On Friday night, the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) took in about two dozen officials from the revenue administration. While we all wait to see how the commission follows through on this campaign, it is clear that the crackdown finally addresses the rot within.

On Friday night, the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) took in about two dozen officials from the revenue administration. While we all wait to see how the commission follows through on this campaign, it is clear that the crackdown finally addresses the rot within. It is a jungle out there, and only the strongest survive. But civilised societies are governed by values and morality that are presumed to be rational. Every society also has the types that don't bother about the law, and even less about its implementation.

We in Nepal are now at a stage where we all want to set up to a system of governance that promotes sustainable human development through a rule of law. Sound economic policies presume that decisions directly or indirectly facilitating the creation of wealth and its equitable distribution will be fostered. Good administrative governance is a system of policy implementation carried out through efficient, independent, accountable and transparent public institutions.

It is often said that Nepal is at the crossroads. It is at the junction of a paternalistic and isolated past where tradition took precedence, and a modern globalised world of the rule of law. We used to be almost immune to external influences. We are now headed full-throttle into a wider, donor-driven world. Across society, we have begun growing past the notions of "we" and "our" which used to be inherent to our traditional family structures and have graduated into the "me" and "my" compartmentalisation typical to western societies.

The dilemma today is high expectations and low, almost non-existent, delivery. Our leadership has no agenda for providing us an economic leadership suited to changing patterns of socialisation, and we cannot afford to keep anchoring ourselves to our social background. To get a sense of just how directionless we are, ask the following questions of those that lead us today, their answers will tell us all we need to know:

. How well versed are you about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats?

. Have we set our goals and objectives?

. Are we involving real stakeholders in planning and execution of decisions, or are we merely using them as uninvolved witnesses?

GIVERS AND TAKERS

In 1990, when we started rebuilding democracy, we put rules into place to elect governments in the manner most democracies do. But democratic governance-a fully transparent and accountable system-proved elusive. The system has provided more space for external players to influence decisions and decision-making. There has also been a realisation of rights, "our" rights but not that of others.

When we are efficient only if there is personal gain, then there are only "takers and givers" but no give and take. We have begun to develop specialisation for last-minute crisis management and damage control. We know there are mismatches between demand and supply, but do not pay attention to aligning the two or reducing wastage. We rely on conventional management practices.

Decisions are made at the top and passed down to those down the ladder who are expected to obey orders, even if they are not what the rules say. Even where the rules say something there is much left to the discretion of the official. And officials have excelled at using discretion, where there are personal benefits. Because everybody is made responsible for a particular job, a decision could begin with a section officer and end up with the minister's approval. This way, no one is accountable. Job responsibilities don't exist and where they do they are not defined or are just too vague.

In such a situation, hiding and cheating becomes the norm. Businesses and individuals that try to stick to the rules end up being victimised by officials with discretionary authority. Most businessmen (even ordinary law abiding citizens such as those going to the tax office to clear their motorbike and vehicle taxes) are compelled to bribe officials just to let them pay their tax.

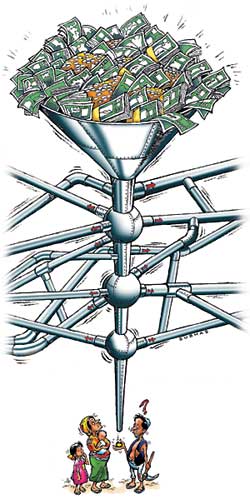

In business, bribes have become the preferred method of lubricating the machinery of the bureaucracy. Ironically, it is the under-the-table exchanges that make public employment attractive. And in the absence of clear laws and prompt implementation, graft has allowed many businesses to lower the high cost of doing business in Nepal. The bribery network stretches right up to politicians, who also need extra cash to bribe fellow politicians in the race to remain at the top of the bribery chain.

Bribery contributes to the increase in the costs that society has to pay, because it is eventually their money that is being used to grease palms. The situation begins to get out of hand where a culture of impunity prevails and there is little fear of wrongdoers getting punished.

Controlling corruption and improving governance in the public sphere would entail ending discretionary authority of officials, simplifying rules, and implementing them. Businesses can help in the process by being open and transparent, professional and by insisting on upholding rules despite short-term losses.

(Rajendra Khetan is President of Nepal Britain Chamber of Commerce and Industry.)