According to the World Health Organisation, anaemia should be considered a "significant public health problem" if one-fifth of the population suffers from it. The rate of iron deficiency in blood among Nepali women and children is four times higher than that.

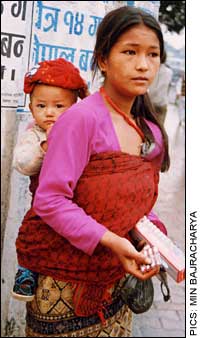

According to the World Health Organisation, anaemia should be considered a "significant public health problem" if one-fifth of the population suffers from it. The rate of iron deficiency in blood among Nepali women and children is four times higher than that. Two out of three Nepali women are anaemic. This number goes up among pregnant women to three in four. And anaemia in Nepal is no longer only about women. An alarming 90 percent of infants under the age of one are anaemic, according to the Nepal Micronutrient Status Survey 1998. Kyoko Okamura of UNICEF Kathmandu's Nutrition Section is emphatic about the consequences: "We are producing a whole generation of Nepalis who are less competent mentally." Iron deficiency anaemia can cause adverse health consequences including impaired growth, slowed learning and cognitive development, and decreased physical activity in children below 12 months of age.

Simply put, most anaemia results from an iron deficiency. Iron, a micronutrient required in small, but critical, quantities, is essential for the production of haemoglobin, which form the all-important red blood cells. Since haemoglobin is essential for the delivery of oxygen from the lungs to body tissues, and the synthesis of iron enzymes that are required for oxygen utilisation and energy metabolism, if you don't have enough red blood cells, you breathe less efficiently, which means you're constantly short of breath and your energy levels are nowhere near what they should be.

"This is a serious public health crisis," says MR Maharjan of The Micronutrient Initiative (MI). More than most other illnesses, the economic impact Iron Deficiency Anaemia is significant, as it causes a sharp reduction in physical activity and work output in adults-between 20 and 40 percent. An MI study claims that Bangladesh and India lose 1.9 and 1.3 percent of their GDP respectively to anaemia every year. There haven't been any studies in Nepal, but public health experts and epidemiologists estimate that the figures would be just as dramatic here. As importantly, anaemia increases the risk of maternal, prenatal and perinatal mortality. Nepal has the fourth highest maternal mortality rate in the world- 539 in each 100,000 pregnant women-and UNICEF says if it can be reduced significantly, 20 percent of these deaths could be prevented.

"Our food habits are problematic-anaemia is more visible among high-caste Hindus who eat ritually prescribed vegetarian food, and less among meat-eating janajati communities like Gurungs and Newars," said Sharada Pandey, chief of Nutrition Section at the Health Ministry's Child Health Division.

Only 15 percent of the Nepali population eats enough meat-based food rich in naturally available iron. The remaining 85 percent depend on vegetarian diet for cultural and religious reasons, or because they simply can't afford meat. Women, whose iron needs are more significant anyway, suffer doubly because of their lower social and nutritional status. Not getting enough food already accounts for chronic energy deficiency in one in four women in Nepal. According to WHO standards more than 20 percent of women with chronic energy deficiency indicates a serious public health problem.

Eating right is only one part of the story. The scale of anaemia in this country is an indicator of many more problems than just food habits: it points to the low socio-economic status of women, poor, sometimes non-existent sanitation that spreads and exacerbates the prevalence of parasitic diseases, and the inadequate decentralisation of health services.

In 1999/2001, some 45 million iron tablets were procured for free distribution for across the country. Less than half, about 20 million, were given out. "The iron tablet supplies are more than sufficient, but the system to distribute them doesn't work," says Okamura of UNICEF"s Nutrition Section, which provides commodity support to the government for its universal iron tablet distribution programme for pregnant women.

The sub-health posts are the lowest level health care institutions that are allowed to distribute iron tablets, had an average of 8,000 tablets at any given time. But most of the time sub-health posts are out of reach of the people who need supplementary iron the most. It takes an average of two to three hours for most women to reach the sub-health post nearest to their homes. When so many women don't have the power to make decisions or control even their own earnings, let alone the family income, taking time out from an already packed day to even get adequate prenatal care, let alone iron tablets, is a tough proposition.

Women who manage to receive antenatal care are five times more likely to take supplementary iron, but less than half of Nepali women ever receive antenatal care from a medical professional in the first place. Complicating this, two-thirds of the health care workers at sub-health posts say they are simply too overburdened to dispense the tablets with the accompanying talk on the benefits and side effects of supplementary iron.

Women who manage to receive antenatal care are five times more likely to take supplementary iron, but less than half of Nepali women ever receive antenatal care from a medical professional in the first place. Complicating this, two-thirds of the health care workers at sub-health posts say they are simply too overburdened to dispense the tablets with the accompanying talk on the benefits and side effects of supplementary iron. It shouldn't have taken so long to realise it, but at last the Health Ministry decided that the only way to improve women's access to iron tablets was by making them available to community health workers. A pilot phase of what is called the "iron intensification programme", which allows women community health volunteers to distribute iron tablets, was launched last year with very encouraging results. In wards of Bhaktapur, Banke, Sunsari and Saptari where the program was implemented, the use of iron tablets went up to 80 percent of pregnant women. Since one female volunteer only looks at five to 10 pregnant women at any given time, distributing iron tablets isn't a huge burden. The Micronutrient Initiative, which works with the government, hopes to launch a full-fledged iron intensification programme in Jhapa, Dhanusha and Mahottari districts by the end of this year.

But distribution of iron tablets, while it has uses, is hardly a foolproof way of tackling anaemia. For one, community health workers are uncertain about when they should give out the tablets, because anaemia rarely has stark symptoms. Even trained health workers sometimes mistakenly believe that as long as women eat fruits and vegetables regularly, they don't need supplementary iron, even if they are pregnant. Women with severe anaemia account for 2.2 percent of the female population of Nepal, but among pregnant women as many as 5.7 percent of women are severely anaemic.

Pregnant women need two to three times as much iron as normal as the body's requirement increases with the increase in blood volume and the growth of foetal and placental tissue. In Nepal, the policy is that all pregnant women should get 60 mg iron per day from the start of the fourth month of pregnancy and continue through 45 days after birth. But coverage is very low and adherence to the full supplementation protocol is extremely poor.

The Nepal Demographic Health Survey 2001 shows that 77 percent of women did not take iron tablets in their last pregnancy because they just didn't know about them, or thought that their regular diet was nutritious enough. Still others who do take the tablets often discontinue them too early because they feel like they have regained their strength or because the side-effects-stomach cramps and dark stools-worry them.

Iron deficiency in mothers means severe anaemia among children. WHO reports say that one in seven Nepali women is considered to be at nutritional risk, which means a direct impact on the nutrition levels of her child, and there is a stark lack of programmes that target at correcting anaemia among the adolescent girls of childbearing age. Studies show that two-thirds of all non-pregnant women are anaemic, which means that they enter a pregnancy with already-depleted stores of iron. The Nepal Micronutrient Status Survey 1998 shows that 90 percent of Nepali babies between six and 11 months old are anaemic, about three percent of them severely so. This age group is particularly vulnerable, as breastmilk does not fulfil an infant's iron needs after six months, and the iron stores that the infant is born with start to get depleted. After that age, the complementary diet is often too low in bioavailable iron to fuel the rapid tissue growth that takes place.

Despite the shortcomings of the supplementary iron regimen, food-based intervention against iron deficiency is difficult in Nepal because most families are too poor to diversify their diet, and even those that have a varied diet don't use the best cooling methods, with less water and a shorter cooking time. It is possible to fortify some food items, and the MI hopes to begin fortification of wheat with five mincronutrients, including iron, as soon as the Finance Ministry agrees to it. The cost of fortification will be passed on to consumers, but the MI's Maharjan says that it is almost unnoticeably low-around 10 paisa per kg, even lower than the cost of iodising salt.

MI studies show that 30 percent of Nepali household consume flour-based food everyday, and that the figure goes up to 50 percent in urban areas. Monitoring the 20 large-scale flourmills that produce more than 40 metric tonnes per day would be relatively easy, but addressing the small-scale, locally-operated flourmills will be a challenge that the MI says it will be ready to take up by the end of 2002.