On the streets of Kabul below hulks of bombed out houses, there are boys playing. Not a single girl. Where are the girls? "The girls only play inside the house," explains my colleague, Regina.

On the streets of Kabul below hulks of bombed out houses, there are boys playing. Not a single girl. Where are the girls? "The girls only play inside the house," explains my colleague, Regina. In the market, there are more women than usual, but they are covered from head-to-toe in burqas. Some things change slowly, even if the Taliban are gone. Regina, who doesn't wear a burqa, tries to explain: "In our culture we have to wear it."

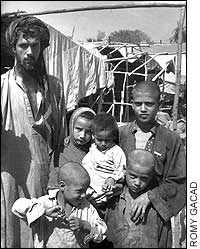

The Afghans are happy they have been liberated from the Taliban, and their fanatic interpretation of Islam which banned music, and girls from going to school. And right there on the streets my thoughts turn to Nepal, where neither boys nor girls can go to school because of threats by the Maoists. What will our future be? Is it all going to end up like these cratered streets and buildings hollowed out by bombs and rockets from two decades of war? And when our own country is completely destroyed, will we also emerge from it like the Afghans have to realise how utterly senseless it all was?

Our children are our future leaders, our lawyers, our doctors, nurses and social activists. They are our future journalists. The Taliban did not want girls to go to school because, they said, their scriptures said so. Is that any different from what our own fundamentalist Maoists are doing? Marx, Lenin, and especially Mao himself would never have condoned such a wanton assault on schools, and the future of children. Even in the worst years of war in Sri Lanka, both the Tamil Tigers and the army had a ceasefire at exam time.

We have to ask: who is most hurt by this nationwide attack on schools? Not the rich kids, whose parents have already pulled them out and sent off to boarding schools in India. No, it is the rural folks who have saved all to be able to afford an education for their children and have invested in their future. If the Maoists really want to reform the school system, there are do-able things to address the government school system. This leads me to conclude: maybe the closure of schools is not about reforming education at all, but about getting faster to Year Zero.

I call home from Afghanistan, and my daughter answers the phone. Why aren't you in school, I ask. "It's a bandh," she answers on the line, and I can sense she is secretly glad not to have to go to school on a cold morning.

Walking the ruined streets of Kabul, past the wreckage of an armoured personnel carrier and a brick wall scarred by bullet holes, I watch a girl about the same age as my daughter carrying water home in a large jug. And I get a sudden glimpse of our own future.