Nepali Times asked in bold headline (#108): "When will Nepal officially request the Austrian government to return the stolen Buddha?" This rhetorical question, like the proverbial tip of the iceberg, has a far more painful subtext.

Nepali Times asked in bold headline (#108): "When will Nepal officially request the Austrian government to return the stolen Buddha?" This rhetorical question, like the proverbial tip of the iceberg, has a far more painful subtext. The obvious task is a proper criminal investigation-which, like charity, begins at home. This is not the first cultural artefact to be stolen from Nepal nor will it be the last, if the same "objective conditions" prevail, as the left lingo has it.

The element of an "inside job" is visible enough to force Nepal's family and official custodians into asking where have all our values gone? Has the market so overwhelmed our ethics that nothing except a bank account is sacred anymore? How did such a huge metallic object get past the customs and how did the Department of Archaeology seals appear in all the right places? (Of course, of course we know how: what is asked for the sake of a national catharsis is the modus operandi of who, when, how much and how high up the rot chain.)

When this story broke, one would have expected the vernacular papers and the electronic talkies to flare up with livid prose. Their deafening silence is the first symptom of the deeper pain I am referring to.

To elucidate that buried agony, let me first recount two nasty experiences, first in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Prince of Peace, and the second in Kushinagar, across the border to his place of mahanirvana. The sacrilege I witnessed still sears the memory.

The desolation of Lumbini's dug-up construction site was understandable, but what was not was the touristy bazaar atmosphere, trinket peddlers and all, that was clearly encouraged by official sponsorship. Seated on the bank of the Mayadevi pond, a Korean, or maybe Japanese, nun was desperately trying to meditate but could not: too many people, obviously picnickers, were ogling at her as they walked by with transistors blaring Bollywood obscenities.

Across the fence, a raucous cricket match was on, replete with loudspeaker commentary and more Bollywood hip-grinders. This trip to Lumbini must have been the pilgrimage of a lifetime for the nun, but the anguish on her face spoke of deep disappointment.

Across the border at Kushinagar in eastern Uttar Pradesh, ruled now and for a period then by acolytes of the neo-Buddhist father of India's constitution Ambedkar, things were not much better. It was run by the archaeological survey of the Indian government, which is fine, but the religious insensitivity hit one in the face everywhere.

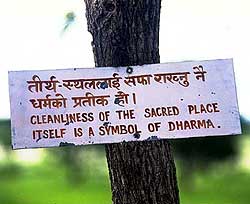

Across the border at Kushinagar in eastern Uttar Pradesh, ruled now and for a period then by acolytes of the neo-Buddhist father of India's constitution Ambedkar, things were not much better. It was run by the archaeological survey of the Indian government, which is fine, but the religious insensitivity hit one in the face everywhere. It started at the gate where a sign "by order" of the surveyor general announced that the site would be closed, off limits to all by sunset till sunrise. Why? Most Buddhists I know like to meditate at these sandhya times and at the dead of night, when there is peace and quiet. With such an order, they were forbidden to do so.

Even more outrageous, at the statue of the dying Buddha reclining on his right side another pompous "by order" notice forbade the making of offerings, ostensibly because the Buddha's statue was an ancient archaeological artefact whose value would be diminished when "polluted" by flowers, vermilion powder and sandalwood paste.

Furtively ignoring this forbidding sign, a group of Sri Lankan pilgrims were huddled in a corner chanting a prayer. One could see that half their mind was overwhelmed with spiritual emotions, while the other half was on the lookout for official reprimand. Honest, devotees were being made to feel as if they were criminals.

As if to provide a finale to this surreal scene, a khadi-clad Indian politician walked in with automatic gun-toting commandos in tow. Mercifully, he was only a curious tourist but without a shred of reverence in his face or behaviour. The irony was supreme and, as he walked out of the sanctum, Indian bhikkhus began to heckle him. Obviously, the management of the site was a matter of dispute between the local Buddhists and the authorities.

Artefacts like the stolen Dipankara and sites like Lumbini or Kushinagar belong primarily to the faithful, not the state. Only with proper sanctity will the faithful flock to these places and bring with them, as their free gift, the benefits of religious tourism. For Lumbini, if there is tourism, it should only be a secondary by-product. It cannot be the main motive promoted by the state at the expense of sanctity.

For icons, idols and masks that are part of a living culture, it is a crime to tear them out of their living context and place them in museums, or worse the guest rooms of the wealthy. There they become sad reminders of cultural cannibalism perpetrated by the morally destitute. The Austrian curator who intercepted the mask must be thanked for his sensitivity, but what of the Nepali state?

Its insensitivity is not only towards minority religions: the "Hindu" kingdom is unable to assure due sanctity even to Hindu idols or the ghats of holy rivers. This degeneration is perhaps the by-product of state sponsorship of religion. When ethical values reign supreme, religions are the essence of the much-misused phrase "civil society". When one sect receives political patronage as "state religion", that religion loses its civic function, degenerates into pompous form without ethical substance, and (in the case of Nepal's official Hinduism) discourages reforms.

The Buddhist bhikkhus of Kushinagar can at least heckle their politicians: Nepali ones, Hindu or Buddhist, would not dare. Perhaps the time has come to argue for a secular Nepali state to regain the civic role for Hinduism and save it from itself through reforms. Only then would active citizens feel confident to assert their ethics, prevent sacrilege and rescue the country's many Dipankaras from the avarice of traffickers.