Seated in the pleasant common room of the Blue Diamond Society in Lazimpat, Pant and his colleagues voice their frustrations and fears at a society that considers homosexuals freaks. They talk about abuse by the police, rape, torture, blackmail, family apathy and denial, and the individual fear of coming out of the closet.

"When I tried to register Blue Diamond Society with the Social Welfare Council as an NGO working for the health of homosexuals, I was advised it could lead to legal and social complications," recalls Pant who finally opted for the less-loaded term "male sexual health".

Sunil's centre along with groups like Richmond Foundation, Freedom Centre and Life giving and Life saving Society (LALS) all contributed to the UNICEF film, Kathmandu: Untold Stories which was released last month. Filmmakers Subina Shrestha and Alex Gabbay's 26-minute documentary explores the dark underbelly of Kathmandu society.

"The film is not really an AIDS awareness film in the proper sense," says Shrestha. "It's more about young people in the city who live lives their families know nothing of or don't want to know about. As they tell their stories, it becomes clear how complicated everything is. And how young people are forced into dangerous situations that often expose them to HIV/AIDS."

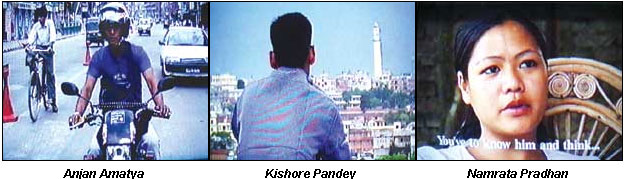

Shrestha and Gabbay interviewed friends, friends-of-friends and, with the help of various organisations working in HIV/AIDS, met people like 27-year-old Kishore Pandey, a government employee.

Pandey is a member of Blue Diamond Society, is happily married, loves his wife and has two children. But he has a "third life". He asks: "What do I lack? Why shouldn't I have married? Nobody in my family can tell that I am gay and I could not tell them. I didn't even know myself. I came to know about it much later."

But unlike the majority of MSMs who visit the society's counseling centre and drop-in clinic, Kishore is aware of the dangers of unsafe sex and the vulnerability of MSMs to HIV/AIDS. "Gays do test for HIV. We enjoy having sex and we have to be extra careful that we don't harm others."

People on camera insist that society must listen, talk and get out of denial. "The most ironic and hypocritical thing about our society is that families will get their sons or brothers married, knowing that they are HIV positive. They still want to save face, and he wants to have fun. He can neither say yes nor no. He'll give into parental pressures and get married," says Rajesh Chettri, a 23-year-old student who became a drug addict after his parents died. "I was all alone. I could not deal with myself. I guess I took drugs because I felt isolated from my family," says Chettri in the film.

AIDS is going to be the single biggest killer of Nepalis in the 15-49 age bracket in the coming decade. Commercial sex and injecting drug use are combining to spread the epidemic to the general population, which means that anyone, not just the vulnerable groups, are at risk. "But as long as the problem doesn't stare them directly in the face, it's difficult to take seriously," says Shrestha. The film was shot in Kathmandu so policy-makers in the capital would take notice. "If officials saw a film about the HIV problem in Accham or Doti, they would probably not identify with it," she adds.

At 19, Namrata Pradhan is comfortable with herself and her sexuality. She speaks frankly about love, sex and relationships and how it's wise to know someone well before progressing into a sexual relationship. She says, "But the problem starts when the boy's attitude is to have fun. The girl won't know about the boys-who he is, his past, how many girls, if he has practiced safe sex, used condoms or if he has AIDS. Girls don't know these things and then they could have problems."

Girls like Nisha, a dancer in one of Kathmandu's restaurants, arrived in Kathmandu with big dreams. The few happy moments that she enjoys is when she meets her friends in the evenings. Many of the girls, including a few of her friends, have become sex workers. "Girls end up going in for money and get trapped," says Nisha who dances till 10PM and goes home to sleep.

"Just about everyone in Kathmandu has an untold story," says Anjan Amatya, who tested HIV positive three years ago. He now works at the self-help group, LALS. "HIV is not just about a virus. It's about our relationships and about facing up to our problems. It's about you and me," Amatya said to viewers at the premier of the film in December. "Denial is dangerous, it's not just enough to fulfill the material needs and comforts of children. They need someone to love them, understand them, someone to talk to and share their problems with."

That is, in essence, what we need to do-talk, share and eventually heal.

Coming out...safely

On 1 February, approximately 70 participants from urban areas around Nepal will gather in Kathmandu for the first national consultation meeting for male reproductive and sexual health. "The rationale for the meeting is to explore the profound implications that male-to-male sexual behaviour may have for the STI/HIV-AIDS epidemic in Nepal," says organiser Sunil B Pant of the Blue Diamond Society. The society is a community-based sexual health service for local networks of males having sex with males (MSMs) and Male Sex Workers (MSWs) in Nepal. It has a drop-in centre, outreach clinic and clinical services focusing on STIs. The meeting will highlight issues like appropriate strategies and models to address not only the sexual health of MSMs and their partners in a culturally appropriate manner. Human rights concerns regarding MSMs, questions of stigmatisation and discrimination and the socio-cultural-religious contexts of male sexual behaviour in marriage and family will also be discussed.

Blue Diamond Society Hotline: 443350