Sapta Man, like hundreds of thousands of Nepali farmers, has been using hydropower for centuries. The know-how to design, build, maintain and run traditional ghattas for grinding grain is probably as old as human settlements in the Himalaya. But Sapta Man is rare among Nepali farmers because he has adapted the traditional waterwheel of his ancestors, installed more efficient paddles and ball-bearings so that with the same amount of falling water he can grind corn, wheat and millet three times more efficiently.

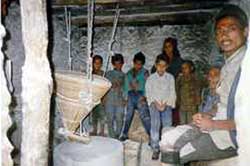

Sapta Man, like hundreds of thousands of Nepali farmers, has been using hydropower for centuries. The know-how to design, build, maintain and run traditional ghattas for grinding grain is probably as old as human settlements in the Himalaya. But Sapta Man is rare among Nepali farmers because he has adapted the traditional waterwheel of his ancestors, installed more efficient paddles and ball-bearings so that with the same amount of falling water he can grind corn, wheat and millet three times more efficiently. "The improvement in efficiency and power generation is amazing," Satya Man told us while showing us his "generation room" in Ladku village. His mill equipped with spoon-shaped metal blades in the turbine can generate up to 3 kW of power and grind as much as 15 pathis of grain in an hour-three times more efficient than his original wooden ghatta.

The traditional design is a wooden cross-flow turbine that turns a stone disc on top of a stationery disc and grinds corn or wheat that feeds into a hole on the upper stone through a vibrating metal contraption called a "bird" that can regulate the flow of grain. There are an estimated 30,000 traditional water mills still in operation all over Nepal, but these numbers are decreasing as ghatta owners near highways and in the tarai turn to diesel mills.

Efforts to improve on the traditional ghattas were started nearly 35 years ago by Swiss engineer Andreas Bachmann working with Nepali small-hydro pioneer, Akal Man Nakarmi. In a 1983 monograph, Bachmann and Nakarmi list the options for upgrading ghattas, depending on the head and flow. They put forward the design of a multi-purpose power unit (MPPU) kit that came in three easy-to-assemble modules and can be installed on the site of ghattas with minimum expense and expertise. MPPUs not just grind corn, but generate electricity, run threshing machines, looms and even belt-driven lathes. Nepali-made MPPUs have been exported to Bhutan, Ladakh and Sri Lanka.

Organisations like the Centre for Rural Technology, Nepal (CRT/N) and others are promoting similar upgrading. CRT/N which trained farmers like Sapta Man in upgrading ghattas, has declared Ladku an "Energy Village". All 26 traditional ghattas along a two km stretch of Ladku stream now run on improved turbines, and these days their high-pitch whine merge with one another as one walks down through the village.

Organisations like the Centre for Rural Technology, Nepal (CRT/N) and others are promoting similar upgrading. CRT/N which trained farmers like Sapta Man in upgrading ghattas, has declared Ladku an "Energy Village". All 26 traditional ghattas along a two km stretch of Ladku stream now run on improved turbines, and these days their high-pitch whine merge with one another as one walks down through the village. "This is probably one of most intensive uses of improved ghattas anywhere in Nepal," says CRT/N's Puspakar Lamichhane who has conducted a "ghatta census" in Kavre and found that there are 415 in 63 rivers and streams in the district. So far, 70 have been upgraded with new turbines.

One of them is Sabitri Nepali in Kunekharka who is happy with the way her family's ghatta has improved both the quality and quantity of flour that comes out of the machine. We ask her if it is true what some villagers say that the flour from the improved ghattas are not as tasty. "I don't think so," she replies. "There is no difference in taste, and I have found that the flour even has longer storage life."

One of them is Sabitri Nepali in Kunekharka who is happy with the way her family's ghatta has improved both the quality and quantity of flour that comes out of the machine. We ask her if it is true what some villagers say that the flour from the improved ghattas are not as tasty. "I don't think so," she replies. "There is no difference in taste, and I have found that the flour even has longer storage life." Sapta Man, for his part, says he is carrying out his family's traditional business. He learnt his skills from his father who did from his father. Now, Sapta Man is running his three improved ghattas as a village development enterprise with his business partners. He will couple one of them for paddy de-husking when the harvest season comes around.

This has saved a lot of time for women who usually had to queue up and spend the whole day waiting for their flour at the traditional ghatta. Others, who used to do backbreaking work at the dhikki to de-husk grain can now do it quickly and be home early.

This has saved a lot of time for women who usually had to queue up and spend the whole day waiting for their flour at the traditional ghatta. Others, who used to do backbreaking work at the dhikki to de-husk grain can now do it quickly and be home early. For his part, Sapta Man has raised his family's income level, plans to invest on bigger hydropower-driven schemes, and is looking for opportunities. And he has also volunteered his services as a consultant to other VDCs in Kavre to advise those who want to make the move to improved ghattas on the economics of it.

Improved Ghatta

Improved Ghatta The turbine runner is made of spoon-shaped blades encased in a wooden case. The chute is replaced with a metal pipe, and the shaft turns the grinding stones. The upper part with the hopper and vibrator are the same as the traditional ghatta. The power can be taken with a belt to a dynamo or a rice huller when the ghatta is not running.

Traditional Horizontal Water Mill

Traditional Horizontal Water Mill This ingenious design uses the energy of falling water channeled through a hollowed out tree-trunk falling on water wheel made of a wooden hub fitted with obliquely-set paddles and a stone pin at the bottom. A wooden shaft turns the top grinding stone as the bottom stone stays stationery. Grain in the hopper trickles into the feeding canal on the top stone through a vibrator called "bird".

(Courtesy: Mini Technology by BR Saubolle and Andreas Bachmann, 1978 Sahayogi Press and New Himalayan Water Wheels by Andreas Bachmann and Akal Man Nakarmi, 1983)

Multi-Purpose Power Unit

The unit is made of metal and comprises of three detachable segments to make it easy to carry to remote locations. The MMPU can simultaenously grind grain, generate electricity and hull rice. The increase in speed and power is due to the greater efficiency of the blade design, and the improved design of the penstock and bearings. The MPPU is versatile and can run either as a turbine only to generate electricity, or mill only or do all the work simultaneously.

"After my time, I don't know if my son will run the mill or sell it off."

I am known as Saila Baajey in the village. My registered name is Lal Bahadur Majhi. I must be between 60-65 years old. I have a family of nine. My son, daughter-in-law, my brother and his wife stay at home. I look after this ghatta [watermill].

I am known as Saila Baajey in the village. My registered name is Lal Bahadur Majhi. I must be between 60-65 years old. I have a family of nine. My son, daughter-in-law, my brother and his wife stay at home. I look after this ghatta [watermill]. This watermill was registered in 1952. As a child I enjoyed following my father here. I am now old and long for the comforts of home. This place is cold and I have no bed.

Earlier, on some days, up to 20-25 people came here. This number has gone down a lot after many motor-driven mills were installed in the area. These mills are ten times faster. Obviously they would be, a machine is a machine, after all; ours is a stone mill. And last night the water canal got damaged. One cannot do repairs at night, so water was diverted to the mill only this morning.

My father and uncle both worked in this mill; there were three shares in it then. With a son and grandson, there were more divisions, and now the mill is shared among five. We charge one pathi for every muri we grind. This is shared among five. That is enough for here, but it is not enough for the home. People at home work on the farm. There is little land. That's how it is; it's not like in the tarai here. You farm two to four terraces. You start off from one end harvesting maize but there isn't even a basketful when you get to the other end. Working on the farm is tough. It is very hard work, but there is very little crop to harvest. Running the watermill is not easy either. It is only done because it is said that a son must follow in the footsteps of the father. That's all. I lived here at the mill, now my son and grandson will stay here. What to do, there's nowhere else to go.

Everyone, not just Majhis, operates watermills. Now, if they know how, just about anybody runs them. Even Bhotes, Danwars, Chhetris and Bahuns operate them. In the old days, since Majhis lived near rivers, it seemed as if it was only their vocation. The mills are operated by whoever sets them up in these streams and rivulets.

Earnings depend on the amount of work. If we get customers, if the mill is full functional and if things are done quickly, we can earn as much as 5-6 pathis a day. Otherwise we cannot even make 1-2 pathis.

This mill grinds other grain besides maize and wheat. It grinds millet, beans and soya beans. If there are insects around, it grinds them too! It cannot husk rice, though.

As far as I can remember, there were many watermills here: up there, up there, on the other side, this side near the stream, behind the village. But most have ben abandoned. In our case, we just can't afford to leave.

Now people earn Rs 100-150 if they do some other work, whereas when you stay at the mill, you get two manas of flour [valued at about Rs 10] and the rest of the day is dry. Some have, therefore, sought permission from the department to close the mill down, and others are doing something else. Yet others are still paying taxes. We are somehow bumbling and stumbling along.

Taxes have to be paid on this water mill. During father's time it was either Rs 1 or Rs 5. now we have to pay Rs 40 annually. They do not come to collect it. Once they did not come for four or eight years and when they came after four years, we had to pay 16 twenties [Rs 320]. It is difficult to pay large sums at one time. For poor people like us, instead of such huge amounts we would be paying only Rs 40 if they came every year.

During my time, with great hardship, I managed this two manas' chore. I don't know if my son will run the mill or sell it off. There are many shares in this mill. He could decide to sell it, or he might even keep it after realising that he would lose his livelihood. After I am gone, he can do as he pleases. (From Water Wisdom, Panos Institute, South Asia, 2000.)