SADAU, THAILAND-MALAYSIA BORDER - Given the fact that what is left of Nepal's economy is being propped up by our migrant workers, you would expect them to be treated better. Remittances from Nepali workers in India, the Gulf, Malaysia and east Asia have now overtaken the country's foreign currency earnings from exports and tourism combined.

SADAU, THAILAND-MALAYSIA BORDER - Given the fact that what is left of Nepal's economy is being propped up by our migrant workers, you would expect them to be treated better. Remittances from Nepali workers in India, the Gulf, Malaysia and east Asia have now overtaken the country's foreign currency earnings from exports and tourism combined. And yet, look at the way we treat Nepalis going or returning from abroad. The ordeal begins right here in the process for acquiring a Nepali passport. They begin by filling up ineligible forms in quadruplicate, and then run around government offices to get some gazetted officer's to endorse that he knows you personally. Since HANSAs (Hindu, Aryan, Nepali Speaking Administrators) dominate Nepal's bureaucracy almost totally, this step in itself deters all other ethnicities. Those who end up with the little green book in their hands after endless rounds at the district administration office consider themselves lucky to have been thus blessed by the state.

For a Nepali Muslim from Mahottari, it's easier perhaps to reach the minister from his district, Sharat Singh Bhandari, than to find a section officer in Jaleswor to sign his application form. Since there are no local government units these days, middlemen have a field day. Touts will make things a little simpler for those who can afford their fees.

If you can get over that first hurdle, you then meet the sharks at manpower agencies that prey on the vulnerable and the desperate. Usually, the family of the worker has to sell land or take on a huge loan to be able to send abroad the son, brother or cousin or, increasingly in some parts of the country, the young woman of the family.

Despite the humiliation involved in getting out of the country, thousands of desperate Nepalis do so every year, and the numbers are growing. For the poor who have no way of getting a passport-let alone a visa, all roads lead down south, to the bustling cities of India.

Middle-class Nepalis travelling to India on pilgrimage tend to look down upon these economic migrants from back home who do the dishes at road-side eateries, without realising that it's the remittances from kanchhas like these that have prevented the collapse of the Nepali economy.

The irony is that the ones who are most proud of their Nepali identity are also the ones most willing to give it up. Perhaps they know that they can always "buy" it later whenever they need it, in the name of "non-resident" facilities. But that's a different story. Doctor and engineers migrating to Australia or America do little for our remittance economy. Our true heroes are the villagers from Myagdi toiling in the Malaysian palm plantations, or the farmers from Kavre working on Kuwaiti construction sites in 50 degree heat.

But while non-residents get to meet the prime minister when they return to Nepal on summer vacation, migrant Nepali workers returning with their meagre savings are harassed, ill-treated, and often extorted the moment they set foot on Nepali soil at the airport.

In Qatar, Thailand or Saudi Arabia, the Royal Nepal Embassies consider it beneath their dignity to help fellow-Nepali workers. The welfare of migrant workers doesn't figure on their to-do list.

The reason for such gross negligence is largely cultural: the diplomatic service tends to be HANSA-dominated, while a sizeable section of Nepali migrant workers come from humble minority backgrounds. Denied just opportunities back home, they are again deprived of attention when they are exploited or have problems in a foreign land. Could this be the reason that the Nepali Embassy in Bangkok continues to ignore the nearly three dozen Nepali inmates of Bangkwang, Klong Prem and Lard Yao prisons? Nearly all of them are janajatis.

The interest of diplomatic missions alone wouldn't be enough to reduce the sufferings of our brothers (there are still very few sisters) abroad. A diaspora commands respect only when the home country is prosperous and strong. We need to better train our workers who go overseas in search of job opportunities. And as the experiences of other "manpower-exporting" nations like the Philippines and Sri Lanka show, host countries treat guest workers differently when they realise that their unfair actions can have undesirable diplomatic repercussions.

The diaspora of Nepali professionals can also be effective in lessening the sufferings of their disadvantaged brethren. The Nepali community at the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) already visits Klong Prem once in a while, but if they were to increase the frequency, Mangal Bahadur Gurung would definitely feel less miserable about his time there. If privileged Nepalis were to campaign for the release of fellow Nepalis framed for crimes, perhaps the authorities of the host country will become more careful in the future.

The Nepali elite need not be apologetic about the first-time fliers at the back of the plane on the flight to Bangkok. International migration, caused by the push factor of misery at home and the pull factor of better prospects overseas, has a long history in Nepal and in other parts of the world. Migrants through the ages have shared a similar motivation-the determination of taking a risk in the belief that they can build their future by relocating.

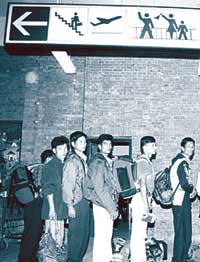

At the Sadau border post on the southern tip of Thailand, immigration officers are instructed to look carefully at the passports of all Nepalis. The Malaysian authorities often dump illegal Nepali immigrants here. Even better-placed Nepalis aren't exempt from the torturous procedure of careful scrutiny.

You may be an elite back home, but the outside world judges you by the economic state of your country.