It is sometimes said that everyone in a Nepali village knows who the Maoists are, except the soldiers. To John Richardson, that is no surprise. It is a pattern he has seen around the world.

It is sometimes said that everyone in a Nepali village knows who the Maoists are, except the soldiers. To John Richardson, that is no surprise. It is a pattern he has seen around the world. One of his arguments is that a major failure of policy-makers and donors is to ignore two key but unfashionable factors-community police and young men. Governments tend to pump money into armies that prop up a small nation's pride in peacetime, but can never address a 21st century crisis.

Meanwhile, donors ignore the needs of young men, who are most likely to turn their thwarted energies into violence. When ill-funded and dispirited police fail to stem a movement fueled by angry young men, armies are predictably called in, and just as predictably fail.

Richardson is a Sri Lanka specialist who has devoted over two decades to studying guerrilla conflict and trying to pinpoint the common factors in struggles that drag on until both sides come to a "hurting stalemate" and are weary enough to talk.

Guerrilla wars are rarely won by either insurgents or governments, notes Richardson, a former military man who teaches at the American University's School of International Service here, and who recently visited Nepal.

Insurgents around the world tend to be better armed, better motivated and even better trained than soldiers. They are often self-sustaining, through extortion, robbery, smuggling, drug running, and in the case of some, such as the Tamil Tigers, through the deep pockets of the diaspora. Yet even the Tigers, whom he calls "perhaps the most resilient and best-armed rebel army in the world", have failed to achieve their goals through bloodshed.

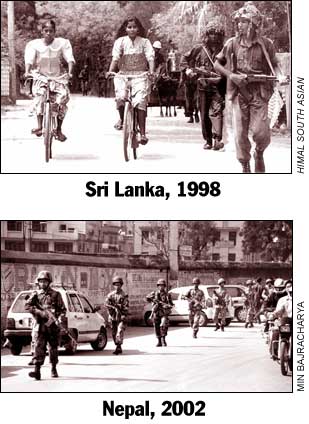

Meanwhile, armies aren't equipped-and perhaps never can be-to fight effectively against their own people, Richardson adds. Their training prepares soldiers to fight an easily identified stranger, yet in modern times, virtually the only time a small country's army will be used is to fight its own population.

A small, impoverished country attacked by a major power would win or lose based on its ability to find allies, not based on its own army, he argues. Costa Rica is one of the few countries without an army, shows that it is possible to have a nation without a military, and this could be a model for Nepal and Sri Lanka.

"The truth is, Nepal doesn't need an army at all," he says provocatively. "It may need a few people to guard the palace and for ceremonial duties, but what is the point of an army? To fight India and China? The same is true in Sri Lanka. This doesn't mean there is no need for security. But in the budget process, the army gets preferential treatment over police."

And that, he says, is the mistake. If the goal is a secure life for the country's people, that would be better maintained by a professional police force that lives in the community, knows its dynamics, and can identify a threat as it begins. "In Sri Lanka, and even more in Nepal, there has been a tendency to neglect the police force," he notes.

And that, he says, is the mistake. If the goal is a secure life for the country's people, that would be better maintained by a professional police force that lives in the community, knows its dynamics, and can identify a threat as it begins. "In Sri Lanka, and even more in Nepal, there has been a tendency to neglect the police force," he notes. Police in both countries have been underpaid, have bad public relations, are poorly trained, poorly armed, politicised and placed in a position where bribery and corruption are tempting alternatives. So when the time comes to call them out to deal with a nascent movement, they don't get the support of the community. And they're likely to beat up on people who are opposed to the government, but not really militants, and create circumstances where they are unwittingly serving as recruiting agents.

An unpopular police force is paired with what, in colonial terms, can be called the "outstation mentality" in which civil servants and development workers shy from living outside the capital. "People will go, but everybody is doing their best to stay in the capital," he notes.

"People in the outstations are under-funded, and may even be sent out there as punishment. Then, when trouble comes, they're called on to lay their lives on the line."

It doesn't work, and in time, the army is called to maintain security. But if security is defined as the right of ordinary people to live in safety, that means they're doing the job of police, he says.

And who are they fighting? In major part, disenchanted young men. Yet donors seem blind to this vast, hurting group until it's too late. It is only when enough of them join an insurgency that donor-funded projects scurry away, leaving years of development in shambles.

Add that to a lack of urgency within governments, and a refusal on both sides to see that total victory is impossible, and the stage is set for the sort of protracted, winner-less conflicts seen in Sri Lanka. The island nation was wracked by two insurgencies: one a separatist civil war in the north waged by the Tamil Tigers, and the other the Maoist JVP uprising in the south. The Sri Lankan army and the Tamil Tigers reached a stalemate. Each side realised it couldn't win, and both were ready to try something else. What also helped was the post-11 September scenario, and the threat of being put on the terrorist list by the United States, Britain, Canada and Australia endangered the diaspora funding, which in turn forced the Tigers to look for an alternative. The Tigers are currently engaged in peace talks with the government, and the ceasefire in the northeast has held for a year.

The JVP uprising was quashed after top leaders were rounded up and killed after an intelligence breakthrough in 1990. The JVP is now the third largest party in parliament, with political clout disproportionate to its membership because it controls the swing votes.

Richardson is currently completing a book on democratisation in South Asia and the political economy of the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. His recent research and writing has focussed on the prevention, management and resolution of political conflicts in developing countries.

Is it really necessary for Nepal to go through what Sri Lanka went through for 20 years with 80,000 deaths? The war can be much more destructive in Nepal because of the terrain, and also because it is already a much poorer country than Sri Lanka. A recent visit to Kathmandu did not leave Richardson encouraged. The missing element, he told us, was a sense of urgency. And without it, there is little to keep the violence from stretching on for years-or even decades.