The United Nations representative in Nepal has said that the UN would be willing to act as a mediator if both conflict parties are willing to talk. The US Ambassador to Nepal said that the Maoists must be brought back to the table (NT, #117). Both could be the first signs that international mediation may actually allow us to settle the conflict just as it was done in El Salvador 10 years ago.

But it requires a government that has the political and moral courage to boldly push ahead with initiatives that will be acceptable to both parties as well as the international community.

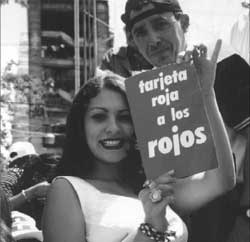

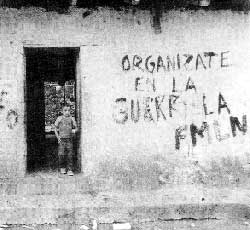

"Red card to the reds", the people said in El Salvador, ignoring grafitti that exhorted them to organise fort the FMLN instead.

When the government of El Salvador and the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) signed a peace accord on 16 January 1992 to end the twelve-year insurgency, both sides claimed victory. The FMLN leader Joaquin Villalobos declared that it was the first revolution won through negotiations. The talks lasted eight years and the tenacious bargaining was greatly influenced by external actors. Throughout all this, the government of El Salvador had displayed a remarkable unity and patience with an adversary that either constantly added negotiating demands or deliberately stalled the progress of negotiations.

The FMLN began in January 1981 as a loose Cuban-supported confederation of insurgent factions whose goal was to create a revolution similar to which had occurred in neighbouring Nicaragua in July 1979. In one violent decade this insurgency had cost the lives of 75,000 people and wreaked destruction worth $2 billion to the Salvadoran economic structure.

After winning the presidential elections of 1984, Jose Napoleon Duarte of the Christian Democratic Party opened the first of many attempts at negotiations with the FMLN, which were initially spurned. With the presidential elections slated for March 1989, the FMLN suddenly sent a peace proposal, but this was a ruse. The guerrillas were secretly preparing a big offensive, which they launched on 11 November 1989. In a remarkable display of raw, brutal power and daring, the FMLN invaded populated neighbourhoods of San Salvador and held them for a couple of weeks, at great cost.

Despite the nation-wide guerrilla terrorist campaign to intimidate and disrupt the elections, the turnout and the support for the FMLN's political allies sent a clear signal that society had rejected those who endorsed the path of violence. The failure of the November offensive finally forced the FMLN to agree to negotiations with the government under United Nations auspices.

Talks began on 4 April 1990 in Geneva under the auspices of the Secretary General of the UN. The ice had been broken. The initial objective of this accord was "to terminate the armed conflict by political means in the shortest time, to promote democratisation of the country, to guarantee the unrestricted respect of human rights and to reunify Salvadoran society."

In July 1990, the government and the FMLN signed an agreement on human rights that included establishment of a United Nations verification mission. However, after this meeting, the FMLN stalled progress in negotiations as they awaited the outcome of the debate in the United States Congress on military assistance to El Salvador. They were still hoping that a halt in this aid would enhance the chances of a military victory.

In April 1991, when the two sides met again in Mexico City they agreed on constitutional reforms concerning the armed forces, the judicial system and human rights, and the electoral system. In September the Salvadoran Congress ratified these constitutional amendments. Yet another agreement was signed to permit the FMLN guerrillas to incorporate into a new police unit under the civilian Ministry of Interior rather than the Ministry of Defence, a promise that the guerrillas demanded as a means of guaranteeing their personal safety.

After personal intervention of the outgoing Secretary General of the UN Javier Perez de Cuellar and under strong pressure from the governments of the US and other Latin American governments, the two sides met in New York in December and agreed on the technical-military aspects of a ceasefire.

This included the end of the military structure of the FMLN, and the re-incorporation of its members into the civilian, political and institutional life of the country. The final peace accord was signed on 16 January 1992. Peace was achieved in a manner in which all actors could claim success. The government was able to prevent the takeover by the FMLN and at the same time, established a functioning democracy, carried out basic structural reforms, attained peace and did so within the framework of the constitution.

The FMLN could claim that their revolution had prevented the return of oligarchic governments and their military strength had enabled them to negotiate for greater societal reforms and structural changes of the government. Throughout the insurgency, the unity displayed by the ruling party, the loyal support of the opposition and the cooperation of all other national actors remained crucial for success.

Insurgents increase the level of violence either when they feel that their political base is narrowing both externally and internally or when they desire to strengthen their negotiating position vis-?-vis the government. The government should always attempt to talk formally and informally with the insurgents and their political allies whenever an opportunity presents itself.

Whereas the guerrillas will remain adamant in their negotiating demands as long as possible, the government must be able to display the ability to survive politically and militarily to thwart the ultimate offensive by the insurgents or a mass uprising by a disgruntled population. The government must have the vision and the capability to plan for preventing radicals of the right and left who may try to derail the peace process through assassinations.

The crucial factor in El Salvador was the trust both parties vested in the mediation role of the United Nations. The Secretary General was proactive, and was able to get both parties to accept him as the sole arbitrator. The influence of the regional countries in applying pressure on both parties to negotiate, and the assurance of economic aid by the United States were other factors.

Each insurgency requires specific and surgically precise tools to defeat. A display of physical and moral strength, honesty, flexibility and mutual trust backed by corresponding actions by both parties are needed to create a conducive environment for negotiations.

(Hitman Thapa is the pseudonym of a Nepali military historian.)

Lessons for Nepal from El Salvador

. Both sides have to realise that violence is a dead-end

. There has to be political and moral will

. All democratic forces must be united

. Both sides need flexibility and a spirit of compromise

. Outside powers should not interfere and stoke tensions

. Mediator must be trusted, discrete and sole arbitrator

. Government must have credible military deterrence

. Split between hardline and moderate rebels must be prevented

. Government must deliver social reform and development

. Both parties must avoid playing to the gallery via media