Nepal should not be turned into another Afghanistan." It has become irresistible for politicians of every hue to proclaim those words from pulpits across the land.

Nepal should not be turned into another Afghanistan." It has become irresistible for politicians of every hue to proclaim those words from pulpits across the land.

They mouth the words, but it is doubtful if they have studied the history of how multi-ethnic Afghanistan entered such a hopeless vortex of violence and destruction. A lot had to do with failed governance within Afghanistan, its fickle alliances and frequent back-stabbing. Sound familiar?

Lest we forget, these intractable internal rivalries were largely stoked and fomented by Afghanistan's neighbours for their own short-term advantage. The Afghans were proxies of regional powers who in turn were the proxies of the superpowers. Bin Laden used to be an American proxy, Mullah Omar was a Pakistani proxy. Ahmed Shah Masood was a Russian proxy.

As Michael Ignatieff warns in this issue (p 13) proxy wars are easy to fight, but the danger is that proxies run away with their own agenda, and then mess up the agenda of those who think they are controlling the proxies. History shows us that in geo-politics, short-term advantage is almost always a long-term disadvantage.

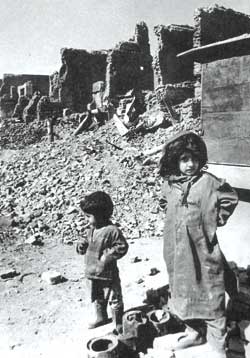

It was, and is, Afghanistan's great misfortune that it is so strategic, straddling the crossroads between civilisations. Ever since the Moghuls rode over the Khyber Pass, all through the Russo-British Great Game, the disastrous Soviet occupation, and finally to the present day when the country became a haven for extremists from all over the Islamic world, no one has ever left Afghanistan alone. This hostile land peopled by fierce tribes became the graveyard for many invaders who had to slink away with tails between their legs.

This month, the Taleban political structure finally collapsed under the weight of American firepower. Something happened in Afghanistan in the first week of November 2001 that probably marked a turning point in the history of military campaigns. As a response to suicidal terror, we saw the application of a new doctrine of high-tech distance warfare a la Tom Clancy. Twelve years after the Gulf War, we have seen the awesome advances in military hardware and technology which now obviate the need for full frontal invasions, supposedly minimise "collateral" and "friendly" casualties, and allows the conduct of virtual remote control warfare.

So far so good. But however euphoric the talking heads on CNN may sound, America's war on terror is not over. In fact, it may just be beginning. The Taleban could just dig in and keep fighting a guerrilla war, Afghanistan may be partitioned between north and south. But how is this new high-tech war going to fare in the next phase when it can't be fought by remote control anymore?

And the most frightening part: al-Qaeda is still loose and it is more enraged than ever before. Is America more secure than it was before the Afghan bombing began. They'd be fooling themselves if they thought so.

Despite all this, if there was a worthy outcome from the deaths of innocents in New York and the misery of millions in Afghanistan, then it must be that one of the most repressive, intolerant and obscurantist regimes on earth has been unseated. Also, the world's only superpower seems to have realised that multilateralism is the way to go and there may be some use for the United Nations after all. (Now maybe Washington will finally pay up its UN dues.)

Yet, in our own region, India and Pakistan continue to see the unfolding drama in the Hindu Kush from their own narrow prisms. For them, it's still about Kashmir. Numerous pundits on satellite talk shows continue to rant about how India or Pakistan can earn brownie points from the misfortune of the other. There are few with the clarity of thought of Indian analyst K Subrahmanyam, who argue that after the Taliban is defeated, everyone's (the US's, India's, Russia's, Pakistan's) common goal should be a moderate Pakistan.  So what lessons for us? Nepali history and geography have parallels with Afghanistan. We are also multi-ethnic, we are strategically located, we also have a history of domestic intrigue and outside meddling, and we are as fiercely independent as the Afghans. Our strength can come from visionary leadership that can show integrity and commitment to economic progress that makes us more self-reliant and in control of our own destiny.

So what lessons for us? Nepali history and geography have parallels with Afghanistan. We are also multi-ethnic, we are strategically located, we also have a history of domestic intrigue and outside meddling, and we are as fiercely independent as the Afghans. Our strength can come from visionary leadership that can show integrity and commitment to economic progress that makes us more self-reliant and in control of our own destiny.

Our squabbling politicians may want to learn the lessons of Afghanistan and resolve not be proxies for anyone for short-term gain. Proxies are expendable, and they are abandoned first by their mentors.

The forthcoming and much-delayed SAARC Summit in Kathmandu in January will be largely symbolic photo-op. Anything can happen during December. Still, it could be an opportunity to forge a "Kathmandu alliance" to declare Nepal and the smaller South Asians a proxy-free zone.