Imagine a regular Kollywood film attempting to portray something like a generation gap, or changing values in a family with three generations. What do you see? A dotty grandmother, deeply conservative and slightly ridiculous parents, and children who simply want to drink, smoke, burn down the dance floor and wear short, shiny clothes.

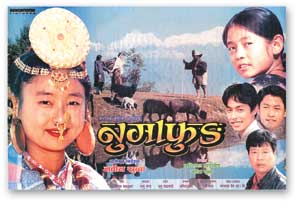

Imagine a regular Kollywood film attempting to portray something like a generation gap, or changing values in a family with three generations. What do you see? A dotty grandmother, deeply conservative and slightly ridiculous parents, and children who simply want to drink, smoke, burn down the dance floor and wear short, shiny clothes. Now imagine a Nepali film that eschews all of that and meditates on change through something more basic-language. In Nabin Subba's Numafung, the oldest family members speak only Limbu, the second speak Limbu and Nepali, and the youngest speak only Nepali.

It's a sign that Nepali film directors are finally starting to mature, separating themselves from Bollywood's trend of gratuitous sex, violence and slapstick, producing truly original works that depict the real Nepal. After the 2000 success of Tsering Rhitar Sherpa's Mukundo, Numafung is another film that makes you want to sit up and rub your eyes in disbelief.

Numafung is the story of how a Limbu girl finally decides to take charge of her life after learning from the suffering and pain that her earlier misdirection gave rise to. Numafung, which in Limbu means \'beautiful flower', is based on the story Kaarbar ki Gharbar by Kaziman Kandangwa.

First-timer Anupama Subba essays with style, passion and just the right amount of restraint the role of Numafung, a young Limbu woman in a village in contemporary east Nepal. Through a series of events in which Numa has a gradually diminishing say-arranged marriage, widowhood, miscarriage and then forced remarriage-the film's tacit message fills out. It is so easy for women like Numa to be the first to be disempowered when caught in the tyranny of a society conflicted about the future.

Numa's second husband Girihang, played by veteran stage and screen actor Prem Subba, is a classic-the spoilt son of a wealthy family, an alcoholic who has no qualms about domestic violence. The many scenes in which Girihang publicly humiliates Numa are all the more chilling for the fact that they fall neatly within the realm of real possibility. Girihang's alcoholism and the physical violence drive Numa back to her parents house. It's a scenario common in the everyday life of communities, where alcohol has traditionally been a part-the old ways of brewing, drinking and regulating consumption have fallen apart in the face of modernity and its new occupations, focus on cash, and divisions of time.

The united, empathetic relationships between the female characters in the film provide a nice counterpoint to the conflict between tradition and change plays out in the world of men. Both her mother-in-law and her grandmother Fungloti, played by 82-year-old Rammaya Tumrock, do more than passively bear witness to Numa's life slowly going out of her hands. They show, by standing up for her, that they don't buy the argument that such rows between husband and wife are "trifling", as Girihang tries to convince her they are. And so Numa, realising that someone at least is on her side, eventually musters up the courage to take control of her life.

All of this comes to the viewer through the eyes of Numa's younger sister, Lojina, whose attachment and loyalty to her sister are apparent right from the first frame of the film, where she is picking a white chrysanthemum to put in Numa's hair. Young Niwahangma Limboo, in reality a pigtailed Gangtok schoolgirl, slips easily into the role of a young village girl whose prophetic nightmares offer an insight into the innocent mind. As the story progresses from one chapter to another, the titles that appear on the screen are those from Lojina's point of view, as is obvious when a title comes on describing Girihang as Mote Bhena-fat

All of this comes to the viewer through the eyes of Numa's younger sister, Lojina, whose attachment and loyalty to her sister are apparent right from the first frame of the film, where she is picking a white chrysanthemum to put in Numa's hair. Young Niwahangma Limboo, in reality a pigtailed Gangtok schoolgirl, slips easily into the role of a young village girl whose prophetic nightmares offer an insight into the innocent mind. As the story progresses from one chapter to another, the titles that appear on the screen are those from Lojina's point of view, as is obvious when a title comes on describing Girihang as Mote Bhena-fat brother-in-law.

The story is compelling, as is the manner in which the characters are developed, and the backdrop of Nagi village in Panchthar district is spectacular, with magnificent views of the Kumbakarna or Mt Jannu. All of this more than makes up for the choppy editing. Director Subba agrees and says, "Technically, we haven't been able to achieve good quality, but I believe in learning by doing. I'm sure in due course we will be able to produce films of excellent quality."

Subba already has three feature films to his credit. His first, Tarewa, was a telefilm in Limbu language, and his second, Khangri, which was about a Sherpa community, did the international circuit, even winning the Jury Award at the 1997 Graz Film Festival. Numafung isn't just another commercial film being arty, it is as much a well-researched ethnographic document of the changing ways and lives of rural Limbu people. It's obvious in the way each member of the family sits in their precise, designated spot during meals, in the scenes of grandmothers weaving on traditional handlooms, in the easy, unfettered interaction of young men and women in village markets.

But Subba is careful not to be prescriptive, or pretend to be authoritative. "My job as a director is not to distinguish between culture and religion, right and wrong. We have done much research for the film and I was only showing what is prevalent in the community at the moment." And so, though some viewers say Subba's characters should have been more "authentic", he insists that central to the change he is concerned with in Numafung, is the notion that cultures cannot but mix, and that it is up to individuals to decide how they want to deal with it. The problem, says Subba with a smile, will be clear when this film goes to the masses. "How do we manipulate society's psychology into accepting Numafung? That's a similar challenge."