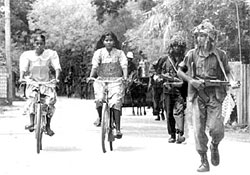

The rise, fall and conversion of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) Sri Lanka's Marxist radicals of the 1970s and 1980s turned Buddhist-nationalist parliamentarians has parallels with Nepal's Maoists.

The rise, fall and conversion of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) Sri Lanka's Marxist radicals of the 1970s and 1980s turned Buddhist-nationalist parliamentarians has parallels with Nepal's Maoists. The JVP, too, was into a class war but unlike the Maobadi, preferred not to fight in the bush. They had some active support among the Lankan urban elite but Nepal's rebels are mostly a rural phenomenon having more in common with the insurgencies in Bihar, Jharkhand and Andhra.

The state's response to the JVP was to crush it with the same brutality shown by the rebels themselves, killing five of their senior-most leaders including Rohana Wijeweera. The nationalism and anti-Indianism of the JVP is akin to the chauvinism of Nepal's Maoists, which ironically take after the nationalism created by King Mahendra to buttress his autocratic Panchayat system.

However, the separatist Tamil war in Sri Lanka is quite different from our insurgency. The only pointers Nepal may take is from the ceasefire and rapprochement that is underway there. (See also, Editorial, 'From warfare to welfare', #253)

In Sri Lanka, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) led an identity-led war, which makes their battle that much more heartfelt, longlasting and angry. This is why you had suicide bombers in Sri Lanka but not (yet) in Nepal. The Maoists, though they have tried to exploit ethnic discontent, propose a class war. The LTTE has total command of the area that it would like to liberate and are a kind of external enemy that a national army is groomed to battle.

In Nepal, the Maoists have the run of the countryside because they are filling a vacuum evacuated by the government. But they do not control any part of the country in the sense that they can prevent the state security apparatus from entering. All 75 district headquarters remain under government control and the Maoists at best are able to attack during the night and torch some buildings and create some mayhem before they evacuate.

The LTTE wants just a part of Sri Lanka, but the Maoists, in theory, want the whole of Nepal. Even though the Maoists have seen rapid spread in the rural hinterland, the fact is that the Maoists do not have the ability to combat the Royal Nepali Army in conventional warfare, which should give pause to those Kathmandu-based ambassadors who panic at the prospect of a Maoist takeover of Kathmandu Valley and the state. This is view of Maobadi takeover is one the Kathmandu regime would like to propagate, and the Maoists would welcome such an exaggerated view of their capabilities.

The LTTE wants just a part of Sri Lanka, but the Maoists, in theory, want the whole of Nepal. Even though the Maoists have seen rapid spread in the rural hinterland, the fact is that the Maoists do not have the ability to combat the Royal Nepali Army in conventional warfare, which should give pause to those Kathmandu-based ambassadors who panic at the prospect of a Maoist takeover of Kathmandu Valley and the state. This is view of Maobadi takeover is one the Kathmandu regime would like to propagate, and the Maoists would welcome such an exaggerated view of their capabilities. Even in the worst days of the civil war in Sri Lanka, the army was very much under the control of the parliamentary system, whether the prime minister or lately the executive president. In Nepal, while the 1990 Constitution places the army within civilian control the reality is that the royal palace and the king as 'supreme commander-in-chief' call the shots. The complete capture of state power by the palace on 1 February was carried out with the help of the military, which was already deployed throughout to battle the Maoists.

Today, as a matter of course, military officers have become de facto administrators, with the civilian and police administration deferring to them. This, unlike in Sri Lanka, takes the country in the direction of army-ruled Pakistan, a trend which worries those who had hoped to see the RNA evolve into a professional fighting force.

The full economic cost of the Sri Lankan civil war, including military expenditure, damage of physical assets, tourism and commercial losses, and expenditure on displaced persons, is estimated at $4.7 billion. The total including the cost of foregone economic possibilities comes to $14 billion. No comparative count is available for Nepal's nearly ten years of insurgency, and when we finally have the tabulated figure it will no doubt be horrendous. And no kind of methodology could tabulate the cumulative pain of the rural populace over the years.

Even in the worst days of the Lankan civil war, the democratic state held ground. Today, Executive President Chandrika Kumaratunga, opposition leader Ranil Wickremasinghe, and even Prabhakaran of the LTTE, are displaying forbearance and sagacity. Which is why the ceasefire holds even though the peace process is stuck. Sagacity is what the Nepali people also need from those who would rule over them.