You know that old gag about hemlines going up with the economy? Well in Nepal, that's reversed. As the situation of the country gets bleaker, kurthas are getting shorter and shorter, as if in an attempt to add some joy to our lives, and they are also getting more and more common. After all, there are only so many permutations that the traditional six-yard Nepali fariya can take. The kurtha-suruwal strikes just the right balance between modernity and tradition.

You know that old gag about hemlines going up with the economy? Well in Nepal, that's reversed. As the situation of the country gets bleaker, kurthas are getting shorter and shorter, as if in an attempt to add some joy to our lives, and they are also getting more and more common. After all, there are only so many permutations that the traditional six-yard Nepali fariya can take. The kurtha-suruwal strikes just the right balance between modernity and tradition. The choice to wear kurtha-suruwal is more sociologically complex than might appear at first (appreciative) glance. To understand what it means to wear the more-or-less knee-length tunic with the loose, gathered trousers is a meditation on geography, religion, history, national identity, the relentless march of modernity, laziness, and the all-too-human desire for variety. "It is convenient, comfortable to wear and easy to maintain. It's versatile, and does not require skill to put on, like a sari does," says a enthusiast Aditee Maskey who works with the International Labour Organisation's Kathmandu office.

Two decades ago, few Nepalis would have believed that the kurtha-suruwal would be the subject of so much fashion discussion. Women don't anymore suddenly stop wearing them when they hit their mid-20s, or get married. Increasingly, older women are also turning to the outfit, if somewhat hesitantly, and even traditional mothers-in-law are accepting the outfit as conventionally appropriate for their daughters-in-law. The sari, that symbol of staunch Nepali Hindu womanhood, is being seen less than ever, only on ritual occasions.

The perception is that the traditional fariya is out of place in most urban settings, and the Nepali mindset is not yet ready to see most western styles gain widespread currency. As increasing numbers of women work outside the home, the kurtha-suruwal allows them to be more mobile-be less fussy when running after microbuses, sit astride motorcycles, not bother about the sari immodestly slipping down. It also reduces the workload of women at home-no more starching or unwieldy ironing in cramped apartments. Kurthas take less time and energy to be made presentable.

The perception is that the traditional fariya is out of place in most urban settings, and the Nepali mindset is not yet ready to see most western styles gain widespread currency. As increasing numbers of women work outside the home, the kurtha-suruwal allows them to be more mobile-be less fussy when running after microbuses, sit astride motorcycles, not bother about the sari immodestly slipping down. It also reduces the workload of women at home-no more starching or unwieldy ironing in cramped apartments. Kurthas take less time and energy to be made presentable. The silent concurrence on the kurtha-suruwal among people from different economic and social strata, has granted the outfit a remarkable acceptability. Women in rural communities have taken urban middle class women as their role models as far as the sari is considered, and are slowly switching their loyalties. And even if they do not wear it, the kurtha is one more kind of social code. One of the first groups of women to embrace the outfit was development workers seeking acceptability among rural communities, and yet wanting to move away from the hassles of the sari. "It puts the villagers at ease and helps them identify with the development workers-which makes establishing communication much easier," explains Jasmine Rajbhandary of Save the Children (UK), who frequently visits rural areas.

Practicality aside, the kurtha's aesthetic virtue and malleability as a fashion object has helped ensure its popularity. Man Shova Gurung, 49, wore saris all her life-she graduated from high school in a sari, obtained a college degree wearing a cotton dhoti and the sari remained her conventional 'official' wear at the Nepal Banijya Bank, where she has worked for some time now. Recently, she discovered the comfort of the kurtha-suruwal literally by accident-she sustained a fracture in her right ankle and found out that the three-piece outfit required less effort to put on.

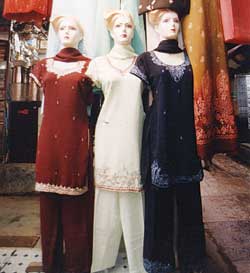

When kurtha-suruwals-known as salwar-kameez in India, and shalwar 'suits' in Pakistan-first started really catching on in Kathmandu in the late 1980s, the rage was styles copied from Pakistani teleserials. Kathmandu mothers and their daughters wanted anything that made them look like slightly flighty, yet modest, belles of the ball. (Wonder if the somewhat disturbing current rage for bleached and otherwise badly coloured hair stems from the same TV shows.) Peshan Lal, a kurtha-suruwal retailer from Bag Bazar, fondly remembers those days. "They all wanted that Pakistani touch!" he exclaims wistfully.

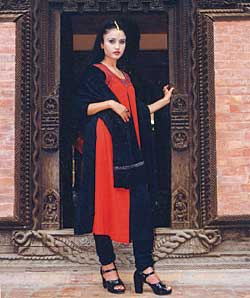

But as video faded and cable caught on, Indian fashion trends spread with the footprint of satellite channels that catered to an overwhelmingly Indian market. Peshan Lal's clientele now inquire more about designs worn by Prerna and Kusum, leading female characters in popular Sony and Star soaps, rather than those sported by the Zeenats and Afsanas of yore. And because, as we all know, TV viewers Want More Variety and Get Bored Easily, sitcom producers have realised that one way to keep their predominantly female audience hooked is by putting on a bit of a fashion show for them. (And thank god for that, who could bear those massive, hideous 1980s shoulder pads anymore.) While 2000 was the year of the floor-sweeping kurtha paired with the tight churidar, a mere two springs later, everyone is wearing super short kurthas with slits on the side up to the very top of the straight pants that go with them, sometimes without even the 'shawl' or chunni, something Zeenat-of-the-streaked-hair wouldn't dream of doing. Everyone. Whether it suits them or not. In this newspaper's considered opinion, women of medium height and a somewhat well-rounded build are the only people who look good in this style.

But as video faded and cable caught on, Indian fashion trends spread with the footprint of satellite channels that catered to an overwhelmingly Indian market. Peshan Lal's clientele now inquire more about designs worn by Prerna and Kusum, leading female characters in popular Sony and Star soaps, rather than those sported by the Zeenats and Afsanas of yore. And because, as we all know, TV viewers Want More Variety and Get Bored Easily, sitcom producers have realised that one way to keep their predominantly female audience hooked is by putting on a bit of a fashion show for them. (And thank god for that, who could bear those massive, hideous 1980s shoulder pads anymore.) While 2000 was the year of the floor-sweeping kurtha paired with the tight churidar, a mere two springs later, everyone is wearing super short kurthas with slits on the side up to the very top of the straight pants that go with them, sometimes without even the 'shawl' or chunni, something Zeenat-of-the-streaked-hair wouldn't dream of doing. Everyone. Whether it suits them or not. In this newspaper's considered opinion, women of medium height and a somewhat well-rounded build are the only people who look good in this style. All this chopping and changing has had a salubrious impact on the skills of Kathmandu's tailors, and has led to a spurt of interest in textile design and traditional Nepali textiles, too. Fabrics traditionally produced for saris and blouses are now being made into trendy kurthas. In the mid-1990s, women in Kathmandu stitched kurthas out of Indian silk and imported Japanese synthetic saris. Now, fashion designers are displaying their creativity, and using dhaka fabric, giving a fillip to an art that was stagnating.

Fashion designer Uma Chand says that her boutique in Kupondole gets about 200 orders for kurtha-suruwals each month, and that the modifications her clients request to personalise the outfit are various. Pockets for women like Rajbhandary, higher slits for those who ride two-wheelers, slimmer silhouettes for the summer and less so for the winter, better to wear a sweater under, skinny shawls, buttons on the sides, epaulettes, elastic suruwal-tops, you name it.

Let's hope kurtha lengths come down, if only as a signal that times are getting better.