We call them khaira in our language and mriga in Nepali-they eat our millet harvest and the villagers kill them in anger, but they are beautiful here," says Lhakpa Norbu Lama of Helambu pointing to a pair of spotted deer. His two Kathmandu-born grandsons giggle, shriek, and cling on to his clothes in excitement. This isn't what they expected to see in busy Jawalakhel.

We call them khaira in our language and mriga in Nepali-they eat our millet harvest and the villagers kill them in anger, but they are beautiful here," says Lhakpa Norbu Lama of Helambu pointing to a pair of spotted deer. His two Kathmandu-born grandsons giggle, shriek, and cling on to his clothes in excitement. This isn't what they expected to see in busy Jawalakhel.

Lama visits his children in Kathmandu three times a year, and his favourite activity on these trips isn't watching movies in the theatres or sunning himself on Tundikhel, picking up the gossip. It's spending a full day or two at the Central Zoo in Jawalakhel. Here on holiday last week, Lama made his pilgrimage with two grandsons and a son-in-law in tow, saying it always gives his companions a fresh appreciation for living in Kathmandu.

The Central Zoo entertains about a million visitors every year, but the high point for workers there is the annual Bhoto Jatra in May or June, when about 35,000 of the people who come to Jawalakhel from all over the Valley to view the vest of Machindranath also take in Nepal's only zoo. "During Bhoto Jatra we have a tough time controlling the crowd, some years we even run out of tickets," says Chiri Maharjan, a zoo guard. "Nepalis are essentially nature-loving people-they go wild with excitement when they come here," he smiles. No surprise, for right in the heart of downtown Lalitpur, visitors are confronted with six hectares housing over 800 animals of 126 species-30 mammal varieties, 66 birds, eight reptiles and 22 fish species. There are a number of exotic species too, the most recent additions being a pair of siamang brought in from Malaysia, ostrich from Australia and a hippopotamus from Thailand.  This is a much-neglected institution, but don't blame the zookeepers. Most of them are committed beyond the call of mere duty. Krishna Maharjan has worked at the zoo for 18 long years, and has taken responsibility for the hippos. "People are just awe-struck at the sight of them. Children love to stare at them-some compare the animals with pigs, others think they look like rhinos without their rough outer hard skins," he laughs. Maharjan has seen how close the bond between human and beast can be. "These animals have become my family. I feel sad and worried if they get ill." More than that, Maharjan can tell whether his charges are happy, depressed or plain

This is a much-neglected institution, but don't blame the zookeepers. Most of them are committed beyond the call of mere duty. Krishna Maharjan has worked at the zoo for 18 long years, and has taken responsibility for the hippos. "People are just awe-struck at the sight of them. Children love to stare at them-some compare the animals with pigs, others think they look like rhinos without their rough outer hard skins," he laughs. Maharjan has seen how close the bond between human and beast can be. "These animals have become my family. I feel sad and worried if they get ill." More than that, Maharjan can tell whether his charges are happy, depressed or plain

old bored.

The Central Zoo was established in 1932 by Prime Minister Juddha Sumshere Rana as a private collection of wild animals. Life-size bronze statues of his mother and sister-in-law still look down on visitors to the zoo. With the political and social changes that followed 1951, when the amassed wealth of the Rana prime ministers was nationalised and a number of properties turned into public utilities, the ownership finally came to the government in 1956. The management of the zoo has changed hands a few times, but it remains fundamentally what its creator envisaged-a collection of rare wild animals, but with one important amendment to his vision-the right of the public to enter the area.  The public could enter, but for a long time there was little reason for most people to do so. Mainly because the government lacked the expertise and the motivation to manage a zoo and develop it into an educational institution, it fell into disrepair, and the cursorily tended to animals and their surroundings were far from attractive. Many Kathmanduties had even forgotten about the existence of the zoo by 1995, when the management of it was handed over to the King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation (KMTNC). The KMTNC was given the responsibility for 30 years, and the government agreed to stay on as a facilitator and monitor the zoo activities.

The public could enter, but for a long time there was little reason for most people to do so. Mainly because the government lacked the expertise and the motivation to manage a zoo and develop it into an educational institution, it fell into disrepair, and the cursorily tended to animals and their surroundings were far from attractive. Many Kathmanduties had even forgotten about the existence of the zoo by 1995, when the management of it was handed over to the King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation (KMTNC). The KMTNC was given the responsibility for 30 years, and the government agreed to stay on as a facilitator and monitor the zoo activities.

Zookeepers say the central government has virtually abdicated this role. For the first five years after the KMTNC stepped in, the government provided the zoo grants to cover its running costs. "But after it stopped the grants, government authorities hardly even visit the zoo anymore," says Chief Administration Officer Achyut Raj Pant.

Things at the zoo are a lot better, though. For the first time last fiscal year it earned enough money through ticket sales and renting out animals as well as space to raise the Rs 20 million it needs to cover its annual costs. It seems like a lot, but after the salaries of 72 employees, animal and bird feed, small-scale renovations and constructions and administrative costs, there's nothing left to pamper the beasts.

Some of the animals do need pampering. The Central Zoo exhibits 13 out of 38 endangered animal species of Nepal, and has been particularly successful in breeding blackbuck-some eight years ago it released 25 of the deer in the wild. The program wasn't too successful, but the keepers have learnt from their mistakes and are considering the release of a second batch of 25. "This time we are taking serious precautions," says director RK Shrestha. An animal exchange program was also initiated after the KMTNC took over the management-the recent rare additions are courtesy zoos abroad.  Animal security is the other major concern of the zoo management, and an area where it could really use some more cash. The six hectares are guarded by just 10 untrained men, and two low-ranking policemen. This is just not enough to repel an attack like the one in 1999, when poachers broke into the zoo, killed two rare one-horned rhinos, and mutilated them, then escaping with the precious horns. Zoning laws are such that there is no buffer patrol zone on the perimeter of the zoo, instead there are private houses whose residents couldn't care less what happened to the animals.

Animal security is the other major concern of the zoo management, and an area where it could really use some more cash. The six hectares are guarded by just 10 untrained men, and two low-ranking policemen. This is just not enough to repel an attack like the one in 1999, when poachers broke into the zoo, killed two rare one-horned rhinos, and mutilated them, then escaping with the precious horns. Zoning laws are such that there is no buffer patrol zone on the perimeter of the zoo, instead there are private houses whose residents couldn't care less what happened to the animals.

To address these administrative and financial concerns, the KMTNC has developed master plan for the development and modernisation of the zoo. The major thrusts of the plan are physical design development, animal collection and management and conservation activities. The plan for the animal collection and conservation activities has in-built fundraising components, now the challenge is finding money for the physical design development estimated to cost Rs 600 million. "Informal talks have been held, but nothing concrete has happened yet. We are still looking for donors and collaborators," says Shrestha.

Keeping the zoo's success story afloat

In 1997, the zoo began a project called Friends of the Zoo under its conservation education program, targeting schoolchildren and their parents. Already, the FoZ is acclaimed as one of the best undertakings of its kind in Asian zoos. For an annual fee of Rs 150, schoolchildren can avail of conservation educational activities, tours to the wild, discounts in various stores in the Valley and free entrance in the zoo, and also participate in tending to and feeding the animals. FoZ presently has over 9,000 members from about 75 schools in Kathmandu Valley. "Children between the ages of 11 and 14 are more keen on our activities; the older ones are already overburdened with preparing for SLC exams," explains Geetha Shrestha, chief of FoZ.

Most of the members are students of private schools, in large part because the Rs 150 is simply too much for children in government schools to pay. Bhawani Raman Subedi, a teacher at the Bhaktapur Adarsha School, who was taking his 54 students around, was disappointed, but not too much. "Our students are not members because their parents cannot spare the cash. But we bring them here and other nearby animal reserves for their project work in zoology and biology," he said.

FoZ would like to subsidise membership fees for government students, but simply cannot spare any of its Rs 1.7 million budget. The fees it collects only total Rs 300,000-400,00. But, says FoZ's Shrestha, they are considering the request of the government schools for group memberships and have started identifying contact people in schools so the children can have more opportunities to participate with their more privileged peers.

Another program, under the zoo animal welfare scheme, is getting sponsors for animals. The cost to partially sponsor the feed for an animal ranges between $170 and $3340 annually, depending on the animals and the size of their enclosure. This programme was introduced to lighten the zoo administration's Rs 4 million annual feed bill.

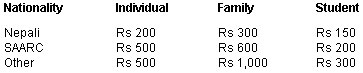

Become a member of Friends of the Zoo