaration "Wanted, dead or alive", with a price on the head of the fugitives, is a sign of desperation, not confidence. Perhaps taking his cue from Sheriff Bush in the unfolding saga against terror in the Afghan desert, Prime Minister Deuba has committed the cardinal sin of democratic politics-adopting patently unconstitutional means to achieve what could be justifiable ends.

There is little doubt that Comrade Prachanda and his cohorts can be charged with breaking almost every law of this land, but that can't possibly justify the government donning the judge's mantle. Even if the government were to be prosecutor, judge and executioner all rolled into one, capital punishment is not a provision of the constitution that Deuba is oath-bound to protect. There could be a somewhat more charitable interpretation, that it is all a part of the psy-war against the insurgents. If that is the case, perhaps an announcement that the bounty could be claimed from Royal Nepal Embassies abroad might be an added inducement.

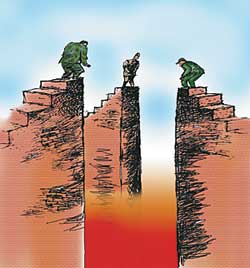

Either way, this running around in circles is ruining Nepali society and the country. Sometimes it is the Maobadi doing the chasing, at other times the government forces, spreading their security net. But the territory remains the same, no matter who is on the run-it is us ordinary Nepalis being run over. Most of us in Kathmandu would probably respond in the negative if asked whether there is a way out of this quagmire. And then we'd quietly go on doing whatever we are doing at that moment, safe in the belief that the danger will disappear all by itself. Fatalism is a facile explanation for this collective sense of worthlessness, but it will have to do for the lack of a more appropriate term.

But there are some Nepalis abroad who think otherwise. Writing in Nepal, Rabindra Mishra of the BBC Nepali Service outlines four options for Nepali society:

(1) Apply pressure on our leadership to mend its ways;

(2) Submit to the direct rule of the king;

(3) Continue with the current apathy and lack of commitment; or

(4) Abjectly surrender to the demonic forces of Prachanda.

Like a good democrat, Mishra insists that his preference would be the first one. Sure, distance gives perspective, but it also makes it harder to notice details. Creating public pressure in the fond hope that the present political leadership of the country will mend its ways looks increasingly like chasing a mirage. The possibility of direct rule by the king under present circumstances-so soon after 1 June and the incendiary rumours that spread in its aftermath-is fraught with grave dangers. Allowing the current apathy to continue is like quietly awaiting your turn at the gallows. Sooner or later, every one who does not oppose tyranny is sure to end up there.

Mishra's last option is no option either. It implies the end of common Nepalis' quest for an independent identity, democratic rule and social justice. None of these suggestions are choices we can make of our own accord. They are the eventualities that we have to prepare for if the "fight-to-the-finish" between the security forces and the insurgents does not end in a workable compromise.

Sadly, the possibility of a compromise has been further reduced after the American promise of $20 million worth of military hardware on the one hand, and a clear division in the ranks of Maoists on the other. Even if the Nepal Communist Party (Maoist) was to sit down for talks with the government, it's far from clear whether the more militant Nepal Maoist Centre would also agree to lay down arms and play fair. It's not a comfortable thought, but the fact is, there is simply no easy way out of the present impasse. Our political leaders of all hues and the Maobadi both know that. Nepal is trapped in a Mahabharata-type no-win internecine war.

There might, however, be one political experiment left to be tried-the formation of a high-level Royal Commission by the king upon the recommendation of the council of ministers, with nominees from political parties as well as "intellectuals" sympathetic to the Maoist cause as members. May be such a high-level political instrument will be able to convince the insurgents to lay down arms and settle for something a

little less than what they desire, but a lot more acceptable than what is presently available.